If this movie had been directed by someone else, I might have thought differently about it because I might not have expected so much. But “The Color of Money” is directed by Martin Scorsese, the most exciting American director now working, and it is not an exciting film. It doesn’t have the electricity, the wound-up tension, of his best work, and as a result I was too aware of the story marching by.

Scorsese may have thought of this film as a deliberately mainstream work, a conventional film with big names and a popular subject matter; perhaps he did it for that reason. But I believe he has the stubborn soul of an artist, and cannot put his heart where his heart will not go. And his heart, I believe, inclines toward creating new and completely personal stories about characters who have come to life in his imagination – not in finishing someone else’s story, begun 25 years ago.

“The Color of Money” is not a sequel, exactly, but it didn’t start with someone’s fresh inspiration. It continues the story of “Fast Eddie” Felson, the character played by Paul Newman in Robert Rossen’s “The Hustler” (1961). Now 25 years have passed. Eddie still plays pool, but not for money and not with the high-stakes, dangerous kinds of players who drove him from the game. He is a liquor salesman, a successful one, judging by the long, white Cadillac he takes so much pride in. One night, he sees a kid playing pool, and the kid is so good that Eddie’s memories are stirred.

This kid is not simply good, however. He is also, Eddie observes, a “flake,” and that gives him an idea: With Eddie as his coach, this kid could be steered into the world of big-money pool, where his flakiness would throw off the other players. They wouldn’t be inclined to think he was for real. The challenge, obviously, is to train the kid so he can turn his flakiness on and off at will – so he can put the making of money above every other consideration, every other lure and temptation, in the pool hall.

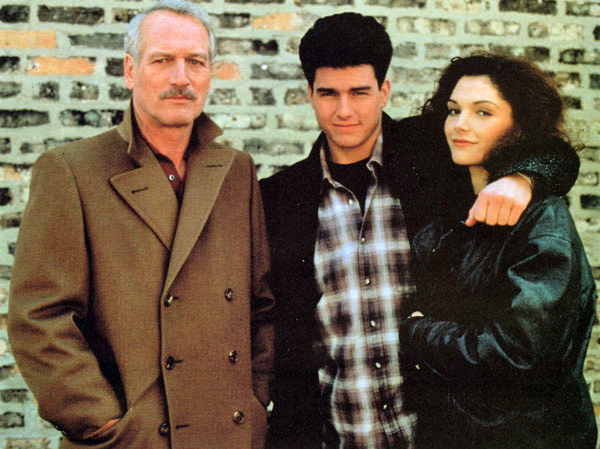

The kid is named Vincent (Tom Cruise), and Eddie approaches him through Vincent’s girlfriend, Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). She is a few years older than Vince and a lot tougher. She likes the excitement of being around Vince and around pool hustling, but Eddie sees she’s getting bored. He figures he can make a deal with the girl; together, they’ll control Vince and steer him in the direction of money.

A lot of the early scenes setting up this situation are very well handled, especially the moments when Eddie uses Carmen to make Vince jealous and undermine his self-confidence. But of course these scenes work well, because they are the part of the story that is closest to Scorsese’s own sensibility. In all of his best movies, we can see this same ambiguity about the role of women, who are viewed as objects of comfort and fear, creatures that his heroes desire and despise themselves for desiring. Think of the heroes of “Mean Streets,” “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull” and their relationships with women, and you sense where the energy is coming from that makes Vincent love Carmen, and distrust her.

The movie seems less at home with the Newman character, perhaps because this character is largely complete when the movie begins. “Fast Eddie” Felson knows who he is, what he thinks, what his values are.

There will be some moments of crisis in the story, as when he allows himself, to his shame, to be hustled at pool. But he is not going to change much during the story, and maybe he’s not even free to change much, since his experiences are largely dictated by the requirements of the plot.

Here we come to the big weakness of “The Color of Money”: It exists in a couple of timeworn genres, and its story is generated out of standard Hollywood situations. First we have the basic story of the old pro and the talented youngster. Then we have the story of the kid who wants to knock the master off the throne. Many of the scenes in this movie are almost formula, despite the energy of Scorsese’s direction and the good performances. They come in the same places we would expect them to come in a movie by anybody else, and they contain the same events.

Eventually, everything points to the ending of the film, which we know will have to be a showdown between Eddie and Vince, between Newman and Cruise. The fact that the movie does not provide that payoff scene is a disappointment. Perhaps Scorsese thought the movie was “really” about the personalities of his two heroes, and that it was unnecessary to show who would win in a showdown. Perhaps, but then why plot the whole story with genre formulas, and only bail out at the end? If you bring a gun onstage in the first act, somebody will have been shot by the third.

The side stories are where the movie really lives. There is a warm, bittersweet relationship between Newman and his long-time girlfriend, a bartender wonderfully played by Helen Shaver. And the greatest energy in the story is generated between Cruise and Mastrantonio – who, with her hard edge and her inbred cynicism, keeps the kid from ever feeling really sure of her. (Mastrantonio, an Oak Park River Forest High graduate, will be in town this weekend for a reunion.) It’s a shame that even the tension of their relationship is allowed to evaporate in the closing scenes, where Cruise and the girl stand side by side and seem to speak from the same mind, as if she were a standard movie girlfriend and not a real original.

Watching Newman is always interesting in this movie. He has been a true star for many years, but sometimes that star quality has been thrown away. Scorsese has always been the kind of director who lets his camera stay on an actor’s face, who looks deeply into them and tries to find the shadings that reveal their originality. In many of Newman’s closeups in this movie, he shows an enormous power, a concentration and focus of his essence as an actor.

Newman, of course, had veto power over who would make this movie (because how could they make it without him?), and his instincts were sound in choosing Scorsese. Maybe the problems started with the story, when Newman or somebody decided that there had to be a young man in the picture; the introduction of the Cruise character opens the door for all of the preordained teacher-pupil cliches, when perhaps they should have just stayed with Newman and let him be at the center of the story.

Then Newman’s character would have been free (as the Robert De Niro characters have been free in other Scorsese films) to follow his passions, hungers, fears and desires wherever they led him – instead of simply following the story down a well-traveled path.