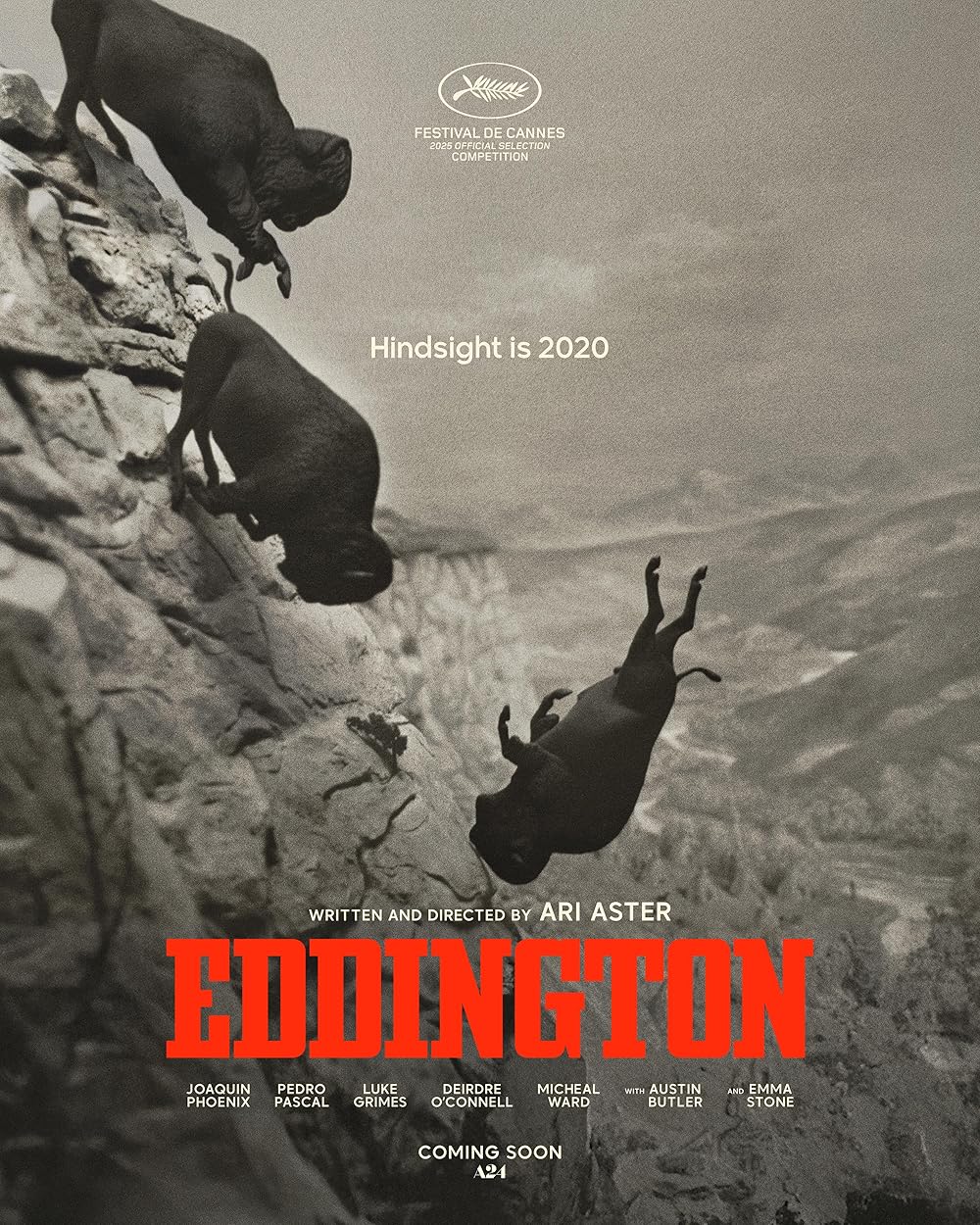

Ari Aster’s “Eddington” is a deliberately hollow provocation. It sets itself up as a statement on the chaos that took place in the summer of 2020, only to conclude that there is no explanation why much of humanity collapsed under the weight of conspiracy theories, mask debates, Black Lives Matter protests, and the rise of viral culture. You want to know how we got here? Tough shit. You never will. No one will.

It’s a challenging film that plays with hot-button ideas, including third-rail topics like racial division, without much of significant interest to say about them … and yet I think that’s the point. Remember all of that anxiety, confusion, division, and mistrust that erupted when people were told to stay home from work or mask up at the grocery store? Aster shoves it all in a blender and hits puree. The result is a film that radically divided critics after its premiere at Cannes and will certainly do the same when people confront it in theaters this summer. There will be some fascinating discussion around this movie, including people who consider its undeniable ambition courageous and those who think its racial provocations downright irresponsible. I think that’s actually how Aster wants it. He’s made a film about divided communities, and he hopes in his own way to do the same to his audience.

This genre-jumping film always returns to its roots as a contemporary Western. A man with a name John Wayne would have approved of, Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), is the world-weary sheriff of the small town of Eddington, New Mexico, population 2,634. It feels like a place on the verge of conflict before 2020 knocked the dominoes over. Aster treats the chaos of that year as the Man in Black in his genre: The stranger who came to town and riled up the locals down at the saloon.

In this case, the watering hole is owned by Mayor Ted Garcia (an effective Pedro Pascal), who has a controversial past with Cross and an increasingly tempestuous present. Garcia’s history with Joe’s wife, Louise (Emma Stone), and mother-in-law, Dawn (Deirdre O’Connell), only adds to the tension that rises when the two men find each other on either side of the mask debate. It really kicks off at a grocery store when Joe defends a local who’s being kicked out for not wearing a mask. After all, no one in Eddington has even gotten COVID yet. And it’s hard to breathe in those things!

Before long, Joe is using anti-masking as a platform to run for Mayor himself, desperately trying to add meaning to his troubled life in some of the most truly pathetic ways. He puts conspiracy theories on the car he drives around town, which gets increasingly ridiculous (and very funny). He’s one of those guys who grasps at anything that might give him a much-needed victory, one of many who saw the chance to take sides in 2020 as a route to much-needed definition of character. It gave idiots personalities they never had before. But politics plays into Joe’s worst tendencies, amplifying his desperation and need. Like a firework thrown into a gas station, Joe’s increasingly irrational behavior feels destined for violence, and you know that the writer/director of “Hereditary,” “Midsommar,” and “Beau is Afraid” isn’t going to pull his punches.

What’s he punching at? Our response to the pandemic is merely the beginning. He opens his film with sound bites of ludicrous conspiracy theories about COVID, many amplified through Dawn’s constant repetition. She prints them out for Louise and Joe and leaves them around the house. Dawn continues the trend in Aster’s work of mothers who only feed the anxiety monsters in their sons (and, in this case, son-in-law). And Louise begins to slide down that hill, drawn to a viral charlatan (Austin Butler) who knows all the buzzwords to get people fired up about literally nothing. Butler’s underwritten role feels like one of several feints in Aster’s script. He’s constantly heading down one road—COVID, BLM, politics, viral conmen, etc.—only to take a hard right down another dusty trail in Eddington to find someone else doing something aggravatingly stupid and increasingly violent.

Aster’s films often have a strong visual language, and that’s the case here, especially in excellent cinematography from the veteran Darius Khondji (“Uncut Gems,” “The Immigrant”) that amplifies both the satire and the tension without drawing focus. Lucian Johnston’s editing is similarly accomplished, keeping a long film humming from one heated encounter to another. And Aster gets consistently strong performances from his cast, reminding us of Phoenix’s excellent comic timing, even if some of the supporting players feel like cogs in the machine instead of actual people. The young people who end up really shaping the violence to come—including characters played by Micheal Ward, Luke Grimes, Cameron Mann, Matt Gomez Hidaka, and William Belleau—start to feel like victims of the plotting in ways that detract from any potential emotional thrust.

A story about law enforcement and division in May 2020 has to include the international response to George Floyd and the protests of that summer, which get all the way to Joe’s doorstep. And here’s where it sometimes feels like Aster’s Western is shooting blanks. Playing with how enraged people got about putting a cloth mask on their face to go to Publix is a little different than using the language around the death of George Floyd for satire. And how Aster uses his non-white characters, especially as the film gets bloody (in ways I can’t unpack without spoiling), starts to feel less like cynicism and more like exploitation. It’s not to say that one can’t take “serious subject matter” and mine it for laughs, but that Aster’s “isn’t this all ridiculous” aesthetic has a different tenor when it starts unpacking race with the same nonchalance with which it’s making fun of Hydroxychloroquine. It’s where the film is really going to divide and aggravate people.

Which I think is what he wants. It’s the mask debate, conspiracy theories, viral culture, the response to the protests, and everything else we raged about filtered through a timeless movie genre, one that itself was often about showdowns between men who considered themselves righteous in towns that never expected to see bloodshed. It’s not just about the divisiveness of 2020; it’s designed to be divisive itself in 2025. To that end, even if you hate it, it’s kind of done its job.

This review was filed from the Cannes Film Festival on May 17th. It opens on July 18th.