History will record the greatness of Michael Collins,” the Irish president and patriot Eamon De Valera said as an old man in 1966, “and it will be recorded at my expense.” Yes, and perhaps justly so, but even Dev could hardly have imagined this film biography of Collins, which portrays De Valera as a weak, mannered, sniveling prima donna whose grandstanding led to decades of unnecessary bloodshed in, and over, Ireland.

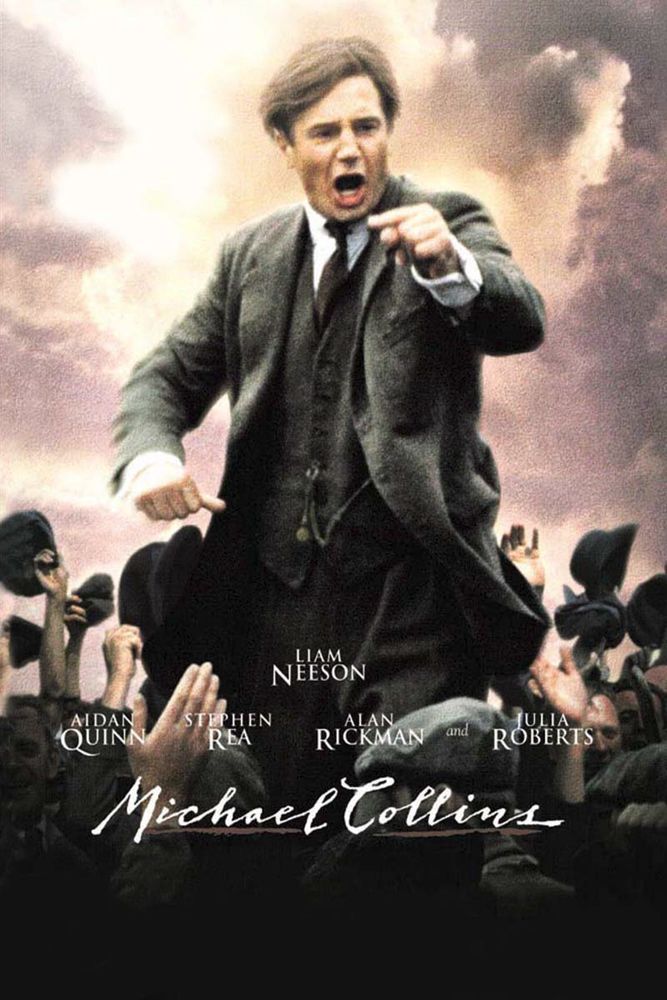

“Michael Collins” paints a heroic picture of the Irish Republican Army’s inspired strategist and military leader, who fought the British Empire to a standstill and invented the techniques of urban guerrilla warfare that shaped revolutionary struggles all over the world. Played by Liam Neeson in a performance charged with zest and conviction, Collins comes across as a clear-sighted innovator who took the IRA as far as it could reasonably hope to go, and then signed a treaty with the British that was, he argued “the best we can hope for at this moment in time.” The treaty established an Irish Free State, but it preserved the division of Ireland into north and south, and it fell short of the independent republic the IRA had been fighting for. Collins felt that additional negotiations over a period of years could eventually produce those gains; he and his comrades were weary of bloodshed.

But De Valera (played with shifty conceit by Alan Rickman) refused to support the treaty, and his decision led to an Irish civil war and, indirectly, to the assassination of Collins. And today IRA bomb blasts still rock London, and the peace that Collins hoped for has come only from time to time.

Was De Valera (who led Ireland in various offices for most of the years between 1932 and 1973) really responsible for all these tragic consequences? Some argue so, but others will find that “Michael Collins,” in need of an Irish villain to balance the British enemy and explain the death of Collins, makes Dev into a weaker and more devious man than he was. The film even implies, without quite saying so, that Dev was aware of, or at least not adverse to, the plot against Collins.

Such questions will be much debated in Ireland, where the minutiae of IRA politics and strategy are a cottage industry. For audiences elsewhere in the world, the facts in “Michael Collins” will be less interesting than the characters and the myths, and on that basis Neil Jordan’s movie functions well, giving us a folk hero known throughout Ireland as “The Big Fella,” who even with a price of 10,000 pounds on his head was able to bicycle through Dublin with impunity.

Partly that was because no one knew, until he went to London to negotiate the peace treaty, quite what Michael Collins looked like. There is a scene in the movie where Collins audaciously presents himself at midnight to British Army headquarters, says he is an informer, gains entrance, and works with an insider (Stephen Rea) to copy secret information on British security forces.

The film, which has the look and feel of authenticity, opens with a one-sided British victory over IRA troops that tried to occupy Dublin’s main post office. Collins sees, correctly, that if the IRA adopts conventional tactics, it will be destroyed by the British troops, and so he argues for a strategy in which IRA men melt into the crowds, are indistinguishable from civilians, and disappear after sudden strikes. This approach is good enough to force the British to the negotiating table (despite the intransigence of Winston Churchill), even though De Valera continues to argue for more conventional methods; he seems to feel diminished by not leading a proper-looking army.

The movie moves confidently when it focuses on Collins and his best friend and co-strategist Harry Boland (Aidan Quinn). But it falters with the unnecessary character of Kitty Kiernan (Julia Roberts), who is in love with both men, and they with her. “I was ahead by a length,” Harry tells her in one scene. “Now where am I?” She shakes her head: “It’s not a race, Harry. You without him…him without you…I can’t imagine it.” The movie uses the scenes with Kitty to provide obligatory romantic interludes between war and strategy, but even though Kitty was a historical character, we never feel the scenes are necessary; they function as a sop to the audience, not as additional drama.

Collins, who died at 31, was arguably the key figure in the struggles that led to the separation of Ireland and Britain. He was also, on the basis of this film, a man able to use violence without becoming intoxicated by it. The film argues that if he had prevailed Ireland might eventually have been united, and many lives might have been saved. We will never know. But De Valera was right. History has judged Collins at his expense.