Janet Leigh Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention Janet Leigh

Janet Leigh dies at age 77

Roger Ebert

Psycho: Murder in close-up (without bodies)

Jim Emerson

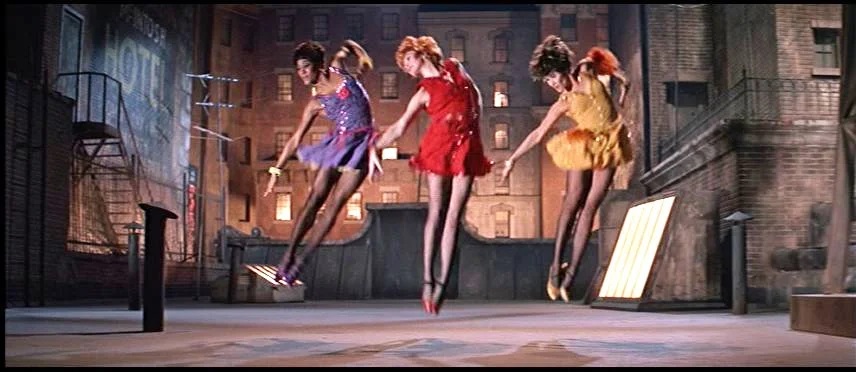

Broadway Legend: Chita Rivera (1933-2024)

Nell Minow

Angela Bassett, Jamie Lee Curtis, Brendan Fraser, Cate Blanchett, Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson Feted at SBIFF 2023

Donald Liebenson

30 Minutes on The Manchurian Candidate

Matt Zoller Seitz

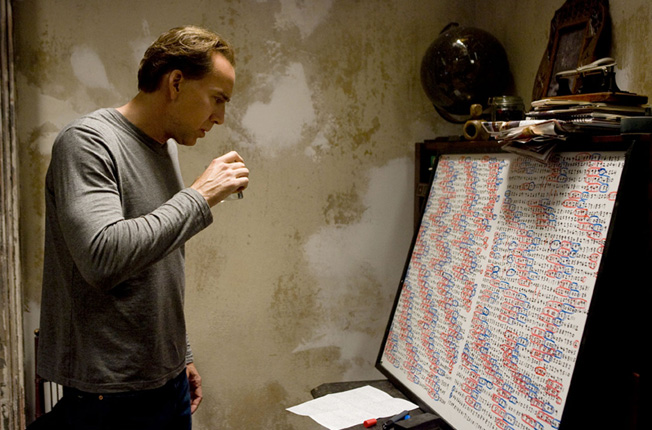

30 Minutes On: “Beautiful Boy”

Matt Zoller Seitz

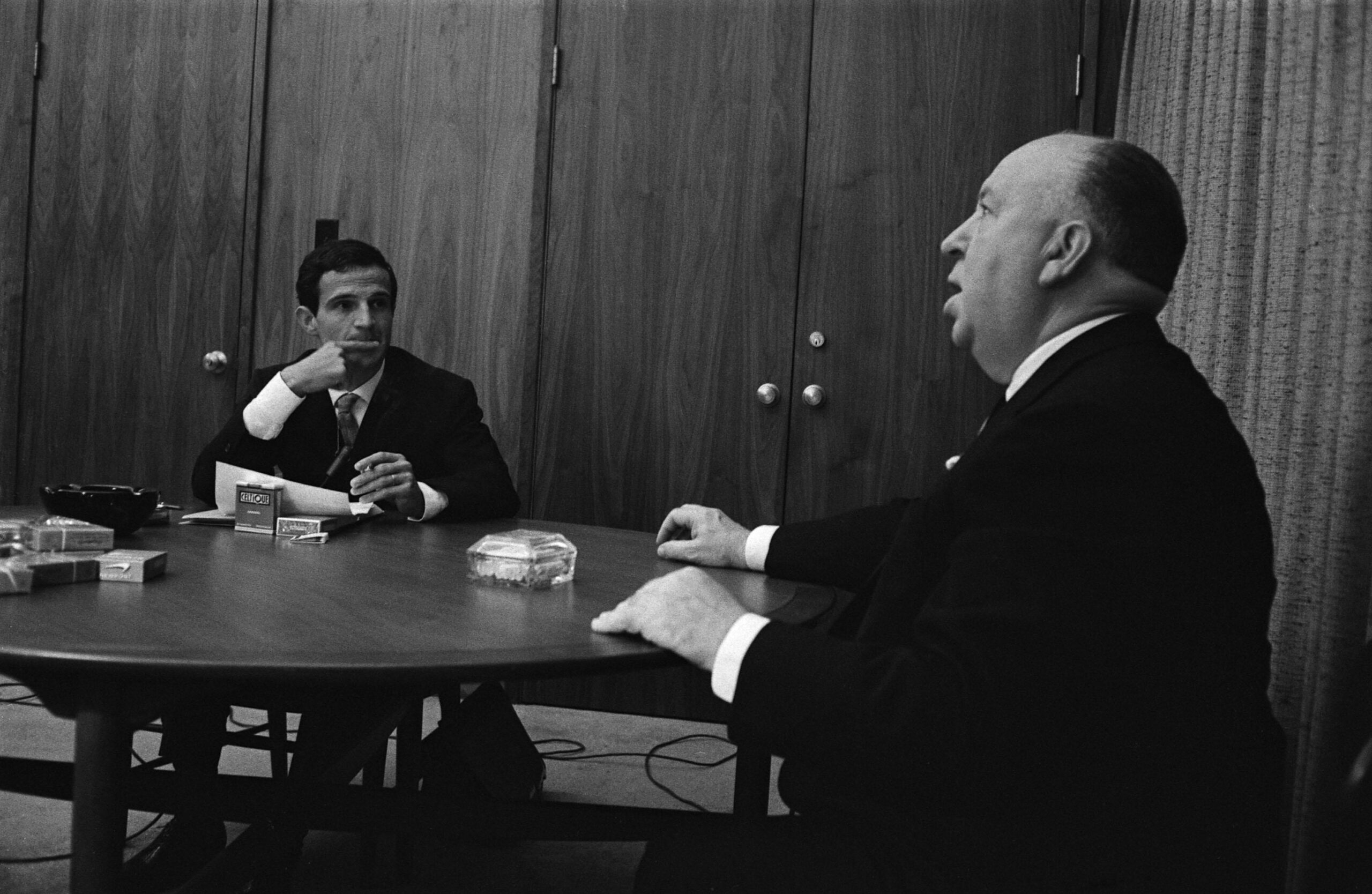

Hot Docs Interview 2017: Alexandre O. Philippe on “78/52”

Matt Fagerholm

Hot Docs 2017: “Maison du Bonheur,” “Becoming Bond,” “78/52,” “Erotica: A Journey Into Female Sexuality”

Matt Fagerholm

John Hurt: 1940-2017

Brian Tallerico

Sundance 2017: “78/52”

Walker King

Chinese New Year: Monkeys, Poems and Spoiler Alerts

Jana Monji

30 Minutes on: “Halloween”

Matt Zoller Seitz

Cannes 2015: “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” “Green Room,” “Love”

Ben Kenigsberg

Thumbnails 10/9/14

Matt Fagerholm

Lenses and Reflections: “I Origins” and the history of the eye closeup

Alan Zilberman

Zombies in the Outfield and Cats in the Owner’s Box; the Top Ten Odd and Overlooked Baseball Movies

Bob Calhoun

Brian De Palma’s Films, Ranked

Peter Sobczynski

The most emblematic rooms in movies

Roger Ebert

Stars under the stars, for free

Roger Ebert

TCM’s 15 most influential films of all time, and 10 from me

Roger Ebert

Ebert: The Night Watcher

Roger Ebert

Hitchcock is still on top of film world

Roger Ebert

Opening Shots Quiz 2: Answers

Jim Emerson

Movies 101: Opening Shots Project

Jim Emerson

A boy’s best friend is his mother

Wael Khairy

“Blade Runner:” Great, but a little dull

Gerardo Valero

The Girl: Putty in Hitch’s hands

Jeff Shannon

Welles film is restored to intended glory

Roger Ebert

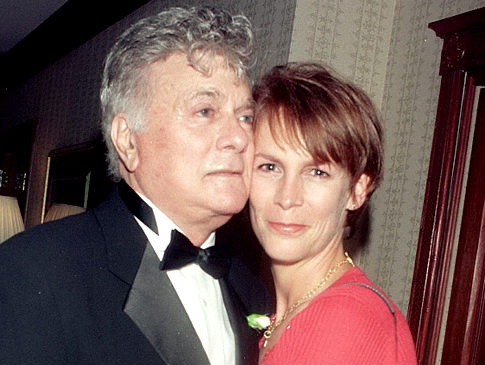

In memory: Tony Curtis, 1925 – 2010

Roger Ebert

Jamie Lee Curtis: “Blue Steel”

Roger Ebert

Hitchcock: He Always Did Give Us Knightmares

Roger Ebert

The Master of Suspense is Dead

Roger Ebert

I know I’m right about ‘Knowing’ and its critics were unknowing

Roger Ebert

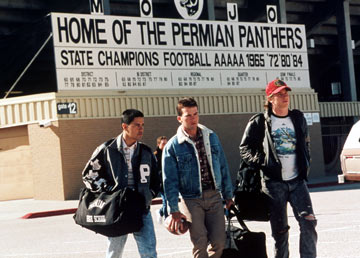

We’re not in Texas anymore… are we?

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (07/26/1998)

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (12/15/1996)

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox