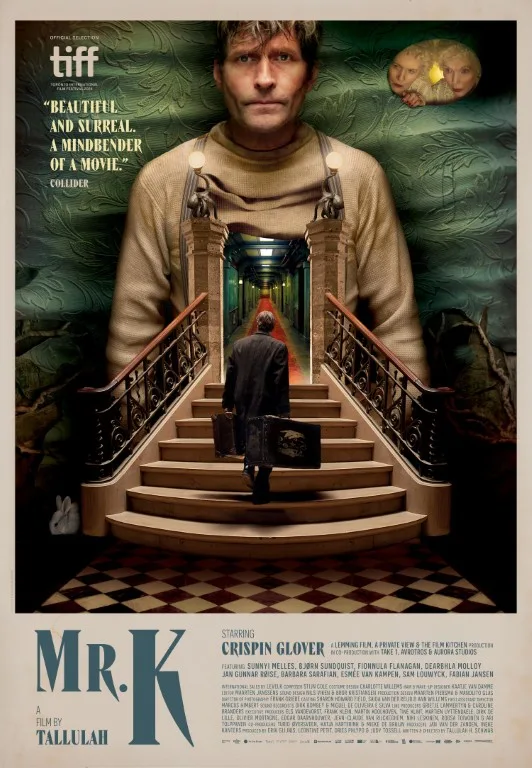

Casting eccentric actor/performance artist Crispin Glover as your lead sends a message to viewers, whether you’re open to it or not. Glover plays the title character in “Mr. K,” a sort of Kafkaesque fantasy about a traveling magician who can’t find the exit from a hotel whose walls are mysteriously contracting. Nobody else in the hotel seems to notice or care about this strange predicament, and many of them carry on like it’s business as usual. Mr. K, on the other hand, resists his stifling new reality. Or he tries to, at least.

Glover’s baggy role doesn’t really suit his weird charms. He’s believable on a scene-to-scene basis, but it’s sometimes unclear what motivates Mr. K or why others are drawn to him. So while casting Glover as a reluctant everyman takes admirable chutzpah, there’s not much to “Mr. K” beyond its second-hand surrealism and strained counter-mythmaking.

Mr. K begins his story with a spacey/vague maxim, related through a halting voiceover narration: “Every being is a universe within themselves, floating about in eternal darkness.” That line negligibly sets up the movie’s dream logic conclusion, which seems to hail from a different movie altogether. Most of Mr. K’s story feels like leftovers from the whimsical and ostentatiously designed movies of formerly revered French pop artist Jean-Pierre Jeunet, though flashes of other filmmakers and styles appear throughout. “I’m no one,” Mr. K sighs repeatedly, hoping to establish how unremarkable and therefore unworthy he is of such a strange fate. Unfortunately, he fits right in since the rest of the hotel and its inhabitants are also too vague to stand out.

Once Glover’s character checks in, he tumbles from one encounter to the next without much agency or sense of when or why he must keep moving. Now he’s talking to a pair of reclusive and seemingly well-to-do twin sisters, Sarah and Ruth (Dearbhla Molloy and Fionnula Flanagan). Now he’s being chased down the hall by a marching band that emerges from inside the hotel’s walls. Now he’s a member of the building’s kitchen staff, initiated by fellow nobody Anton (Jan Gunnar Røise). Now he’s struggling to lead a rebellion against the hotel’s vague social hierarchy—pampered guests, uneasy kitchen staff, and hungry refugees—based on a prophetic rumor about a “liberator” who will save the hotel from itself.

This leads one to wonder: Crispin Glover’s supposed to be a leader of men, if only by accident? The guy who almost karate-kicked David Letterman and who also recently performed a live spoken-word slide show at the Museum of Modern Art? The rat-stoking creep from the “Willard” remake and Marty McFly’s stammering dad? The malcontent office worker from “Bartleby” and the singer of the “Clowny Clown Clown” song? That’s the guy?

Banishing these stray associations shouldn’t be so hard, especially if you’re focused enough on Glover’s sweaty and often captivating body language. Mr. K’s supposed to be a magician, after all, even if his suitcases are taken from him early on in the movie. That kind of contrivance is par for the course, given the overwhelming churn of events that shunt Glover’s protagonist from one encounter to the next.

That said, how does Mr. K relate to Anton and his fellow kitchen staff, or adapt to taking orders from the hotel’s imperious head chef (Bjørn Sundquist)? And why does it seem more important to establish that Mr. K’s not a natural leader than whatever he might actually be? There’s a man-sized hole where this character’s personality should be, and while that’s partly intentional, I never got the sense that Glover’s performance was the main draw that it should be.

Casting Glover as the lead in your dreamy fable is a bit like using durian juice as the base for your buttermilk cupcake’s icing. You can do it, but you also need to ensure that your unusual centerpiece blends well with the rest of your ingredients. The makers never pull that feat off. It doesn’t help that the movie’s polished, but unoriginal, production design mostly draws attention to itself. The dialogue also never explains anything that Glover’s performance doesn’t already suggest. The biggest problem with “Mr. K” still concerns Glover, who’s most convincing in character when he’s rejecting whatever’s set in front of him.

Most of what works in “Mr. K” stems from its poised visual presentation, particularly the way cinematographer Frank Gribe collaborates with writer/director Tallulah H. Schwab to make every group shot appear like a landscape portrait. Most of the camera’s frame is used to foster a sense of perspective, rather than centering on whatever’s in the middle or to the side of the image. That’s not nothing in such a visually-oriented movie. It’s also not enough in a mysterious allegory where the main constant is that no matter where Glover drifts on screen, he’s always bound to seem lost.