In his review of “Side Effects,” Roger Ebert discussed the threads of Steven Soderbergh’s works: “Crime. Sex. Complicated yuppies. Smart people doing heedless things. Corruption in high places.” Such threads are the key ingredients to genre films. Yes, Soderbergh has made big budget Hollywood movies—the “Ocean’s” trilogy, “Magic Mike,” and his one-two Oscar-winning punch of “Erin Brockovich” and “Traffic” from 2000. These types of movies get him back in the good graces of audiences, studios and critics. Soderbergh’s preferred sandbox, however, is the experimental, instinctively stylistic and smaller B-movie.

“The Limey” is the latter type of Soderbergh movie. What he described as “a minor work” solidifying his “standing as a cult failure” is a mission statement. Released 20 years ago this month, “The Limey” shows a filmmaker preoccupied with new plot devices, but the style adds substance. The movie signaled Soderbergh’s commitment to a “John Huston plan for career longevity,” as he described to Salon in 2000.

“I’ve been trying to carve out half-in, half-out of the mainstream ideas for genre films made with some amount of care and intelligence and humor,” Soderbergh told Salon, explaining that his goal was “to see if we can get back to that period we all liked in American cinema 25 years ago.”

By 1998, Soderbergh had won over audiences and critics with the Elmore Leonard adaptation “Out of Sight.” Finally, after nine years of labored-over duds like “Kafka,” “King of the Hill,” “The Underneath,” and the free-wheeling, no budget lark “Schizopolis,” the director had a successful follow-up to his Palme d’Or-winning debut “Sex, Lies, and Videotape.” What changed? Soderbergh’s approach.

“I wasn’t interested in making films about me anymore,” Soderbergh told Salon. “As somebody once put to me, bluntly, ‘If you think Hollywood movies are so fucking terrible, why don’t you try to make a good one instead of bitching about it?’”

Free of the pressure of following up the festival favorite of independent cinema, Soderbergh leaned into his instinct while playing the business side of making movies, creating a niche where, for every crowd pleaser, he’d make a smaller, seemingly more personal indie.

“The Limey” is the point when Soderbergh confidently admitted his comfort zone is the genre film. Within that structure, he could push new ways of storytelling. The learning curve part of his career now in his rearview, he knew how to make smaller movies more efficiently and on the cheap.

Filmed between June 1998 and March 1999, “The Limey” started as a script that Lem Dobbs wrote when he was 19 years old, imagined as a “Get Carter”-type revenge story. By the time Dobbs and Soderbergh got to make “The Limey,” they agreed to make it a deconstructed B-movie. The degree of the deconstruction was up for grabs, and Dobbs thought it could be pushed even further after the film was released.

What makes “The Limey” great today is that it clearly shows what makes Soderbergh tick—the devices used to present characters, action and story. “I’m interested in layers,” Soderbergh says in the film’s now-legendary commentary track. “(I’m interested in) revealing characters in ways that are unorthodox. I’m preoccupied with new ways of telling a story. I like puzzles. I like mosaics.”

At its core, “The Limey” is a revenge movie. Terence Stamp plays Wilson, an aged British thief who lands in Los Angeles looking for answers surrounding the death of his daughter, Jenny. However, “The Limey” isn’t a cold, straightforward exercise in the genre, or the precursor to “Taken.” Dobbs imagined “The Limey” as a movie that explored themes like family, the battle between capitalists and communists, and how the dreams of the ‘60s fell apart. Through casting, editing and filmmaking devices, Soderbergh then pulled the movie back to the central relationship of Wilson and Jenny, with bits of Dobbs’ other themes in the revenge movie framework.

“The movie is very much a character piece, and I wanted more of a sense of the relationships, sense of families, but you backed off,” Dobbs says on the commentary track.

“You get in the editing room, playing to the strengths of the piece, and I was most interested in Wilson and the daughter,” Soderbergh responds. “I knew the more time spent away from that would dilute the intensity of that relationship.”

Instead of going the conventional route, Soderbergh edited the film into “a memory piece,” full of repetition, overlapping dialogue, and disjointed sequences. The result is an experimental movie with an unpolished, stripped down feel that is as interested in exploring the possibility of storytelling devices as it is the father-daughter relationship. Each choice—no matter its size—is key and more fascinating with each viewing.

Against a pitch black screen, “The Limey” starts with Stamp’s Wilson angrily demanding, “Tell me, tell me about Jenny,” a command we’ll hear again. As the opening credits roll, Wilson lands in Los Angeles while The Who’s “The Seeker” plays in the background. Outside the airport, Wilson is out of his element, a man from a different time and place, pulling at his tie, grimacing at the sight of cops and pacing a hotel room before resolving to do what he came to Los Angeles to do—find out about Jenny (Melissa George). How we learn about Jenny’s death is through a quick shot of a newspaper article headlined, “Woman dies on Mulholland.” Wilson had been carrying the clip in its original envelope, sent by Jenny’s friend Eduardo (Luis Guzman).

The film sets in motion as Wilson meets with Eduardo, finding out more details about his daughter. The conversation moves organically as the locations jump from Eduardo’s back porch and car. More repetitive imagery comes with shots of Jenny driving and the bright orange burn of the car fire Jenny died in. As Eduardo tries to explain the situation to Wilson, the locations jump more frequently, making way for more sequences full of repetitive imagery: shots of Wilson making his way down a brightly-lit warehouse wall in downtown Los Angeles, Jenny riding with Eduardo, and Jenny confronting a group of men. Eduardo’s details about Jenny’s life is laid over the sequence. Eduardo is stressed at first glance of Wilson, but finds a connection—the men are both ex-cons. We see a small shot of Eduardo’s barbed wires, then Wilson mentions how he just got out of prison. The new friendship is made as Wilson tosses over his pack of cigarettes to Eduardo.

The sequence is Soderbergh’s way of “being more adventurous in giving that information,” he said in the commentary. It wasn’t a new style for Soderbergh—he had been messing with chronology in storytelling from the time he first picked up a camera, and in unsuccessful movies like the 1995 crime drama “The Underneath.” But in other, previous films, Soderbergh wasn’t working as quickly or effectively. He would usually labor over each decision, feeling pressure to follow-up “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” with another masterpiece, or in “The Underneath”’s case to properly remake “Criss Cross,” a 1949 film noir starring Burt Lancaster.

For “The Limey,” Soderbergh leaned into a quicker work ethic (especially after receiving guidance from “A Hard Day's Night” filmmaker Richard Lester) with an energy that’s on full display. Memories of Jenny are full of lens flares; shots throughout the movie use only available light, giving scenes a fluorescent light-type feel. Soderbergh also refers to the movie as a point where he began to use more handheld cameras, setting up shots with multiple cameras, giving actors space and freedom for spontaneity.

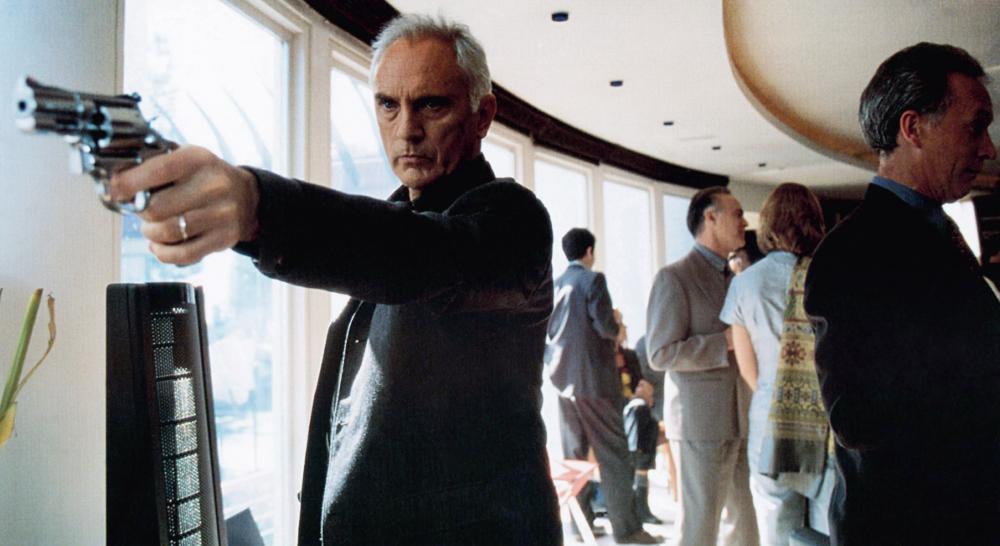

With these devices and Soderbergh’s appreciation for 1960s aesthetic, “The Limey” quickly establishes that its story won’t be a straightforward tale, and that its violence will be oblique as well. The key warehouse scene, where Wilson confronts Valentine’s goons, is shot how it was written by Dobbs—the action taking place from a distance. A couple of goons throw Wilson across the street from the warehouse, then the camera stays where Wilson was dropped as Wilson heads back in, picking off the goons. As Wilson exits, his face is drizzled with blood, and the camera zooms across the street to his angered face, yelling, “You tell him! Tell him I’m fucking coming!” Even more action throughout the film is shot through windows, including Wilson’s initial confrontation with the warehouse foreman (William Lucking), when Wilson later throws Valentine’s guard off the side of Valentine’s house, and a shootout during the finale.

Soderbergh adds another layer of emotion to “The Limey” with the use of footage from Ken Loach’s 1967 “Poor Cow,” to show Wilson’s past. “Poor Cow” was one of the few films “where Stamp looks like himself,” Dobbs said. Loach’s film also has a “grainy, documentary look” giving the used footage a “feeling like memories.” Like the repetitive imagery, the “Poor Cow” scenes are the literary device of “show, don’t tell.” What could be an overwrought monologue about Wilson’s past becomes a simple, effective and usually silent scene cut into a sequence, showing Wilson’s relationship with his wife, his daughter and his friends, as well as the consequences of Wilson’s crimes.

By casting stars like Stamp, Fonda, Warren and Barry Newman (who plays Valentine’s security consultant Avery), Dobbs and Soderbergh already achieved a certain establishment of that “death of the ’60s” storyline they wanted. Soderbergh praised that he couldn’t “quantify the emotional quality” of Stamp’s performance, “that when you see his face, his emotion, you’re seeing his implosion.” As scenes move, Stamp gives Wilson natural reactions to his surroundings, like when he buys a gun at a playground or thinks of his daughter from the plane.

Fonda, an icon of movies like “Easy Rider” and “Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry,” plays Valentine like a Robert Evans-type producer. Valentine is “certainly not a person,” he’s “more like a vibe,” as his new flame describes him. Fonda’s character is even introduced with a mid-movie trailer. As The Hollies’ “King Midas in Reverse” plays in the background, Valentine talks business on a cell-phone by the pool of his Mulholland Drive loft. His house is full of gold records. He smiles, laughs, sips something strong, then appears on an American Express billboard.

Newman, an actor known for roles in cult classic movies like “Vanishing Point” and “Fear is the Key,” plays Avery, a man who keeps Valentine out of harm’s way. He “has appearances to keep up,” Avery tells a crude hitman named Stacy (a ponytail-wearing Nicky Katt). “Who cares about you?,” Avery continues. “Not even God.” The small exchange establishes the class antagonism Dobbs wanted to explore while introducing the low-class sleaze of the hired gun. It also further shows Avery’s get-it-done attitude. A security consultant, Avery is a “no fuss, no muss” type of guy who wears a suit while taking care of dirty work with a shotgun in the passenger seat.

In Warren’s Elaine, the movie finds its conscience. An actress and voice coach who was Jenny’s older best friend, Elaine lives in an apartment filled with outdated furniture, a nice-enough view and an old picture of one of her movies on the wall. After Wilson and Elaine discuss Jenny and Wilson’s absence in his daughter’s life, Elaine balks at Wilson’s plan “to talk” to Valentine. “You guys and your dicks, man,” she says. Wilson is careful not to make Elaine too mad, though, as she is the closest Wilson can get to remembering Jenny.

With Elaine, Wilson finally opens up in a continuous monologue, remembering his daughter as he talks to Elaine at the dock, in her apartment, and over dinner. Later on, when captured by DEA agents who are also on Valentine’s tail, Wilson gets caught up in a story, remembering Jenny. The sequence is cut with footage from “Poor Cow,” brief shots of a younger Jenny threatening to call the cops, and Jenny at the beach. Soderbergh is fascinated with the repetition because each shot in these memory sequences has a different meaning, adding different emotional weight at different points in the story.

The finale between Wilson and Valentine is also atypical from the revenge thriller. “We knew we had a good left-handed turn coming,” Soderbergh says. “That was our goal, the injection of the daughter and how the past affects the present added an undercurrent we’d like to see in these types of movies.” As Wilson does confront Valentine on the beach, the imagery of Valentine’s hands grasping at Wilson repeats alongside the revelation and truth of Jenny’s death. Dobbs wanted to go on that route, too. “The memory is a form of regret,” Dobbs says. Wilson is a character “questioning his entire life, the path not taken,” thinking about how his life could have been different.

“The Limey,” like many of Soderbergh’s smaller, more experimental films was a box office flop, but it was made on the cheap at $9 million. It also had the good fortune of coming in between Soderbergh’s newest hit, “Out of Sight,” and his string of award winners in 2000, “Erin Brockovich” and “Traffic,” both of which were box office hits. Now, such a market for a film like “The Limey” doesn’t exist.

Just as “The Limey” is full of characters out of their element trying to maintain the energy of their youth, the movie reminds us of a now-lost era at the box office when movies like this, that Dobbs and Soderbergh loved, existed and played to mainstream audiences. And just as Wilson is a character out of sorts with his environment, Soderbergh is a big-name, award-winning filmmaker consistently at odds with whatever Hollywood is pushing onto audiences (even in his “crowd pleasers”). How he’ll tell the next story, no one knows. You’d be a fool to even try and predict it, too. But that’s what keeps us, and Soderbergh, coming back.