Michael Angelo Covino’s “Splitsville” sets its tone from its first scene, as a sexually charged encounter between Carey (Kyle Marvin) and his wife Ashley (Adria Arjona) goes sideways, resulting in both a possible death and a visual dick joke. Life, death, and sex. What else really matters?

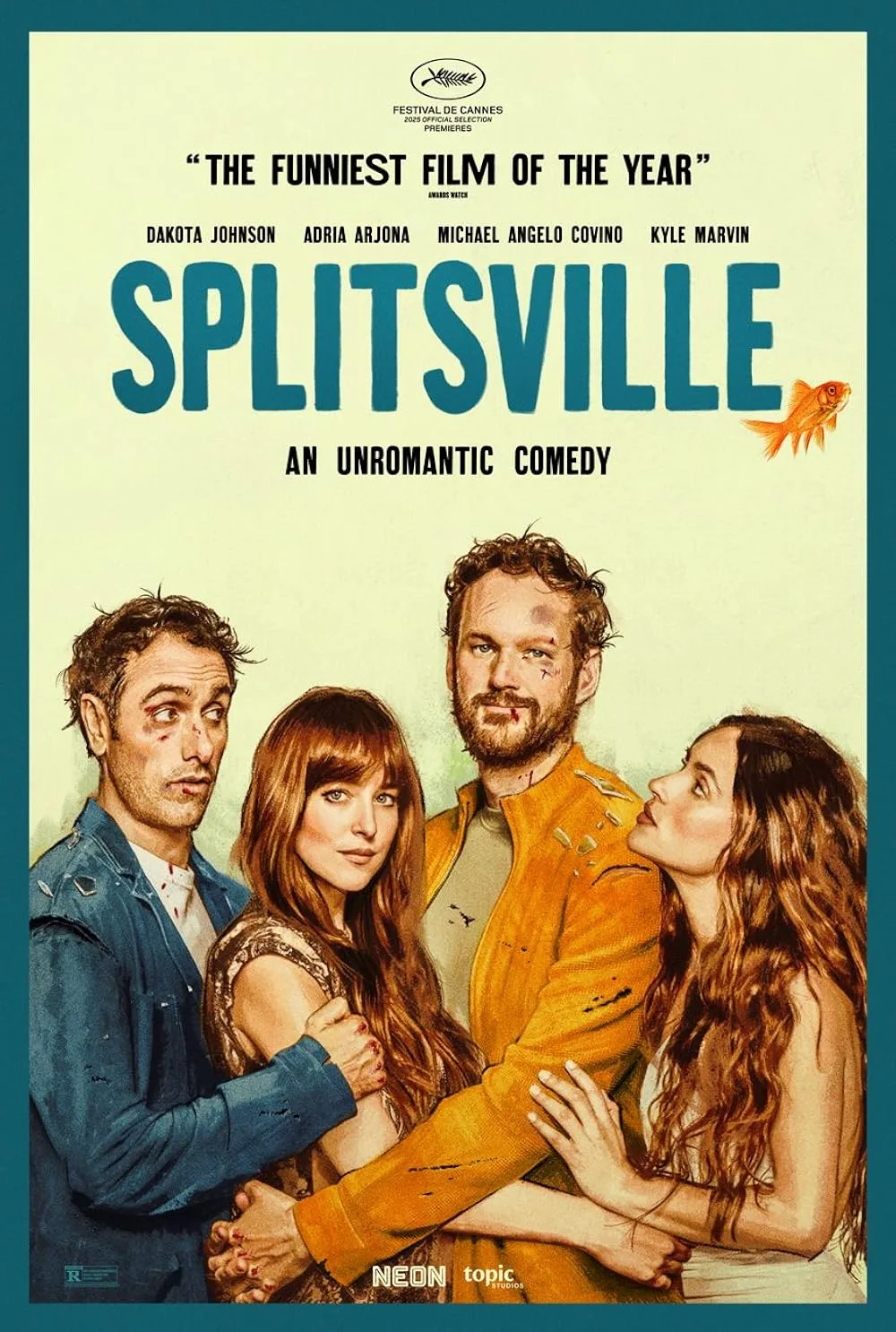

Billed as “an unromantic comedy,” Covino’s is a film that recalls comedies of the ‘70s in its willingness to allow its quartet of lead characters to be horny, problematic, and generally idiotic. Most importantly, it’s consistently funny as Marvin and Covino (who share screenplay credit) bounce their deeply flawed characters off each other in a manner that exposes their relatable weaknesses but never turns them into the kind of comedic idiots that act irresponsibly just for laughs. It’s also gorgeous in a manner that feels likely to be underrated, shot by Adam Newport-Berra, who lensed the stunning “Last Black Man in San Francisco,” a pleasant reminder that movie comedies don’t have to look like TV sitcoms.

After that table-setting dick joke, Ashley tells her husband that she’s been sleeping around and wants a divorce. Carey hysterically leaves the car, running through fields and backyards as the credits roll, eventually arriving at the gorgeous beach house of his friend Paul (Covino) and his wife Julie (Dakota Johnson). He tells them the bad news and is shocked to discover that Paul & Julie have an open marriage. She’s convinced Paul is sleeping with people anyway when he works late in the city; he would rather let her be happy than lose her.

You can see where this is going, but one of the joys of “Splitsville” is that the bed-hopping doesn’t emerge from an antiquated macho vision of manhood. Yes, it takes a certain amount of hubris to write a movie in which Adria Arjona and Dakota Johnson are fighting over you. Still, Covino and Marvin often allow their characters to be the butt of the joke, rather than suave leading men. Marvin is instantly likable, while Covino’s Paul is a bit abrasive to start. But he softens as his world falls apart, discovering that he doesn’t want an open marriage if it’s his BFF who enters.

Covino, who also made 2019’s “The Climb” with Marvin, tells his story episodically, often jumping over large chunks of time between key moments in the trajectories of his four leads. Ashley plays around with her sexual freedom; Carey bounces in and out of Julie’s life; Paul struggles with a work crisis; Nicholas Braun shows up for a hysterical bit as a child’s party magician. It works almost like a series of short films, building on Paul and Carey’s insecurities as comedic foundations, exposing their idiocy in a manner that will come off as unlikable to some but never feels desperate to me. So many comedies are eager to please, desperate to barely satisfy a cross-demo audience—none of “Splitsville” feels overly focus-grouped or sanded down for mass consumption.

If they had test-screened it, they might have gotten a note about the ladies. Where Covino and Marvin falter is in the female characters, who are both drastically underwritten, especially in comparison. Luckily, both performers do a lot of heavy lifting to keep their shallow characters from fading away. Arjona remains an increasingly captivating screen presence (she was robbed for an Emmy nod for “Andor”), and there’s always been something more intriguing about Johnson when she’s allowed to be light instead of dark, but both characters are essentially just reflections of their male counterparts’ insecurities. And the end feels truly rushed and kinda silly, even if it also feels inevitable.

It also helps greatly that Covino tapped Newport-Berra to shoot and Sara Shaw to edit these lunatics. The cinematographer turns the lake house into a character, often shooting from a corner of the room to capture how small these people are in all this useless opulence or through a window as chaos unfolds outside. Shaw gives the comedy space to unfold, as seen in an excellent fight scene between Carey and Paul, which allows for time to be sloppy and ridiculous.

On the one hand, “Splitsville” could be written off as another comedy about dumb men. There’s a meta moment near the end in which Braun’s mentalist can predict what the boys in the room are going to say in a movie that’s really about two predictable, man-child protagonists. However, familiarity in comedy isn’t usually a death sentence. There’s a simple question to ask about a film like this one when judging it critically: Did it make you laugh? I did. You’ll know after the first scene.