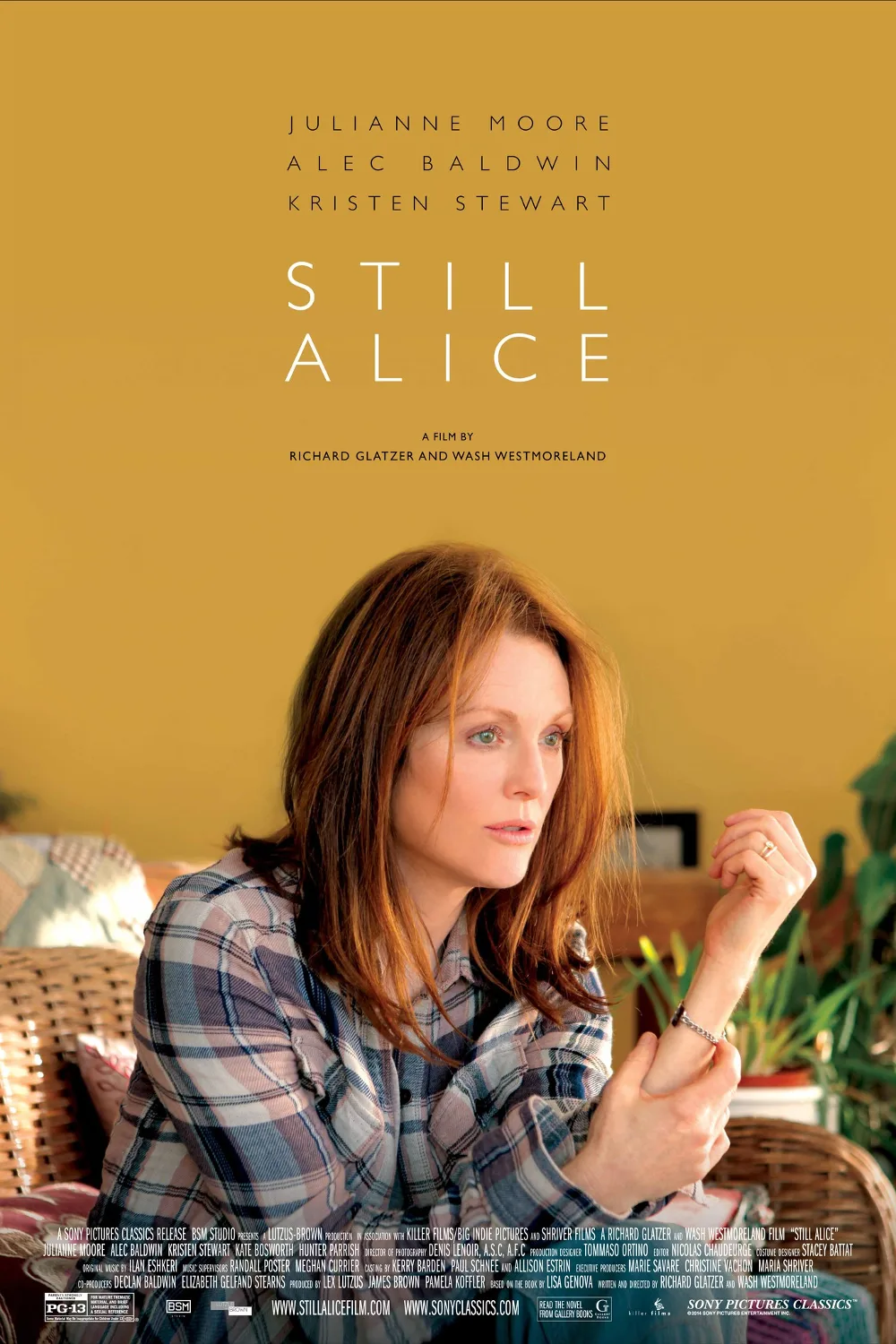

With a combination of power and grace, Julianne Moore elevates “Still Alice” above its made-for-cable-television trappings, and delivers one of the more memorable performances of her career.

This is no small feat, given the depth and breadth of Moore’s filmography and her consistent ability to produce great work, from playing a porn star in “Boogie Nights” to an eccentric artist in “The Big Lebowski” to a frustrated housewife in “Far From Heaven” to her dead-on portrayal of Sarah Palin in HBO’s “Game Change.” She’s such a smart, clever and instinctive actress that she never hits a false note. She finds unexpected avenues into her character, a challenging role that requires her to show a mental deterioration that’s both gradual and inherently internal.

Thankfully, “Still Alice” doesn’t deify the woman she plays: Dr. Alice Howland, an esteemed linguistics professor at Columbia University who finds she’s suffering from early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Co-directors and writers Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland don’t shy away from the steady and terrifying way the disease can take hold of a person and strip away her ability to communicate and connect with the outside world. But they also don’t tell this story with much nuance or artistry in adapting Lisa Genova’s novel.

This is especially true when comparing “Still Alice” to a couple of recent films that have tackled the same territory: Sarah Polley’s haunting “Away From Her” and Michael Haneke’s unflinching “Amour.” The flat lighting, the frequent use of maudlin music, a heavy reliance on medium shots and some awkward cutaways for reactions all contribute to the sensation of watching a rather workmanlike production better suited to the small screen. But the film’s heart is in the right place, and the message matters, and it surely will resonate with the millions of people whose loved ones have suffered from this cruel disease.

At the film’s start, though, Alice has everything. It’s her 50th birthday, and she’s celebrating at a chic New York restaurant with her adoring family. Her husband (Alec Baldwin), who’s also an academic, toasts her as the most beautiful, intelligent person he’s ever known. She’s stylish, accomplished, happy and financially secure. She radiates confidence and competence at all times. But soon, words–which have fascinated her throughout her life and provided the basis for her career–begin to elude her. She becomes disoriented on her daily jog around campus. She starts losing items around the house and forgetting scheduled events.

A visit to a neurologist reveals that Alice has a rare form of Alzheimer’s, and that it’s genetic. Fascinatingly, because she is such an intellectual, she’s been able to play tricks on her brain and find shortcuts to mask her illness. But in no time, the bottom drops out from underneath her, and it’s heartbreaking to watch. Moore plays it small for the most part, conveying fear with her eyes or slight shifts in the tone of her voice, so the moments when her character understandably snaps in panic really stand out in contrast.

The fact that a woman who’s an expert in linguistics has trouble articulating herself may seem like an obvious device, but it also adds to the film’s sense of sadness and frustration, because Alice knows all too well the power of self-expression. “Still Alice” is about how she reacts to her own deterioration–how she constantly reassesses it and figures out how to cope. She doesn’t always do it with quiet dignity, which is refreshing; sometimes she even uses the disease to manipulate those around her or get out of a social occasion she’d rather avoid.

But it’s also about how her family reacts in unexpected ways. Her eldest daughter, Anna (a stiff Kate Bosworth), a prim and perfectly coifed lawyer who married well, doesn’t handle Alice’s illness as well as her free-spirited youngest daughter, Lydia (an excellent Kristen Stewart), who’s moved to Los Angeles with dreams of becoming an actress. (The middle child, a son played by Hunter Parrish, is also on the verge of his own impressive career as a doctor).

Adding to the poignancy is the fact that Glatzer was diagnosed with ALS in 2011 after a decade of making independent films with his partner, Westmoreland, including the 2006 hit “Quinceanera.” Surely, he is all too familiar with the struggle of remaining creative and vital. The fact that this is a personal story, earnestly told and filled with hope, ultimately is what shines through with great clarity.