The premieres continued on the first Friday of the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival, including new films starring Saoirse Ronan, Margot Robbie, Steve Buscemi, Jason Sudeikis, Jessica Chastain, Jake Gyllenhaal, and many more. We’ll get to the boys later in another dispatch, but I had a chance to see the Ronan vehicle and Robbie’s transformative performance today, and can report on a pair of other “smaller” films that may not have gotten the same red-carpet attention.

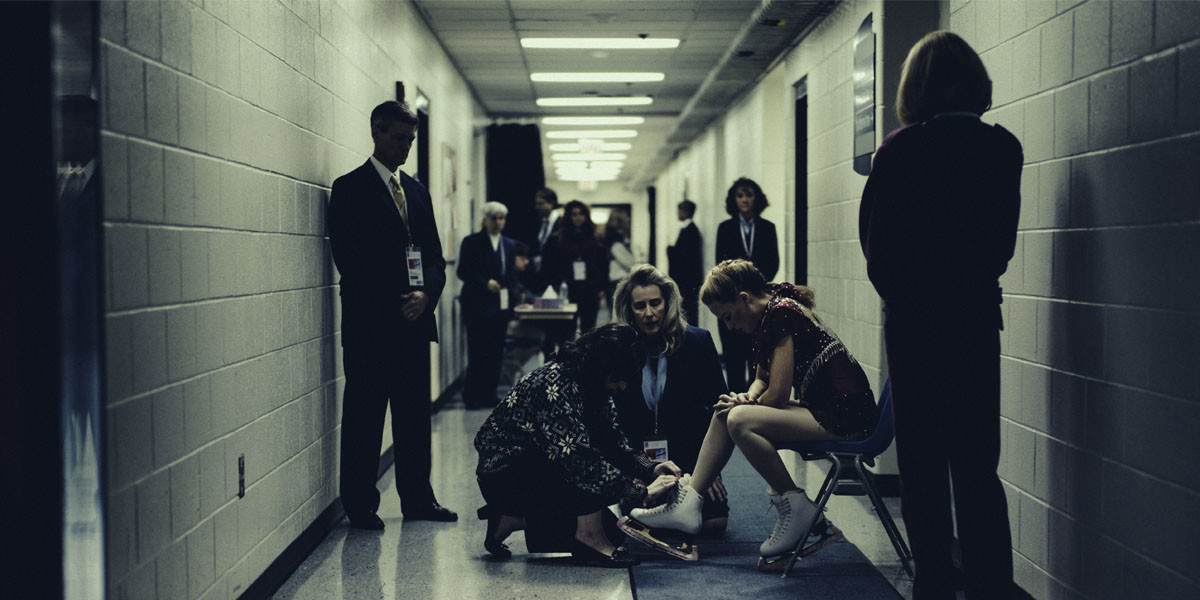

Let’s start with the biggest surprise of TIFF 2017 so far, Craig Gillespie’s razor-sharp “I, Tonya,” the dark comedy approach to the story of Tonya Harding that you had no idea you needed as badly as you do. Writer Steven Rogers and the director of “Lars and the Real Girl” approach a story you think you know as if it’s the fourth season of “Fargo,” finding black veins of hilarity, absurdity, and violence in the story of ice skating’s most controversial figure. It would be an understatement to say that Gillespie’s film does not take the typical biopic approach. It is not an “explainer film”—one of those movies that tries to recast a controversial figure in a new light. It is something altogether strange and original, and it’s a film people are going to be talking about.

From the beginning, the tone of “I, Tonya” is unexpected because there was enough darkness in Tonya Harding’s life for an entirely different approach. As captured here—and the film make it clear in clever ways that truth is fluid and even the interviews used to make this film were contradictory—Harding had to fight her entire life. Her mother, played here with horrific perfection by Allison Janney, one of cinema’s best hurlers of profanity, was just awful. She chain-smoked, physically abused Tonya, and convinced herself that it was her pushing of her daughter that made her a star. As she says late in the film, her own mother did nothing and she still hated her. At least Tonya was a star athlete.

Harding went from one abusive relationship to another, ending up with the unforgettably mustachioed Jeff Gillooly, played with a dangerous blend of idiocy and rage by Sebastian Stan. This take on Gillooly is as one of those people who are so blandly stupid that violence just becomes a part of their life because they can’t think of any other way to fix their problems. Jeff and Tonya would scream and fight and hit and sometimes shoot, and she took that anger and channeled it into something at which she was undeniably great, ice skating. Gillespie and cinematographer Nicolas Karakatsanis do a phenomenal job of capturing the flow and excitement of the sport, but the whole film sparkles in terms of visual compositions with a camera that almost always feels like it’s moving, skating in and out of domestic scenes as well as ones on the ice, but never to a distracting degree.

The centerpiece of “I, Tonya,” and what people will really be talking about, is the stunning work from Robbie, the best of her career to date—yes, I know, she’s great in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” but this is challenging on a different level. Her take on Harding is much more than just a physical transformation—she presents Harding not as a tabloid subject or a sob story but a completely three-dimensional person, someone who knew the world was unfair at a very early age and had to fight against that at every turn. Robbie is alternately defiant and hysterical, but she never takes the easy way out, which would have been to turn this take on Tonya into a parody or a tragedy. She contains elements of both. She’s alternately defiant and miserable. It’s a physically and emotionally demanding performance, and Robbie doesn’t take a single false step. She does something even most traditional biopics fail to do—she tells us her side of the story in a way that feels heartfelt and genuine. Everyone here is great—I didn’t even mention the always-fantastic Julianne Nicholson and Bobby Cannavale—but it’s Robbie’s movie. And she nails the triple axel.

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” With this great opening line, Ian McEwan’s novella “On Chesil Beach” sets its stage perfectly. Set in 1962, this short but brilliant book examines a time of sexual repression, and how that was coming to an end, although perhaps not quite quickly enough for his protagonists, the newlyweds Florence and Edward. As played in the film adaptation by Dominic Cooke (written by McEwan), these two are uncommonly in love with one another but have never made love, and the typically beautiful consummation on their wedding night—well, let’s just say it doesn’t go as planned.

The always-phenomenal Ronan plays Florence as a perfectionist but not in the cold, detached manner a lesser actress would have taken the material. The film version of Flo is more gregarious than I expected (I was a big fan of the book FYI), but the interpretation works. Even in the book, Florence is a woman who is stridently confident in the right situation, willing to defy her strict parents and date a boy of a lower class, and willing to go to meetings to Ban the Bomb. She’s just not interested in sex. A passage in the film, taken loyally from the book, in which she reads about something as disturbing as penetration is fantastically captured.

While Ronan is predictably strong, the breakthrough here is “Dunkirk”’s Billy Howle as Edward. Howle’s performance will rank with the best of TIFF. He perfectly captures the blend of naivete and confidence within this young man, one who recognizes that he’s on the cusp of a cultural revolution, and just happens to still be in a time when men have to get married if they want to get laid. Howle deeply understands this character—his relationship to his brain-damaged mother, his unabashed romanticism and love for Florence, and his eventual, life-changing anger.

What holds back “On Chesil Beach” from the greatness of the book is relatively predictable in that the source is practically a short story and much of it takes place in flashback/memory. In the book, McEwan can telegraph the sense that we aren’t really leaving this pair on their wedding night as much as filling in the gaps in a way that makes the baggage they bring to their bed clearer. The film, on the other hand, feels more traditional in that we are always leaving the beach, going through long scenes about their courtship and learning about their characters in ways that feel more cinematically clichéd. It’s an arguably unavoidable byproduct, although the over-use of score and close-up in the final act in an effort to increase melodrama probably wasn’t. Overall, this is a solid drama made from a stellar book, but if you see it even just for the two performances, you won’t be disappointed.

Stephen McCallum’s “1%” could somewhat accurately be called “An Australian Sons of Anarchy,” but that might make it sound more fun than it actually is. Replacing it with little more than macho violence, this effort is lacking the Shakespearean underpinnings of the hit FX show, and the solid ensemble of it. This is one of those dramas that can’t balance its incredibly dark tone with something that feels like the journey into the grimy underbelly is worth taking. It’s the kind of film that makes you want to take a shower when it’s over to wash it off. And, yes, sometimes stories of truly violent, evil people are worth examining, but it takes stellar filmmaking or insightful writing, both of which are lacking here. The only thing that really saves it from complete disaster is another interesting performance from Abbey Lee of “The Neon Demon” and “Mad Max: Fury Road.”

“1%” is essentially about a change in power from someone who believes in ruling through force to one who believes in ruling through politics. The latter is a charismatic leader named Mark (Ryan Corr), who has been running the motorcycle club while the sociopath President Knuck (Matt Nable, who also wrote the film) has been doing a stint behind bars. Mark has been working to grow the club and plan for the future, but his younger brother Skink (Josh McConville) gets into some trouble with some rivals. When Knuck gets out, he wants to handle the trouble with violence, whereas Mark knows this will only lead to trouble for everyone. A power struggle ensues, but it’s too difficult to really care who’s going to come out on top. At one point, someone says “He’ll fuck it up for no other reason than he likes to fight.” “1%” is a movie that has almost nothing going on other than a desire to fight.

Brian O’Malley’s “The Lodgers” is a better film, but one I also found frustratingly thin in its efforts to mimic classic Gothic thrillers without enough going on underneath. It starts promisingly, introducing us to a pair of fraternal twins with a very unusual situation. Rachel (Charlotte Vega) and Edward (Bill Milner) are 18-year-olds who were orphaned and left with some strict rules. For one, they’re not allowed to be outside of the house after midnight. For another, they’re not allowed to let anyone into the decrepit mansion in which they live. While a terrified Edward sticks to these rules like a religion, it feels like Rachel is starting to push the boundaries. From the beginning, we know something bad is going to happen if she does.

Shot in an Irish mansion that’s allegedly haunted, O’Malley’s use of the location is one of the film’s greatest strengths, and Vega is a captivating lead. The problem with “The Lodgers” comes down to thinness of concept and character. I just never quite cared about the twins or their predicament in way that would make the final act resonate. There’s enough interesting material to look forward to what O’Malley and Vega do next, but “The Lodgers” is a near-miss for this hardcore horror and Gothic thriller fan. It tries to get underneath, but remains skin-deep.