Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull” is a movie about brute force, anger, and grief. It is also, like several of Scorsese’s other movies, about a man’s inability to understand a woman except in terms of the only two roles he knows how to assign her: virgin or whore. There is no room inside the mind of the prizefighter in this movie for the notion that a woman might be a friend, a lover, or a partner. She is only, to begin with, an inaccessible sexual fantasy. And then, after he has possessed her, she becomes tarnished by sex. Insecure in his own manhood, the man becomes obsessed by jealousy — and releases his jealousy in violence.

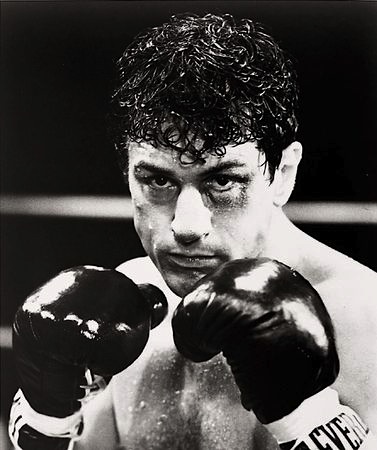

It is a vicious circle. Freud called it the “madonna-whore complex.” Groucho Marx put it somewhat differently: “I wouldn’t belong to any club that would have me as a member.” It amounts to a man having such low self-esteem that he (a) cannot respect a woman who would sleep with him, and (b) is convinced that, given the choice, she would rather be sleeping with someone else. I’m making a point of the way “Raging Bull” equates sexuality and violence because one of the criticisms of this movie is that we never really get to know the central character. I don’t agree with that. I think Scorsese and Robert De Niro do a fearless job of showing us the precise feelings of their central character, the former boxing champion Jake LaMotta.

It is true that the character never tells us what he’s feeling, that he is not introspective, that his dialogue is mostly limited to expressions of desire, fear, hatred, and jealousy. But these very limitations — these stone walls separating the character from the world of ordinary feelings — tell us all we need to know, especially when they’re reflected back at him by the other people in his life. Especially his brother and his wife, Vickie.

“Raging Bull” is based, we are told, on the life of LaMotta, who came out of the slums of the Bronx to become middleweight champion in the 1940s, who made and squandered millions of dollars, who became a pathetic stand-up comedian, and finally spent time in a prison for corrupting the morals of an underage girl. Is this the real LaMotta? We cannot know for sure, though LaMotta was closely involved with the production. What’s perhaps more to the point is that Scorsese and his principal collaborators, actor Robert De Niro and screenwriter Paul Schrader, were attracted to this material. All three seem fascinated by the lives of tortured, violent, guilt-ridden characters; their previous three-way collaboration was the movie “Taxi Driver.”

Scorsese’s very first film, “Who’s That Knocking at My Door?” (1968), starred Harvey Keitel as a kid from Little Italy who fell in love with a girl but could not handle the facts of her previous sexual experience. In its sequel, “Mean Streets” (1973), the same hang-up was explored, as it was in “Taxi Driver,” where the De Niro character’s madonna-whore complex tortured him in sick relationships with an inaccessible, icy blonde, and with a young prostitute. Now the filmmakers have returned to the same ground, in a film deliberately intended to strip away everything but the raw surges of guilt, jealousy, and rage coursing through LaMotta’s extremely limited imagination.

“Raging Bull” remains close to its three basic elements: a man, a woman, and prizefighting. LaMotta is portrayed as a punk kid, stubborn, strong, and narrow. He gets involved in boxing, and he is good at it. He gets married, but his wife seems almost an afterthought. Then one day he sees a girl at a municipal swimming pool and is transfixed by her. The girl is named Vickie, and she is played by Cathy Moriarty as an intriguing mixture of unstudied teenager, self-reliant survivor, and somewhat calculated slut.

LaMotta wins and marries her. Then he becomes consumed by the conviction she is cheating on him. Scorsese finds a way to visually suggest his jealousy: From LaMotta’s point of view, Vickie sometimes floats in slow motion toward another man. The technique fixes the moment in our minds; we share LaMotta’s exaggeration of an innocent event. And we share, too, the LaMotta character’s limited and tragic hang-ups. This man we see is not, I think, supposed to be any more subtle than he seems. He does not have additional “qualities” to share with us. He is an engine driven by his own rage. The equation between his prizefighting and his sexuality is inescapable, and we see the trap he’s in: LaMotta is the victim of base needs and instincts that, in his case, are not accompanied by the insights and maturity necessary for him to cope with them. The raging bull. The poor sap.