It’s safe to say that audiences around the country were shocked this weekend by “A Quiet Place”—not just from that nail on the staircase, the uncharacteristic stillness of fellow audience members, or that final shot. Included in the film’s surprising, invigorating experience is witnessing someone previously removed from horror hurl themselves into the genre. Acting as co-writer, director and star, “A Quiet Place” is John Krasinski’s breakthrough as a triple-threat entertainer, but it’s been a long time coming.

Before this past weekend, John Krasinski tried to cement himself as a major director with a very talkative David Foster Wallace adaptation (“Brief Interviews with Hideous Men”) and a Sundance-ready ensemble family dramedy (“The Hollars”). It’s the same ideology that once made Ben Affleck a big surprise—take a workman approach to a recognizable subgenres, and let people be surprised when your directorial credit pops up in the credits—but it hasn’t yielded Krasinski resounding success or critical respect like his third film, the very frightening and very good “A Quiet Place.” By no accident, he’s tackled the horror genre by relying on the unique strength that can be seen throughout his acting work, and one that has made him relatable as an everyman across TV and film—expressive silence.

Years before Krasinski was silently reacting to the supersonic monsters of “A Quiet Place,” there was Michael Scott. The world met Krasinski on “The Office,” as one of many employees at Dunder Mifflin who, when rendered speechless often by Steve Carell’s insensitive, bombastic and in-turn-hilarious boss, shot glances of discomfort at the documentary crew filming them. But Krasinski’s work as paper salesman Jim Halpert elaborated beyond the original comic idea of glancing at the camera in pained recognition, and became an essential part of adding to the show’s deafening, deadpan awkwardness. It also led to numerous stolen romantic moments of pining for his love interest Pam (Jenna Fischer), having to stay silent about his interest in her, but inviting us into his longing.

With the specific expressiveness of his acrobatic brows, wide-eyes and rubbery cheeks, Krasinski was able to define the show’s inclusive comedy through his reactions to uncomfortable moments, his ballooning face and weary glances instilling different themes into the comedic atmosphere: anxiety, discomfort, disbelief, whatever you as a viewer felt when he looks back at you. Krasinski’s comedy let people identify with Jim and his workspace emotionally. It’s telling, then, how this character is one of the show’s most popular, but is far more memorable with his faces than any dialogue or verbal reactions, especially compared to so many other cast members who also break the fourth wall.

Krasinski’s success in “The Office” led to leading roles with many directors who tried to make use of his no-word speciality and his expressive, grounded neuroses, albeit without the crutch of looking at the camera. Ken Kwapis, who directed the first few episodes of “The Office” tried to make him relatable as a young fiancee in the slapstick-y “License to Wed,” as paired with an underused Mandy Moore and Robin Williams as a sociopathic priest. While the film is no gem, it does feature a full-fledged attempt at using his expressive reactions in a way that doesn’t work. Instead of zooms and stolen moments that would catch him as on “The Office,” the movie relies on his pantomiming as the straight-man in the scenario, and it holds him back.

Actor and director George Clooney tried his hand at Krasinski’s charisma with “Leatherheads,” another distinctly old-fashioned comedy, this one set in the 1920s and meant to evoke the films of that era. Though Krasinski has strong moments in slapstick-y scenes opposite Clooney, on and off the football field, the film was another one that helped construct Krasinski’s desired, if synonymous film image: an all-American guy, who often played working class folk (even when he was a Hollywood filmmaker in Ry Russo-Young’s indie drama “Nobody Walks,” he was a sound designer). These roles paralleled his more prominent status as a TV rom-com lead on “The Office,” but didn’t provide a definition as to what made a Krasinski film performance special aside from his reactive energy.

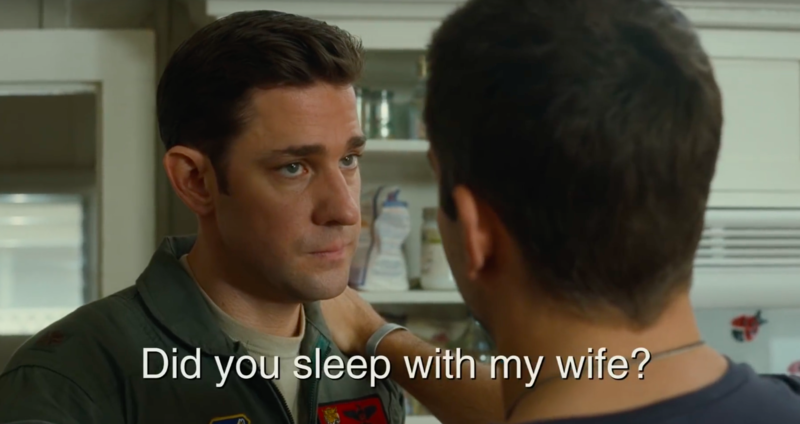

By 2013, “The Office” had ended, and Krasinski only did voice-acting in animated films for a couple of years. But he returned to live-action in 2015 with the summer ensemble comedy and wannabe hit, Cameron Crowe’s “Aloha.” Naturally, Krasinski played a character of very select words, a secretive Air Force pilot named Woody who has a communication problem to the point that it threatens his relationship with his wife (Rachel McAdams), and makes him intimidating to a military contractor played by Bradley Cooper. Krasinski’s performance in this film is one of his most expressive roles, relying on gazes and inner sadness. The metaphorical silence of Woody, and Krasinski’s austere presentation of it, provides a vivid attention about what is not being spoken, and allows the audience to connect with the notion of not communicating in a relationship to the point of being silent (before Crowe later adds subtitles, at least). It grounds the over-baked storytelling, and recalls the movie’s many choruses of which characters look longingly, silently at each other, as if other characters are trying to create Krasinski’s delicate magic. This snippet from the “Aloha” trailer even acknowledges the charismatic, emotional nature of his wordless presence.

Though it was not seen by as many people as I imagine anyone involved with “Aloha” might have expected, the film provided a type of reboot of Krasinski’s film charisma, which would inform a project that lurked in his future, “A Quiet Place.” It introduced the world to a mature, muscular, brooding image of Krasinski, something that would be a prominent part of his lead casting in Michael Bay’s “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi,” which uses his physical nature as much as his worried gazes (his co-star, James Badge Dale, is specifically far more talkative while Krasinski is contemplative). “Aloha” would also be echoed by Krasinski’s second attempt at feature directing, playing a new father in “The Hollars.” By the time Krasinski got to “A Quiet Place,” his filmography was pulsing with paternal machismo, and a desire to prove himself as an entertainer.

This is to say that the emotional success of “A Quiet Place” is no fluke—Charlotte Bruus Christensen’s cinematography is exquisite, and Millicent Simmonds and Emily Blunt are wonderful—but it does come with perfect timing for Krasinski. It fulfills his celebrity magazine sensibilities about the importance of family, and his growing confidence as a director, allowing for visual storytelling that banks on vivid expressions from incredible actors like Blunt and Simmonds most of all. Age is a big benefit too, as his acting style has become more stoic as he gets more wrinkles on his forehead and weariness in his eyes, but it makes his calibrated expressions all the more immediate. Not for nothing, even the usage of sign language becomes a powerful outlet for a face like Krasinski’s, given how it requires usage of eyebrows and eyes for emphasis in communication. It’s a filmmaking environment that he flourishes in, albeit working from a story where you don’t have to know where his character came from, or even his name. He only wants you to recognize that it’s him, acting opposite the superstar Emily Blunt.

“A Quiet Place” is the kind of story you could imagine previous Krasinski characters surviving in, but it’s the Krasinski idea of silence that works within the storytelling itself. With this script co-written by Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, Krasinski has created this obstacle course of silence, with dread that can consume your imagination, as it slams against the anxiety that something might happen to the protagonists in a world where sound equals death. At the same time, the silence is alienating, heightening the emotional moments when characters can steal moments of spoken word (as when he does with his son, or with his wife). Just as Krasinski was able to get audiences to build a connection to audiences relating to his wordless facial expressions in previous comedies, he now uses that silence as an instrument building dread and/or emotion out of a head space you share with his characters.

In front of the camera, Krasinski’s performance is enlivened by his determined nature, and the ability to relate to him through silent, contemplative moments. As he sits on a silo at night towards the beginning of the film, his worn-down face solely lit by a lonely fire, it’s a classic idea of letting the audience share his anxieties and bring their own emotional weight. Or not long after, there’s a special power in watching him slow-dance with Blunt to the tune of Neil Young’s “Harvest Moon,” and Krasinski, weary, focused and ever so still, can only look down to the ground. In the case of Blunt and Simmonds, they have considerably more emotional range than him, but “A Quiet Place” allows Krasinski to be tempered. “A Quiet Place” essentially has him in Clint Eastwood mode, in an environment perfectly catered for his skill set.

While Krasinski’s previously iconic work on “The Office” lives on in streaming perpetuity, along with other building blocks in his filmography, “A Quiet Place” is the closest Krasinski’s film work has come to returning to that iconic nature of inclusive silence, to breaking the fourth wall again. It’s still stunning, after seeing the film twice now, that Krasinski nailed the thrills of the genre as well as he did with “A Quiet Place,” which opens up his potential as a filmmaker. But even if he goes on to even more ambitious or prestigious movies, “A Quiet Place” may very well be the definitive project of his career.