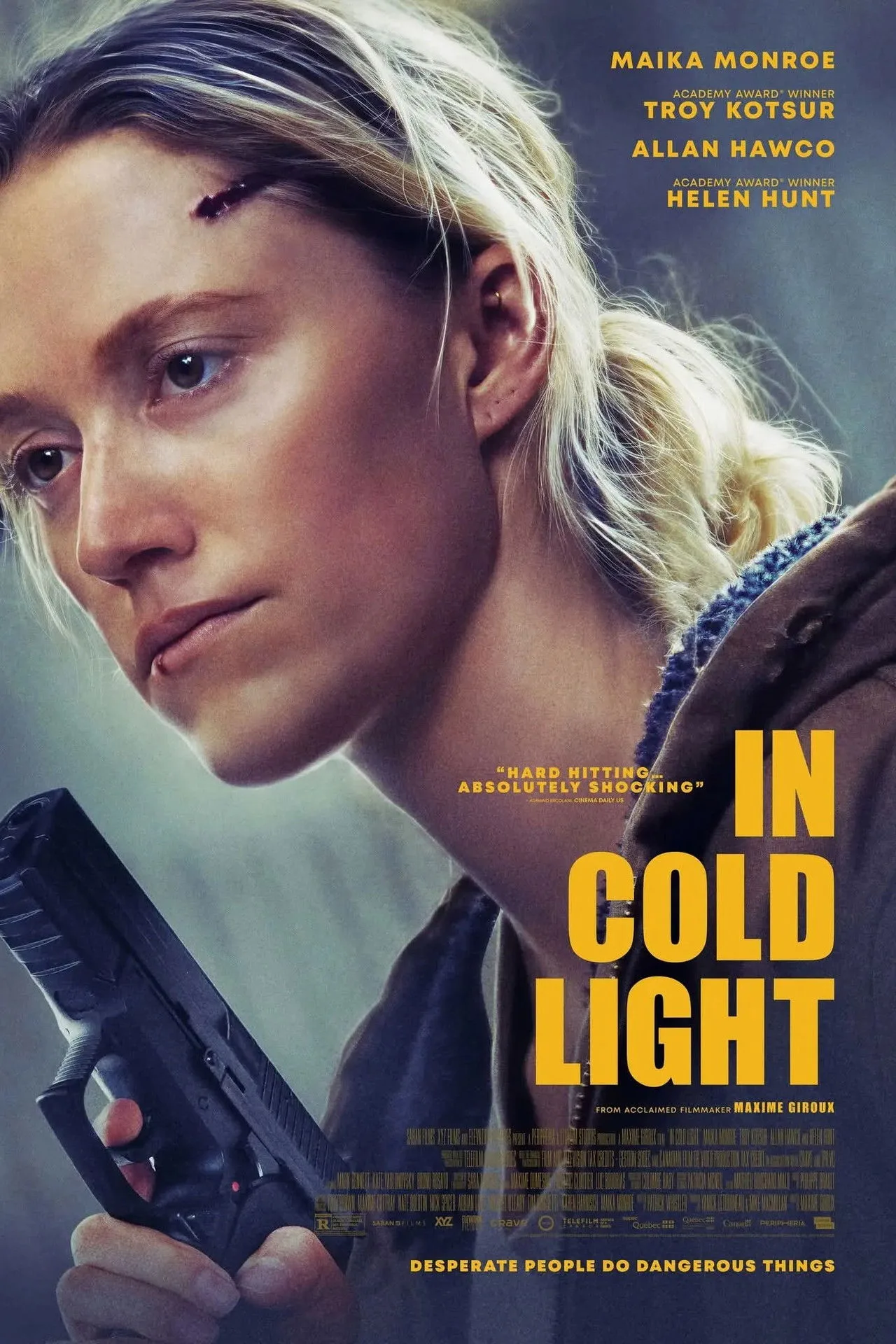

You don’t expect melancholy blue-mood ambiance in a fast-paced thriller, and this gives “In Cold Light” an emotional foundation it might not otherwise have. The film starts with a woman being chased by the cops; she barely stops running for the entire film, yet there’s this deep, quiet intensity underneath it all. Directed by Maxime Giroux, the film rarely lets up, but it is interested in character and environment, in mood and emotion, not just plot.

When we first see Ava (Maika Monroe), she is jumping through a second-floor window of a drug house to escape the police officers who just busted through the door. She doesn’t seem like a scared newbie. She and her twin brother Tom (Jessie Irving) are dealers, and their drug operation is small and scrappy, but it’s all they seem to have. Ava and Tom are “lost” children. Their mother died when they were young. They take care of each other. Their father Will (Troy Kotsur, who won an Oscar for his performance in “CODA”) is a battered old bull rider, mean-spirited and intimidating. He keeps his distance from his kids, particularly Ava. Tom has a girlfriend and a new baby (which will come into play later).

Ava is adrift by comparison. She does some jail time for the drug bust and gets a job at the rodeo upon release. When her parole officer asks what she wants out of life, Ava says, “To be free. To be alone.” You believe her. She’s so locked deep within herself. Following a sudden and shocking act of violence, Ava has to go on the run again. She is always just about a foot or two ahead of her pursuers.

Patrick Whistler’s script falls into some cliches but avoids others. What is unspoken is more important than what is said, and the characters who are articulate tend to be up to no good. (Helen Hunt plays such a character in what could have been a glorified cameo, but, in her hands, is something far more substantial.) Eventually, Ava and her dad have the confrontation that’s been brewing all along, and it takes place entirely outside his house, in sign language (Kotsur, of course, is Deaf). A nice detail is the motion-detecting light turning off at times when there’s no movement between them, and so either Ava or her dad randomly waves their arm in the air, mid-argument, to turn the light back on. The film is full of specifics like this.

Giroux is interested in the rhythm of the whole rodeo world, and he and cinematographer Sara Mishara dig into how it looks and feels, the tunnels leading to offices and locker rooms, the sounds, the people, the tall rodeo lights blurring and dazzling through the blue-black night sky. The location isn’t just background noise. There’s a poetry and a grit to the environment.

Much of the film’s power and gravitas comes from Monroe’s presence. The stakes of the film are life or death, typical for a thriller, and Monroe’s face, deep with feeling beneath a stoic mask, carries those stakes, propelling the film forward. Monroe has been working in almost stealth fashion for over a decade now. She’s occasionally been cast as “the girlfriend” or “the pretty girl,” but she’s had opportunities to show what she can do in genre films, like the effective “It Follows,” or the recent “Longlegs,” as well as the fantastic (and criminally underseen) “Watcher.” She’s set free in a genre context and is powerful enough to hold the center of a film. What makes Ava tick in “In Cold Light” is somewhat explained in a couple of flashbacks that show childhood events, but these are unnecessary. Monroe’s face tells us everything we need to know.

A lot of thrillers are exciting but empty. “In Cold Light” is thrilling but very full in unexpected and complicated ways.