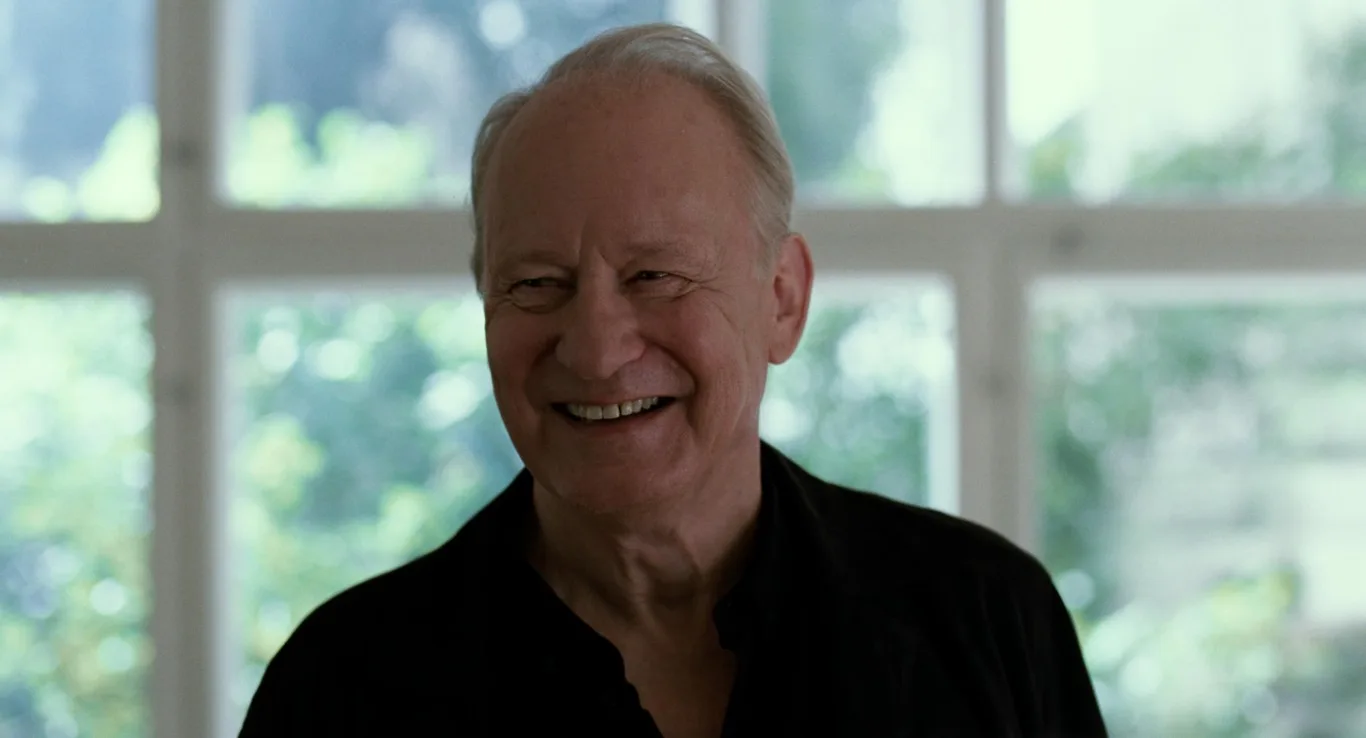

In Joachim Trier’s “Sentimental Value,” a once-revered Norwegian filmmaker struggles to mount a deeply personal project about his family history, going so far as to enlist his estranged daughters—in defiance of their wishes—to help realize his vision.

For Stellan Skarsgård, playing the filmmaker in question, Gustav Borg, was a uniquely rich opportunity; as his character grapples with the decades of distance from his daughters Nora and Agnes, both played with exquisite depth of feeling by Renate Reinsve and Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, he responds at first to their grief and resentment by avoiding it.

Instead, he proceeds with a new film about the death of his mother in the family home, where he intends to shoot it, even utilizing the office where she took her own life. Nora, his eldest daughter, is unwilling to play the lead role, so Gustav instead casts Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), an American ingénue he encounters at the Deauville American Film Festival, during a retrospective series screening the work—intensely emotional wartime dramas—that cemented his reputation as a European auteur.

In Trier’s film (now in theaters), the relationship between Gustav and Rachel, developing in unexpected directions as they work together to excavate the character he’s written, becomes a profound exploration of the strange, intimate alchemy that can occur between actors and directors, even as it also reflects Gustav’s struggle to reconnect with the daughters he once walked out on.

Trier never had any actor in mind besides Skarsgård for the lead role; desperate to cast him, he flew to Sweden and reportedly begged him to take the part. Sensing that the role would stretch his considerable range, the actor agreed. Fanning, meanwhile, came to Trier’s attention after a recommendation from Mike Mills, who’d worked with the actress in “20th Century Women.” An American actress in a Norwegian production, Fanning added a metatextual layer to the story through her very presence. Still, that self-awareness compelled her to disappear further into the role of an actress, lost in her career, desperate to experience more from the film industry than it has given her.

Taking a break from production on “Predator: Badlands” in New Zealand, Fanning flew to Oslo to rehearse with Skarsgård over a long weekend, where the two worked with Trier to mold their characters to better reflect their understanding of the roles. Between her commitments to the sci-fi “Predator” franchise, she flew directly to Deauville to film her scenes there before continuing on to Oslo, where the actors further honed their collaboration.

With “Sentimental Value” now in theaters, Fanning and Skarsgård reflected on the unusual depth of their on-screen dynamic, the filmmakers who’ve made them feel truly seen, their favorite moments working together, and much more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This is such a delicate story. How did you find the connection between your characters—this young actress and this reclusive director—and the strange intimacy that grows between them?

Stellan Skarsgård: We’re actors, and actors do create an enormous intimacy—and a real intimacy—in seconds. But it only lasts for three months, and then it’s gone. [laughs] The intimacy was not a problem, and Elle is a fantastic woman, so it was easy to relate to her and play with her.

Elle Fanning: We’re both child actors, so we have that in common. We also started filming in Deauville, so the beach scenes where Gustav and Rachel meet for the first time were our first scenes together, which I think was a perfect starting point for our characters, to have that kind of spark and connection happen, then get to create from there. Like Stellan said, actors all speak the same language, and with a script this good and Joachim leading the charge, he cultivated that for us.

I’m curious what starting in Deauville and filming scenes set at a film festival added for you, in terms of the meta elements of making a film set in the world of acting, which is so often relevant to your lives outside specific roles.

EF: We filmed during the film festival, while it was happening, with everything bustling around us. We had night shoots, and it was very cold in Deauville. As an actor, I’m normally not used to shooting my first scene on the first day or my last scene on the last day, because I’m used to shooting out of chronological order. But I do think starting in Deauville was helpful in that sense.

I also got to watch the movie that Gustav made, the clip of the film that Joachim actually shot; I got to watch that in real time in a theater, and it really struck me—because it’s very good. The girl is so good, and it shows that Gustav is an amazing director, you know. Almost in those moments, Rachel becomes a surrogate daughter. He’s able to open up to her and work with her in this artistic way that he can’t do in reality with his own children.

Rachel is definitely searching and longing for purpose; Gustav sees that in her. She feels almost like the light has shone on her; it’s something she’s wanted. She’s wanted an opportunity to showcase her talents, so she makes a bold decision to really go with him after their time at the beach, where they share a connection.

I always felt like Rachel probably hadn’t had that director-actor connection in that way before; that feeling is a really special feeling, and I have gotten to feel that before, and I certainly felt that with Joachim, but we were trying to capture that.

SS: We started lighthearted. The scenes in Deauville don’t really continue, in a way. They’re standalone, like film festivals are. It’s a short party in the world of reality—and they’re irresponsible. Gustav has had a scene rejected by his daughter before, so he’s down memory lane. He sees this retrospective of his films and meets this young, vibrant actress; he’s just enjoying it. He thinks he’s finished as a director, actually, and there’s a sad undertone to it, but that doesn’t affect his joy of spending the night with her.

In your careers as actors, when were the first times you remember feeling that type of intimate bond with a director, the sense of another artist really seeing you?

EF: I mean, I’ve been lucky. I’ve had it quite a few times, but also at different ages. I think the ages really matter, too—because it’s about at what age you need a certain thing. I worked with Sofia Coppola when I was 11, and she saw me. She was this cool aunt who took me under her wing, valued my opinions, and didn’t talk down to me. That was something special.

I definitely can pinpoint a lot of people who have done that—certainly, with Joachim, it was a profound experience. He really sees his actors, and he has to—it’s the magic ingredient of what makes his films work so well, the minutiae of our faces, the small mannerisms and expressions. He’s able to capture those because he creates a safe environment where you want to feel vulnerable, express, and be open. He encourages us to be spontaneous in a way, to react completely. He’s not afraid of silence, and you can see that in the movie. That’s my favorite type of directing. Now that I’ve worked with Joachim, I’m like, “Well… Can I go back?”

SS: I mean, there’s one director that I’ve worked with a lot in my life, who’s Hans Petter Moland, and we’ve collaborated on very different kinds of films. We’ve even been to the Arctic, and we’ve had a lot of fun together. Another collaborator is Lars von Trier, of course—the other Trier. He’s been so special and wonderful.

What they have in common, those directors, is that—in the case of all three of them—the set is a safe place. You can do anything on the set, and you’re not a tool; really, you’re a source of inspiration. You’re supposed to produce a mess of expressions, of different temperatures, which will lead the director to a lot of options when he fine-tunes it in the end and edits it.

There’s a heartbreaking honesty to so many of the conversations that your characters have, especially in the latter half of the film, around that idea of being potentially miscast, or realizing that you might not be on the same page in terms of your vision of a character, your place within a film that you’re working on. What were you able to bring into that part of the narrative, being actors with a great deal of experience? I imagine you’ve had to navigate that confusion before, in some way.

EF: It’s the heartbreaking element to Rachel: she’s so desperate for something that she’s miscast for, but she’s trying to find her way in. She starts to realize, over time, that being amongst the family drama reveals the cracks and gives her immense empathy—to understand, possibly, where Gustav is coming from. But it is at the cost of what she wants, so she learns something. She’s very invested in the outcome of her career, in pushing forward, but over time in the film, she has to realize that it’s really about the experience and the journey she has.

Gustav awakens something in her; she later feels she does have the confidence and the talent, but ultimately knows, “I will walk away from this, but I will keep this experience with me, and that will make me a better actor and a better person.” There are personal things, for sure, that I can relate to in this—and, on a surface level, sometimes when you’re talking about a character with the director, you’re like, “Oh, we just see it so differently.” It can be a very confusing state to be in when you want to do a good job.

Rachel quickly learns it’s not her; it’s his own demons that he’s facing, but he can’t say that. He doesn’t know how to say it. He keeps saying, “Well, it’s not about my mother,” because it’s really about his daughter. She comes to learn this, then does a courageous thing by walking away. But that changes her for the better.

SS: It’s a very important scene for me as Gustav, what we’re talking about, because it’s the first time he realizes it. He listens to her, and he hears her, and he realizes that maybe he wasn’t right. He’s been trying to project somebody else—his daughter, for instance—into this film, onto her. He says the one line: “I’ve let you down, and I’m sorry.” He sincerely means it. Gustav has little dialogue; Elle keeps the scene going, but his reaction to her—to her devastation—is wonderful to see, and it’s wonderful to play.

Elle, one of my favorite lines of dialogue in this film is one you say to Renate’s character, in discussing your struggle to understand your character: “The more that I study her, the more lost I feel trying to be her. It’s like her sadness is… It’s such an overwhelming part of her. It’s a beautiful theme. But I can’t tell if that’s just the cause or everything, or is it… a symptom of something deeper.” It’s a beautiful sentiment, in part because it gives us a sense of how Rachel approaches her process of understanding, of getting into her character. Tell me about finding your way into a form of the creative process that would be honest to your characters.

SS: It was crucial to find out what kind of director he was. What made it interesting, for me, is that he had to be an extremely sensitive director and an expert on expressing feelings in his words—as bad as he is in his private life, right? I’ve met several directors who are like that. They’re masters at expressing and explaining human feelings in their filmmaking, and they just can’t handle it in their personal lives. Sometimes, it’s because the film work is an escape from reality for them, because it is manageable. That was my take on it. Of course, I did not want to have any residual feeling of cynicism. When I go with Rachel, I go fully with her as an actress. I don’t know that I am trying to make her be my daughter.

EF: For Rachel, with that, she’s not used to working in that way. I think she’s interested in the results. She’s academic when it comes to acting; she’s technical, and she has these big feelings inside of her, but doesn’t know exactly how to portray them on screen. I mean, this is just something that I thought about. She’s like, “Okay, I know my lines, I’ve annotated this, I’ve done my homework,” but she hasn’t found that spontaneity.

During the rehearsal, when she reads the monologue Gustav wrote, something really awakens in her. It takes her by surprise. I’ve had those moments before: of feeling like you’re on a set, but the emotion just comes, and it’s exhilarating. Normally, it’s caught on camera, although not necessarily in a rehearsal—but for Rachel, it’s a discovery in that rehearsal that she can go to those places. I think her relationship to her work really changes over the course of that scene, which was fascinating to play, because of that emotion. She’s very excited and giddy that she was able to have that.

Would each of you be able to share a memory that you look back on: whether with the experience of working with one another on this project, or with some moment where you felt like this project was enriching you as a performer?

SS: I think that was our final scene together. It moved me, in a real way, when it ended. It lingered, too. It’s something I could not process at the moment, but I experienced it. Elle was fantastic there.

EF: Thank you, Stellan. That was that day. That was a really special day. It was the culmination of the whole experience. For my character, it’s kind of her end, where he sends her off, and it was a very charged day. I think I came in with a lot of thoughts and emotions, and it took me to different places—but, always, I was looking into Stellan’s eyes.

For me, in Deauville, on the beach, there were a lot of dreamlike moments, where Joachim would say—without saying we were ad-libbing—that we could say what we wanted to say. It was about looking into Stellan’s eyes; playing this character, I found myself getting emotional and moved by completely seeing Gustav’s inner life: the devastation he had felt, that he didn’t know he was feeling, about the rejection from his daughter. All of that was completely there. It’s not necessarily in the lines, but it’s not acting anymore, at that moment, and that was special for me, being taken on that journey.

“Sentimental Value” is now in theaters, via Neon.