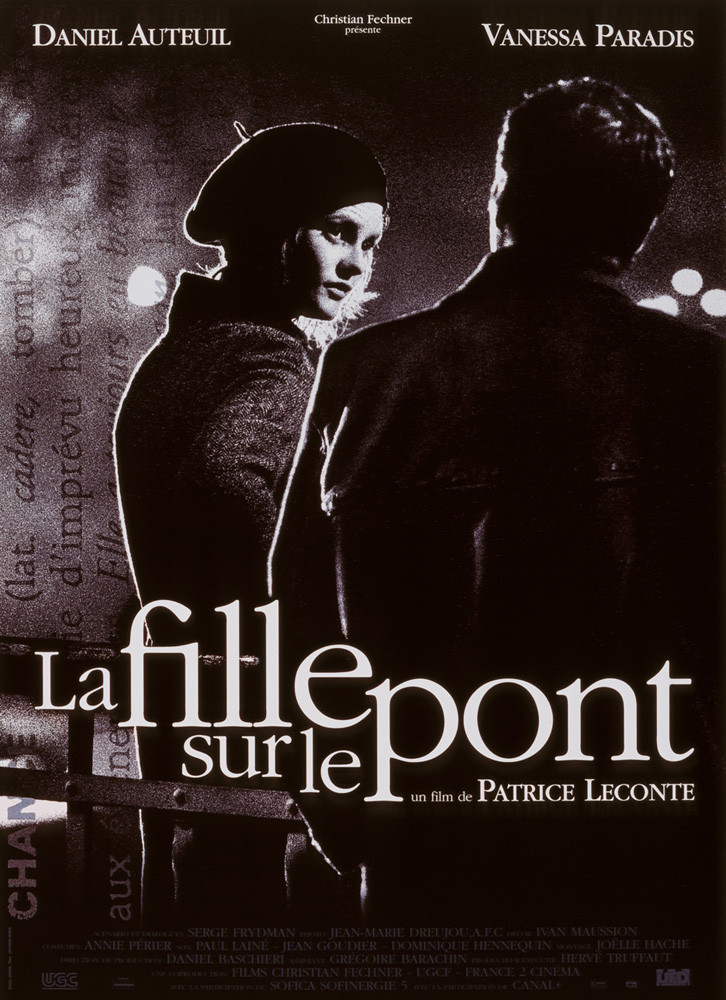

The hero of “Girl on the Bridge” hangs around bridges in Paris, looking for girls who are about to jump. Then he offers them a deal. Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem, so perhaps they will consider working for him. He is a knife-thrower. There is always the possibility he will miss. If he doesn’t, they get an interesting job with lots of travel. If he does hit them, well, what do they have to lose? This logic proves persuasive to Adele (Vanessa Paradis), who signs on with Gabor (Daniel Auteuil). Well, not immediately; first she jumps, or perhaps slips, into the water, and he has to jump in and save her life. That will get a girl’s attention. They travel from one venue to another, at first in the south of France, as he straps her to a cork backdrop and hurls knives at her. There are variations. He straps her to a spinning wheel. Sometimes he is blindfolded, or she is concealed beneath a sheet. They are booked on cruise ships, where the rocking of the waves adds a risk factor.

Gabor complains that his eyes are failing him (“Past 40, knife-throwing becomes erratic”), but he is really very good, a skill revealed by the fact that this film is not a short subject. If he is good at knives, she is good at roulette, and in the casinos in the towns where they appear, she has an extraordinary run of good luck. His luck has turned good, too; they’re making better money, finding better bookings, and they become so closely in sync they can even hear each other’s thoughts.

“Girl on the Bridge” was directed by Patrice Leconte, a French filmmaker whose work includes “Monsieur Hire” (1989), “The Hairdresser's Husband” (1990) and “Ridicule” (1996). He is fascinated by the hoops that his characters will jump through in their search for sexual fulfillment. Monsieur Hire is a bald little man of solemn visage who is a voyeur. He meekly worships the woman in the apartment across the way, who is not oblivious to his attentions, but his haplessness is his undoing. “The Hairdresser’s Husband,” however, is about a man who became fixated in adolescence on hairdressers and wants to be present only while the woman of his dreams cuts hair. Now comes the knife-thrower.

Leconte’s movies almost always involve a deep, droll humor (it is hard to see in “Monsieur Hire,” but it is there). He’s amused by human nature. His characters in “Girl on the Bridge” aren’t oblivious to the humor in their situation; their love and luck seem to depend on earning their living by seeing how close they can come to disaster. Much of their appeal comes from the human qualities of the performers. Auteuil, he of the crooked nose and mournful countenance, is a man who can hardly believe good fortune, and Paradis is a woman who can see that during many of her orgasms the joke is on her.

The movie begins by taking an absurd situation rather seriously and then lets the seriousness melt away; by the time the lovers have voluntarily gotten themselves into a rowboat in the middle of the ocean, we are almost in Looney Tunes territory.

Leconte’s own adolescent fixation seems to be with exotic Turkish harem music, which he gets around to with amazing frequency in his movies. In “The Hairdresser’s Husband,” so great was the husband’s exuberance that he would sometimes put Turkish music on the phonograph and dance about the shop. In “Girl on the Bridge,” the lovers work through the French and Italian Rivieras and then move on by sea to Istanbul–perhaps for no better reason than so Leconte can slip his favorite music onto the soundtrack.

What’s best about the movie is its playfulness. Occupations like knife-throwing were not uncommon in silent comedy, but modern movies have become depressingly mired in ordinary lifestyles. In many new romantic comedies, the occupations of the characters don’t even matter, because they are only labels; there’s a setup scene in an office, and everything else is after hours. Here, knife-throwing explains not only the man’s desperation to meet the woman, but also the kind of woman he meets, and the way they eventually feel about each other. Dr. Johnson once said that the knowledge that you will be hanged in the morning concentrates the mind wonderfully. There is nothing like being partners in a knife-throwing act to encourage a man and a woman to focus on their relationship.