Charlie Kaufman‘s screenplay for “Adaptation.” (2002) has it three ways. It is wickedly playful in its construction, it gets the story told, and it doubles back and kids itself. There is also the sense that to some degree it’s true: that it records the torments of a screenwriter who doesn’t know how the hell to write a movie about orchids. And it has the audacity to introduce characters we know are based on real people and has them do shocking things.

Even the DVD maintains the illusion of life colliding with art. The case contains a Columbia interoffice memo, seemingly included by accident, not even referring to this movie. And it is startling to see an ant crawling across the main menu until you get to the dialogue line, “I wish I were an ant.”

The movie is the second collaboration between Kaufman and director Spike Jonze, after the equally brilliant “Being John Malkovich” (1999). Jonze spends most of his time making music videos and documentaries, but when he makes a movie, it’s a spellbinder, and he has the serene confidence to wade into this Kaufman screenplay and know that he can pull it off.

The movie is inspired by The Orchid Thief, by Susan Orlean, a best seller expanded from an article in the New Yorker. It involves mankind’s fascination for these extraordinary flowers, the blood that has been spilled in collecting them, their boundless illustration of Darwin’s ideas about natural selection and a contemporary orchid hunter in Florida who is a strange, compelling man. Considered simply like that, the book might have inspired a National Geographic special.

It could also have been a straight fiction film about the life and times of John Laroche, a Miami eccentric who hit upon the idea of collecting endangered species of orchids from swampland that was Seminole territory. By using real Seminoles to obtain his specimens, he exploited their legal right to use their own ancestral lands. Laroche himself is a student of orchids, and he narrates a poetic passage about the limitless shapes that orchids can take in attracting insects — imitating their shapes and coloring, while all the while neither the flower nor the insect realizes what is happening. There is even one orchid so strangely shaped that Darwin hypothesized a moth with a 12-inch proboscis that could dip down into its long, hollow tube. Such a moth was actually found.

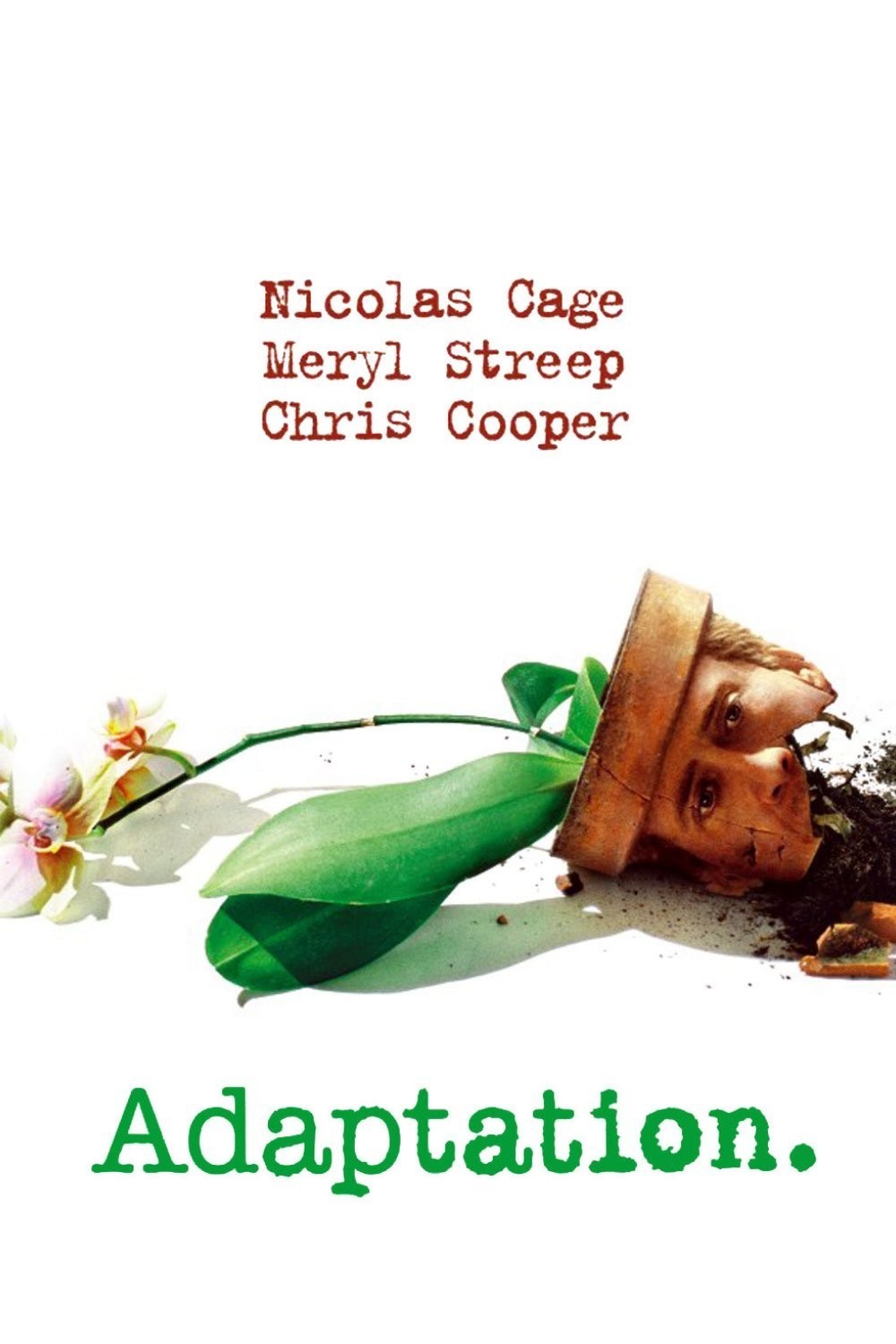

So you see how the movie could have been a doc. But the title is a pun, referring both to Darwinian principle of adaptation and the ordeal of adapting a book into a screenplay. Although its soul is comic, and it indulges in shameless invention, it is also the most accurate film I have seen about this process — exaggerated, yes, but true. We meet Charlie Kaufman and his (fictitious) twin brother Donald, both played by Nicolas Cage, who finds subtle ways so that we can always tell them apart. They’re like the twins in the old joke, one pessimistic, one optimistic (“There must be a pony in here somewhere”).

The movie opens with Charlie’s voiceover cataloging his flaws: He’s too fat, balding, needs exercise, has no talent, etc. So inspired is Donald by his brother’s struggle that he decides to write one of his own, after taking the famous screenwriting seminars of Robert McKee (Brian Cox). Charlie has only scorn for McKee and great doubts about Donald’s story idea, which involves a madman and a woman who are the same person with multiple personalities. But how, asks Charlie, do you put them in the same scene together, when one has the other locked in the basement?

Charlie sweats blood over his screenplay. His copy of the book is thick with Post-It notes, the text painted with yellow and red high-lighters. He has highlighted about everything. In a sneaky way, a good part of the movie is just Charlie reading the book to us. Then he develops an erotic fixation with the author Susan (Meryl Streep), masturbating while imagining her bending tenderly to administer to him. He even flies to New York to meet her, but is paralyzed with shyness.

The third major character is John Laroche (Oscar winner Chris Cooper), a swamp rat with no front teeth, who lives at home with his dad and describes himself as “probably the most brilliant man I know.” At one time, he tells Susan, he had the largest collection of Dutch mirrors in the world. At another, he had a rare collection of tropical fish. He is the only man he knows who can breed the rare Ghost Orchid under glass. When he tires of an obsession, he drops it cold. “Finished with fish,” he says, and in context, it’s one of the movie’s funniest lines.

Having placed these characters onstage (as well as a studio executive played by Tilda Swinton, an agent played by Jay Tavare and various Indians and park rangers), Kaufman intercuts their scenes with scenes of himself creating them, and scenes from a McKee story conference. He lists all the things he hates in blockbusters: the chase, the shootings, the sex.

And now I must tread carefully, so as not to spoil surprises (everything I’ve described so far is just the setup). Without going into details, what Kaufman does is create scenes that merge fact with his creative despair, his erotic imagination and the very kinds of scenes he loathes. Some of these scenes are possibly libelous. The real Orlean and Laroche must have signed waivers abandoning every possible legal recourse; they were very good sports. The scenes are also wildly audacious and hilarious, and you have the instinct that a few of them, such as Laroche driving Orlean in his van and taking her into the swamp, are “based on” truth. That’s quite a van, by the way; it not only smells like things are growing in it, but they are.

I will observe that the final chapter on the DVD menu is titled “Deus Ex Machina.” Wikipedia splendidly explains the term: “improbable contrivance in a story characterized by a sudden unexpected solution to a seemingly intractable problem.” That is exactly what it is, writing Kaufman out of an impossible hole by violating all of his standards.

The performances are wonderful. When Streep’s character ingests an obscure Indian drug, wriggles her toes and does a phone-tone duet with Laroche, you wonder what other actress could have done it so well. Watch Swinton’s studio executive closely during her first luncheon with Charlie. As he describes his grandiose and inflamed ideas, she ties to smile twice, in rapid succession, both smiles breaking down into doubts. Body movements very small, very perfect. Cooper pulls off the feat of making a repulsive character into a plausible romantic object for the author, because of Laroche’s brilliance and enthusiasm. At first sight, he would rank last on any list of lovers for an elegant New Yorker writer.

And Cage. There are often lists of the great living male movie stars: De Niro, Nicholson and Pacino, usually. How often do you see the name of Nicolas Cage? He should always be up there. He’s daring and fearless in his choice of roles, and unafraid to crawl out on a limb, saw it off and remain suspended in air. No one else can project inner trembling so effectively. Recall the opening scenes in “Leaving Las Vegas.” See him in Scorsese’s “Bringing Out the Dead.” Think of the title character in “The Weather Man.” Watch him melting down in “Adaptation.” And then remember that he can also do a parachuting Elvis impersonator (“Honeymoon in Vegas“), a wild rock ‘n’ roller (“Wild at Heart“), a lovesick one-handed baker (“Moonstruck“), a straight-arrow Secret Service agent (“Guarding Tess“) and on and on.

He alway seems so earnest. However improbable his character, he never winks at the audience. He is committed to the character with every atom and plays him as if he were him. His success in making Charlie Kaufman a neurotic mess and Donald Kaufman a carefree success story, in the same movie, comes largely from this gift. There are slight cosmetic differences between the two: Charlie usually needs a shave, Donald has a little more hair. But the real reason we can tell the twins apart, even when they’re in the same trick shot, comes from within: Cage can tell them apart. He is always Charlie when he plays Charlie, always Donald when he plays Donald. Look and see.