Paul Thomas Anderson‘s “Boogie Nights” is an epic of the low road, a classic Hollywood story set in the shadows instead of the spotlights but containing the same ingredients: Fame, envy, greed, talent, sex, money. The movie follows a large, colorful and curiously touching cast of characters as they live through a crucial turning point in the adult film industry.

In 1977, when the story opens, porn movies are shot on film and play in theaters, and a director can dream of making one so good that the audience members would want to stay in the theater even after they had achieved what they came for. By 1983, when the story closes, porn has shifted to video and most of the movies are basically just gynecological loops. There is hope, at the outset, that a porno movie could be “artistic,” and less hope at the end.

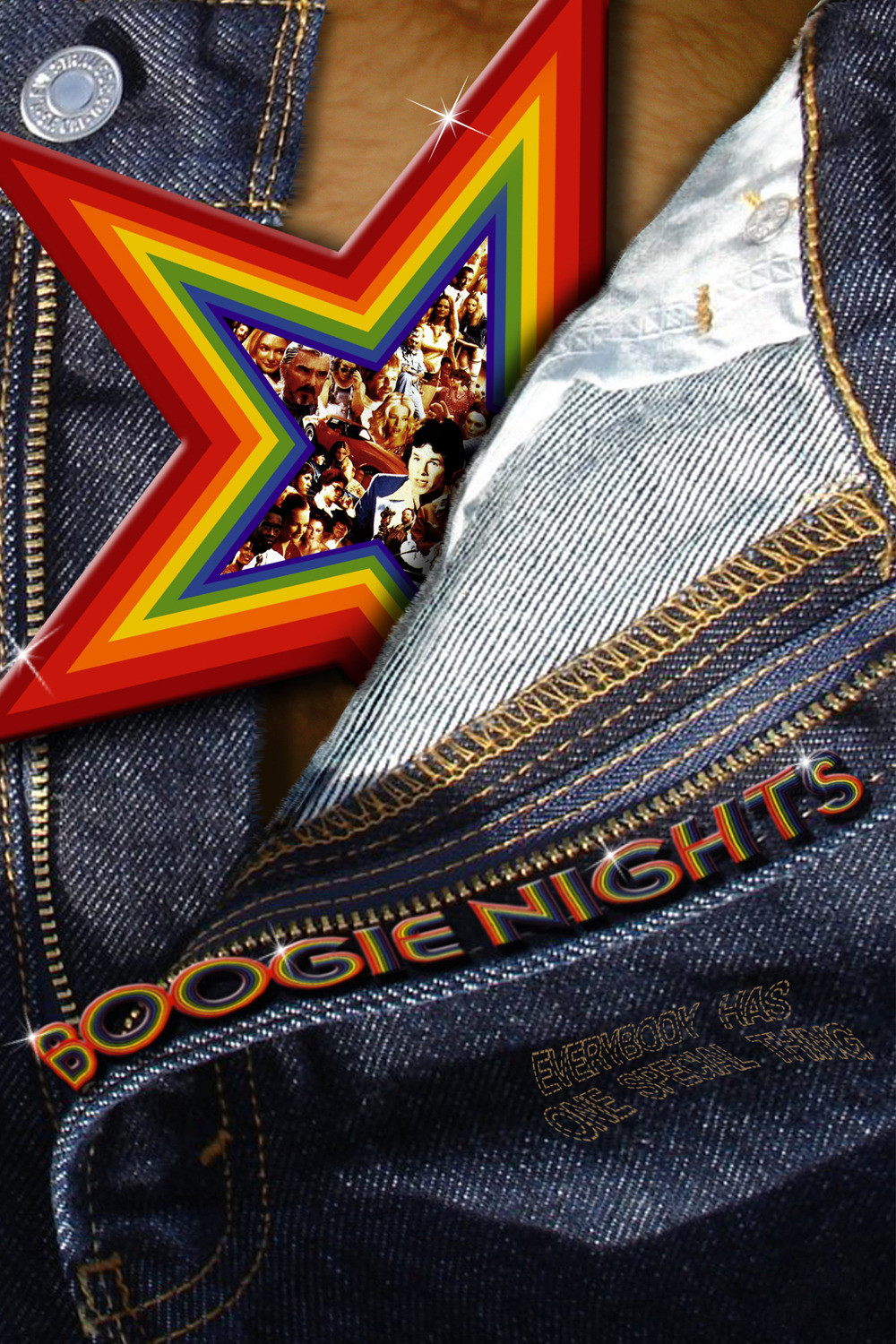

“Boogie Nights” tells this story through the life of a kid named Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg) from the San Fernando Valley, who is a dishwasher in a Hollywood nightclub when he’s discovered by a Tiparillo-smoking pornographer named Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds). “I got a feeling,” Jack says, “that behind those jeans is something wonderful just waiting to get out.” He is correct, and within a few months Eddie has been renamed “Dirk Diggler” and is a rising star of porn films.

If this summary makes the film itself sound a little like porn, it is not. Few films have been more matter-of-fact, even disenchanted, about sexuality. Adult films are a business here, not a dalliance or a pastime, and one of the charms of “Boogie Nights” is the way it shows the everyday backstage humdrum life of porno filmmaking. “You got your camera,” Jack explains to young Eddie. “You got your film, you got your lights, you got your synching, you got your editing, you got your lab. Before you turn around, you’ve spent maybe $25,000 or $30,000.” Jack Horner is the father figure for a strange extended family of sex workers; he’s a low-rent Hugh Hefner, and Burt Reynolds gives one of his best performances as a man who seems to stand outside sex and view it with the detached eye of a judge at a livestock show. Horner is never shown as having sex himself, although he lives with Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), a former housewife and mother, now a porn star who makes tearful midnight calls to her ex-husband, asking to speak to her child. When Jack recruits Eddie to make a movie, Amber becomes his surrogate parent, tenderly solicitous of him as they prepare for his first sex scene.

During a break in that scene, Eddie whispers to Jack, “Please call me Dirk Diggler from now on.” He falls immediately into star mode, and before long is leading a conducted tour of his new house, where his wardrobe is “arranged according to color and designer.” His stardom is based on one remarkable attribute; “everyone is blessed with one special thing,” he tells himself, after his mother has screamed that he’ll always be a bum and a loser.

Anderson wisely limits the nudity in the film, and until the final shot we don’t see what Jack Horner calls “Mr. Torpedo Area.” It’s more fun to approach it the way Anderson does. At a pool party at Jack’s house, Dirk meets the Colonel (Robert Ridgely), who finances the films. “May I see it?” the silver-haired, business-suited Colonel asks. Dirk obliges, and the camera stays on the Colonel’s face as he looks, and a funny, stiff little smile appears; Anderson holds the shot for several seconds, and we get the message.

The large cast of “Boogie Nights” is nicely balanced between human and comic qualities. We meet Rollergirl (Heather Graham), who never takes off her skates, and in an audition scene with Dirk adds a new dimension to the song “Brand New Key.” Little Bill (William H. Macy) is Jack’s assistant director, moping about at parties while his wife (porn star Nina Hartley) gets it on with every man she can. (When he discovers his wife having sex in the driveway, surrounded by an appreciative crowd, she tells him, “Shut up, Bill; you’re embarrassing me.”) Ricky Jay, the magician, plays Jack’s cameraman. “I think every picture should have its own look,” he states solemnly, although the films are shot in a day or two. When he complains, “I got a couple of tough shadows to deal with,” Jack snaps, “There are shadows in life, baby.” Dirk’s new best friend is Reed (John C. Reilly). He gets a crush on Dirk and engages him in gym talk (“How much do you press? Let’s both say at the same time. One, two…”) Buck Swope (Don Cheadle) is a second-tier actor and would-be hi-fi salesman. Rodriguez (Luis Guzman) is a club manager who dreams of being in one of Jack’s movies. And the gray eminence behind the industry, the man who is the Colonel’s boss, is Floyd Gondolli (Philip Baker Hall), who on New Year’s Eve, 1980, breaks the news that videotape holds the future of the porno industry.

The sweep and variety of the characters have brought the movie comparisons to Robert Altman’s “Nashville” and “The Player.” There is also some of the same appeal as “Pulp Fiction,” in scenes that balance precariously between comedy and violence (a brilliant scene near the end has Dirk and friends selling cocaine to a deranged playboy while the customer’s friend throws firecrackers around the room). Through all the characters and all the action, Anderson’s screenplay centers on the human qualities of the players. They may live in a disreputable world, but they have the same ambitions and in a weird way similar values as mainstream Hollywood.

“Boogie Nights” has the quality of many great films, in that it always seems alive. A movie can be very good and yet not draw us in, not involve us in the moment-to-moment sensation of seeing lives as they are lived. As a writer and director, Paul Thomas Anderson is a skilled reporter who fills his screen with understated, authentic details. (In the filming of the first sex scene, for example, the action takes place in an office set that has been built in Jack’s garage. Behind the office door we see old license plates nailed to the wall, and behind one wall of the set, bicycle wheels peek out.) Anderson is in love with his camera, and a bit of a showoff in sequences inspired by the famous nightclub entrance in “GoodFellas,” Robert De Niro’s rehearsal in the mirror in “Raging Bull” and a shot in “I Am Cuba” where the camera follows a woman into a pool.

In examining the business of catering to lust, “Boogie Nights” demystifies its sex (that’s probably one reason it avoided the NC-17 rating). Mainstream movies use sex like porno films do, to turn us on. “Boogie Nights” abandons the illusion that characters are enjoying sex; in a sense, it’s about manufacturing a consumer product. By the time the final shot arrives and we see what made the Colonel stare, there is no longer any shred of illusion that it is anything more than a commodity. And in Dirk Diggler’s most anguished scene, as he shouts at Jack Horner, “I’m ready to shoot my scene RIGHT NOW!” we learn that those who live by the sword can also die by it.