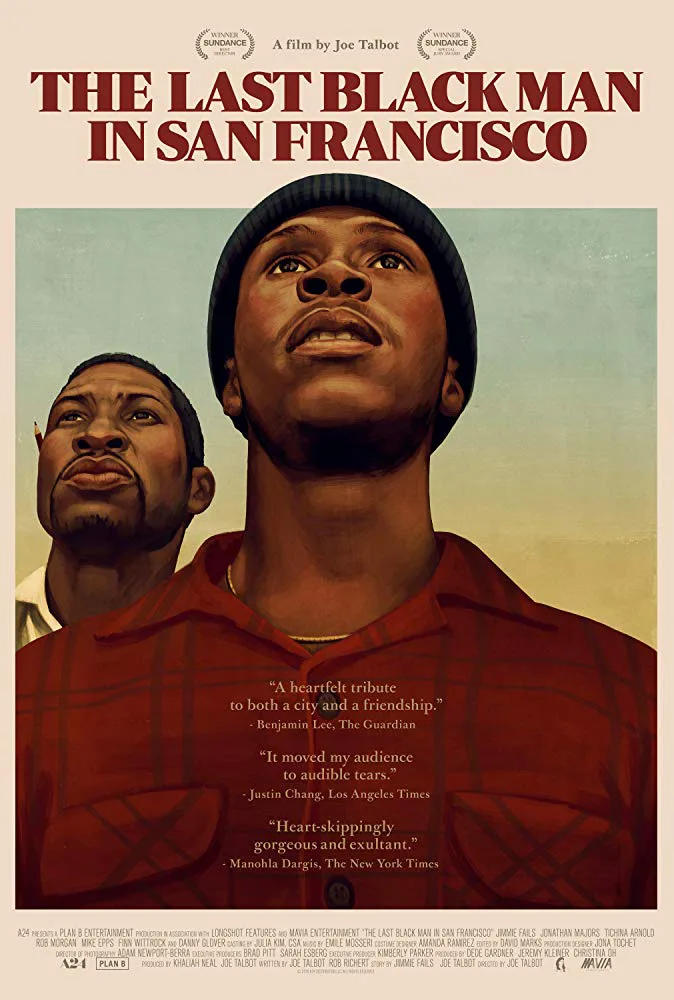

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” is currently streaming on Amazon and Kanopy. #BlackLivesMatter.

There’s a scene in director Joe Talbot’s Sundance winner “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” that you might not buy if you’ve never spent time in the City by the Bay. One of the film’s protagonists sits in a Muni booth awaiting his bus. He is soon joined by an older gentleman who places some sort of protective barrier on the seat before sitting down. The older man is stark naked. Our hero is completely unfazed by this. The two men briefly commiserate on how the city is changing, invaded by outsiders who simply do not get what it means to those born and bred here; these new folks are recasting a beautiful thing in their own ugly image. This won’t be the first time these opinions are expressed on the Muni, but it’s the only time there’s a naked dude in the conversation.

People at my NYC screening laughed at the nudity, treating It as just another odd touch in a film chock full of memorably unusual touches. But my response was a shrug. “Butt nekkid guy—business as usual,” I wrote in my notepad as I flashed back to the numerous instances I was confronted with nonchalant, public male nudity in the Castro. Granted, if you grew up riding the NYC MTA as I did, nothing shocks you anymore. But there was something about the way Talbot and company depicted this scene that felt quintessentially San Franciscan. And while I am not a native nor have I lived there, I have spent hundreds of days in town since 2002. Two weeks from now, I’ll celebrate my 13th anniversary working for a software company located near the Montgomery BART station.

I love San Francisco the way I love Manhattan and my much-maligned home state of New Jersey. So I fell hard for the filmmakers’ use of locations and the overall mise-en-scène. No matter how strange things get—and there’s a wonderful and inviting weirdness throughout—it really feels like you’re in San Francisco. I can only imagine how well this will play in the Bay Area. I was so wrapped up in this movie’s sense of place that when a character mentioned the location of the Victorian house at the center of the story, I wrote it down so I could go see if it were actually there. While there is great acting from legends and newcomers, the real star of “The Last Black Man In San Francisco” is that piece of architecture.

“Weird as it sounds, this movie is a love story about me and a house,” writes Jimmie Fails in the film’s press release. Fails is one of the co-leads, and screenwriters Talbot and Rob Richert based the film on Fails’ life and friendship with Talbot, a relationship that grew from childhood. Talbot spins the tale, expanding it to include sharp commentaries about gentrification, home ownership, toxic masculinity and how Black men are supposed to navigate friendship. But at its core, “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” is a bittersweet romance whose protagonist will go to untold lengths to be with his object of affection. Unlike many tales of amour fou, however, this one is smart enough to consider whether the guy deserves his beloved.

For most of his life, Jimmie (Jimmie Fails) has been squatting in abandoned houses scoped out by his father James Sr. (Rob Morgan). Jimmie is rarely seen without his skateboard, which serves as his main means of transportation, or his best friend Mont (Jonathan Majors). Mont is quite often seen running behind Jimmie as he rides through the neighborhood. Sometimes the two of them ride the board together in a most synchronized fashion, an entertaining sight gag that symbolizes their closeness. At present, Jimmie is crashing at the home of Mont’s grandfather (Danny Glover), sleeping on the floor next to Mont’s bed. Outside the house is a Greek chorus of sorts, a group of men who serve as inspiration for the play Mont is writing. One of those men, Kofi (Jamal Trulove) has a prior history with Jimmie, as they both were stuck in the same group home as teenagers.

The Greek Chorus is one of the threads Talbot will seamlessly weave into the film’s fabric. They’re a bunch of tough-looking brothers who spend endless hours insulting one another. Their games of The Dozens are especially vicious, to the point where one wonders why these guys would want to be around one another. Mont’s observations of them always garner abuse, as does his friendship with Jimmie which, in sharp contrast to the Chorus’ interactions, is exceptionally tender and close. The inseparable friends are subjected to the usual homophobic comments, but they remain unfazed. While the Chorus starts fights with one another, Jimmie and Mont have bigger fish to fry. (Literally, in Mont’s case—one of his jobs is in a fish market.)

Enter the love of Jimmie’s life, a Victorian house in the Fillmore District. The house is unique in that it has a tower whose roof looks like a witch’s hat. Until he was six, Jimmie lived in this house with his father, who inherited it from Jimmie’s grandfather. Jimmie has an even stronger familial tie to the house: in 1946, his grandfather built it with his own two hands. After his father lost the house, it stood abandoned until a couple moved into it, the first of many notes on gentrification that will be played before fadeout. Jimmie, often with Mont’s help, trespasses on the property not to vandalize it vengefully but to repair and contribute to its upkeep. This does not go well with the current residents; the wife throws croissants at Jimmie while the husband whines about how expensive the flying pastries are.

A tragic event leaves the house temporarily abandoned, and that’s when Jimmie makes his move. He takes over the place, using his squatter techniques to build a sanctuary for him and Mont. The attic will serve as the location for the premiere of Mont’s new play, for example, and Jimmie reclaims the secret room he used to hide in back when his parents would argue. This place even has an old pipe organ that bellows dust whenever Jimmie tickles the ivories. As Jimmie points out, this address was the only place he truly felt at home; it was the one stable, static place in a lifetime of wandering uncertainty. It’s easy to understand why he’d fight for it, and why he’d see it with the unrealistic, woozy eyes of someone in love. Its history, at least in the stories Jimmie spins, is the only tangible and reliable thing he has.

I’ve flattened out the plot here. “The Last Black Man In San Francisco” doesn’t move in a conventional sense or even a linear one at times. You have to work for this one, to piece it together and to glean out its messages. Though the film is peppered with familiar faces, from Glover to Mike Epps to the always welcome auntie-based sharpness of Tichina Arnold, Talbot entrusts his directorial debut to his less familiar but equally talented leads. This gives the film a sense of urgency and realism; we’re less star-struck and more awestruck by the plight and emotions of the characters. From scene to scene, we’re unsure where Talbot and his actors are taking us, and even when the destination isn’t surprising, it feels like little else you’ve seen before. There’s a uniqueness to the proceedings that heralds the arrival of a new talent, one unafraid to be brash, sentimental, unabashedly emotional or terrifyingly candid. To see this, one need only look at how Talbot stages the play Mont eventually writes: It quickly morphs into a confession-based memorial service and an intervention, a meta-style commentary on the film’s themes that sears itself into one’s brain.

Talbot and his writers are lifelong San Francisco residents (Talbot is fifth generation), so every frame of “The Last Black Man In San Francisco” is imbued with their love—and their frustration—for the place that made them who they are. Jimmie describes it best during one of the film’s many trips on Muni (some of the best moments in this film unspool from the confines of those grungy buses). After hearing some privileged transplants bitch about how much they can’t stand their new home, Jimmie interrupts them, telling them they don’t have the right to hate San Francisco—they just got here. “You can’t hate something if you didn’t love it first,” he says, summing up yet another of the film’s messages. You haven’t earned the right to be critical of a place unless you’ve paid your dues there, and even then, you’ll miss the old way of life when it’s gone. The poignancy of that thought is right there in the film’s title. Jimmie’s story is a slow ballad, a tragic ode, a dirty limerick, a wistful lament and a heartbreaking elegy. It’s a tribute to the notion of home that we all carry. This is one of the year’s best films.

“The Last Black Man in San Francisco” is currently streaming on Amazon and Kanopy.