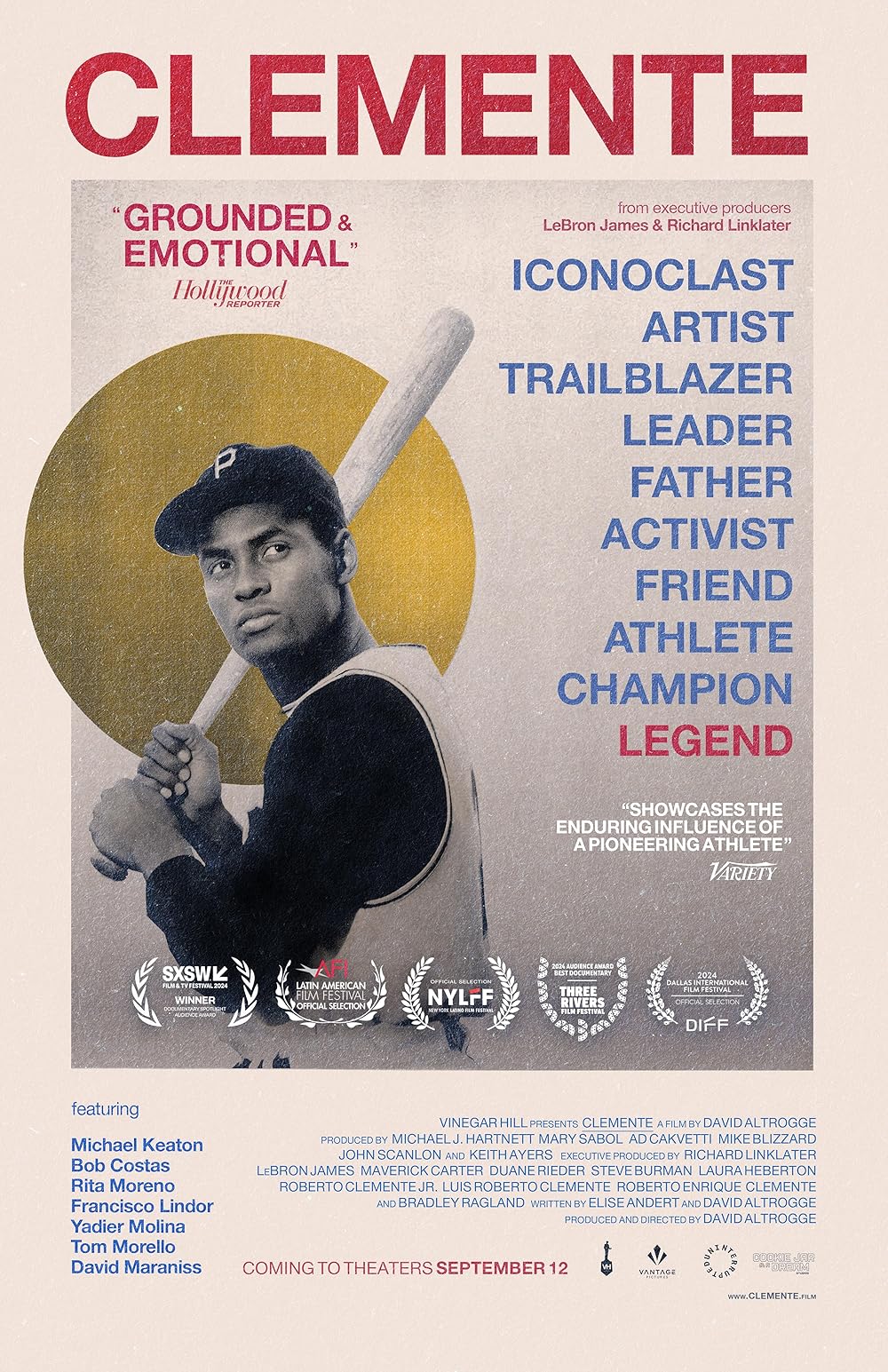

In the history of baseball, 33 players have 3000 or more career hits. But only one man has exactly that number: the late Puerto Rican player Roberto Clemente. A 15-time all-star, 12-time Gold Glove winner, and 2-time World Series winner, the Pittsburgh Pirates legend died prematurely in a plane crash on December 31, 1972, while transporting emergency relief goods to a Nicaraguan populace still reeling from a devastating earthquake. Since his passing, he has been remembered not just as a phenomenal ballplayer but also as a model humanitarian. David M. Altrogge’s crowd-pleasing hagiographic documentary “Clemente,” which premiered at SXSW 2024, attempts to remember the baseball Hall of Famer through the words of those who knew him best.

With the arrival of the 101-minute documentary comes the opportunity to remember Clemente as he hasn’t been remembered before. While Jackie Robinson’s #42 is retired throughout all of baseball, Clemente’s #21 remains active for most teams (although there is an annual Roberto Clemente Award given to the year’s most humanitarian player). This past season, Clemente’s former club, the Pirates, landed in hot water when the owner decided to take down his number from PNC Park’s right field corner to make room for an ad. Outside of ESPN’s “The Clemente Effect” and an “American Experience” film, there aren’t even that many documentaries about him. Which is why Altrogge’s admirable but mythological take on him is so disappointing.

“Clemente,” for its part, is well aware that he’s not gotten his just due. The film opens on archival footage from September 30, 1972, when the ballplayer got his 3,000th and final hit. Following that celebratory moment, Altrogge moves to Clemente’s final televised interview, conducted on WIIC, wherein the interviewer notes that Joe Namath received the cover of Sports Illustrated in the same issue that dedicated only a couple of sentences to Clemente’s historic achievement. Judging by this documentary’s easygoing approach, Altrogge wants to use his film as a full-spread story on Clemente. The decision pushes Clemente the man into being a mere memory.

Conversely, Altrogge tries several methods to revive Clemente’s life. Animated sequences give us his origin story: His sister, who wished for a brother, tragically died from heavy burns following a freak accident (an incident that always made the ballplayer aware of his mortality). Altrogge also returns to that archival interview so we can hear Clemente in his own words when he explains the resourcefulness he and his friends used as kids to create their own baseballs and gloves. Clemente would later receive a glove as a gift from Monte Irvin and become a multi-sport athlete in all the activities: track and javelin, which would make him perfect for baseball.

At every turn, Altrogge leans on mythmaking as his mode of reporting. That isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker. Baseball is an apocryphal sport filled with many tall tales and opportunities for deification. Was Cool Papa Bell so fast that if you turned off the light, he could be in bed before the room was dark? Who cares? It’s a great story. And while the director might make the argument that Clemente’s biographical details are facts, because they are, when only the broad beats are shared, the story might as well be a fairytale.

The talking heads further establish the legend. Former baseball players like Yadier Molina—who says he first saw Clemente as a photo next to Jesus Christ—and Curtis Grandson marvel at him like he’s a God. Those who played with Clemente have nothing but good things to say about him. He was apparently a man without vices or faults. Interviews with famous admirers, such as Tom Morello and Michael Keaton, tell us even less. When his surviving sons remember him, they think of him only as a loving husband to Vera Clemente—she also appears in interviews conducted before her 2019 passing—and as a devoted father. When one son claims he has some dirt to share about his dad, it’s about his father purposefully hitting a bone-shattering liner back at Bob Gibson after Gibson told him to go back to where he came from. That’s impressive, but it’s not really dirt.

All of this isn’t to say the documentary needs to provide salacious details about a national hero who uplifted every Latin American player who came after him, but there should be some defining characteristics that couldn’t be gleaned solely from reading newspaper clippings. Instead, real nuggets, such as Clemente being a hypochondriac, wanting goat’s milk rubbed on his body, or the origins of his using the basket catch, are few and far between. There needs to be more details about who he was as an everyday person, instead of opting to look for as many saintly stories, like proving he was a man of the people by finding fans he made lifelong connections with, as can fit in a documentary.

The depiction of Clemente’s baseball career has far more life and verve. The film talks about the discrimination he faced as a dark-skinned Latin man who spoke with an accent. Newspaper articles where they quote him as getting a “heet” are telling, and radio announcers assimilating him by calling him “Bobby” are ghastly. The rapid-fire editing provides us with his major highlights—his performance in both World Series (1960 and 1971) —and shows off his powerful arm, prodigious speed, and sweet front foot swing. These moments, plus the hurt in the voices of those who love him and still can’t believe he died in that plane crash, tell a richer and fuller story about his effect and determination than any glamorous tale could ever hope to communicate about the person Pirates fans called “the great one.”