Darwin, it is generally agreed, had the most important idea in the history of science. Thinkers had been feeling their way toward it for decades, but it took Darwin to begin with an evident truth and arrive at its evident conclusion: Over the passage of many years, more successful organisms survive better than the less successful. The result is the improvement of future generations. This process he called “natural selection.”

It worked for bugs, birds and bees. It worked for plants, fish and trees. In 1859, when he published On the Origin of Species, it explained a great many things. Later, we would discover it even explained the workings of the cosmos. But — and here was the question even Darwin himself hesitated to ask — did it explain Man?

Emma Darwin, his wife, didn’t think so. She was a committed Christian who believed with her church that God alone was the author of Man. And for her it wasn’t God as a general concept, but the specific God of Genesis, and he created Man exactly as the Old Testament said he did. He did it fairly recently, too, no matter that Darwin’s fossils seemed to indicate otherwise.

“Creation” is a film about the way this disagreement played out in Darwin’s marriage. Charles and Emma were married from 1830 until his death in 1882. They had 10 children, seven of whom survived to beget descendants who even today have reunions. They loved one another greatly. Darwin at first avoided spelling out the implications for Man in the Theory of Evolution so as not to disturb her. But his readers could draw the obvious conclusion, and so could Emma: If God created Man, he did it in the way Darwin discovered, and not in the way a 4,000-year-old legend prescribed.

The problems this created in the Darwin marriage were of interest primarily to Emma and Charles, probably their children, and few others except in the movie business, which seldom encounters an idea it can’t dramatize in terms of romance. It helps to know going in that “Creation” will give you an idea of the lives and times of the Darwins, but unless you bring your knowledge of evolution to the movie, you may not leave with much of one.

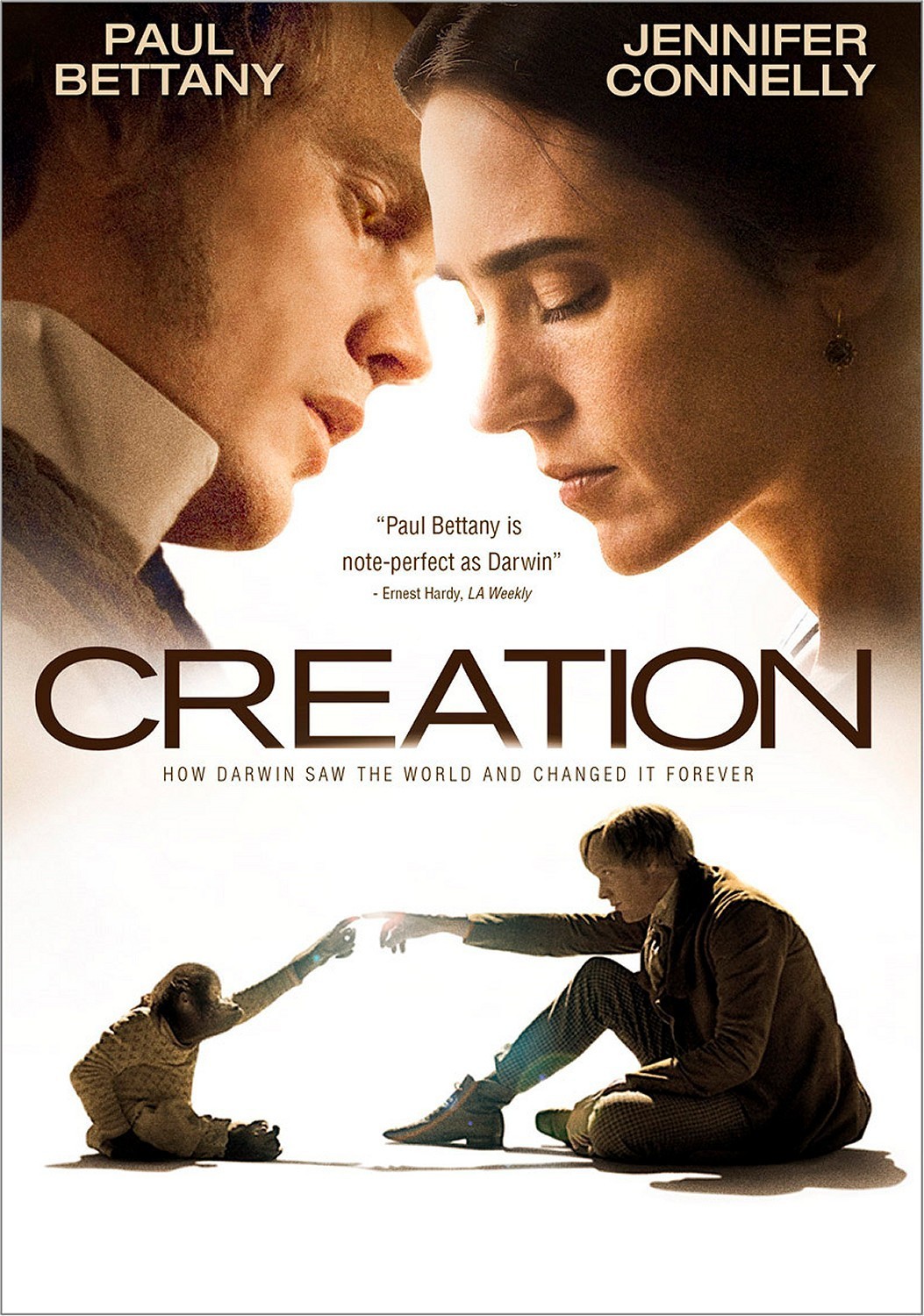

The film stars the real-life couple Paul Bettany and Jennifer Connelly, as Charles and Emma, who a few years before the publication of Origins are grieving the death of their 10-year-old, Annie (Martha West). This loss has destroyed Darwin’s remaining faith in God and reinforced his wife’s. But it is to Charles that Annie reappears through the film, in visions, memories and perhaps hallucinations.

The film suggests that Darwin was forced almost helplessly toward the implications of his theory. He had no particular desire to stir up religious turmoil, particularly with himself as its target. He famously delayed publication of his theories as long as he could. In the film, two close friends tell him he owes it to himself to publish, and Thomas Huxley, who called himself “Darwin’s bulldog,” tells him: “Congratulations, sir! You’ve killed God!”

Not every believer in evolution, including the pope, would agree. But Huxley’s words are precisely those Darwin feared the most. Consider that he had no idea in the 1850s how irrefutably correct his theory was, and how useful it would be in virtually every hard science. Emma and their clergyman, Rev. Innes (Jeremy Northam), try to dissuade him from publishing, but his wife finally tells him to go ahead because he must. If he hadn’t, someone would have: The Theory of Evolution was a fruit hanging ripe from the tree.

Jon Amiel, the film’s director, tells his story with respect and some restraint, showing how sad and weakened Charles is and yet not ratcheting up his grief into unseemly melodrama. One beautiful device Amiel uses is a series of digressions into the natural world, in which we observe everyday applications of the survival of the fittest. What’s often misunderstood is that Darwin was essentially speaking of the survival of the fittest genes, not the individual members of a species. This process took millions of years, and wasn’t a case of humans slugging it out with dinosaurs.

Both Darwins understood and agreed about the role that inheritance (later to be known as genetics) played in health. As first cousins, they wondered if Annie’s life expectancy had been compromised. She died of complications from scarlet fever, which wasn’t their fault — but did they know and believe that?

I have a feeling the loss of their child and the state of their marriage were what most interested the backers of this film. They must have wanted to make a film about Darwin the man, not Darwin the scientist. The filmmakers do their best to keep Darwin’s theory in the picture, but it sadly isn’t fit enough to struggle against the dominant species of Hollywood executives.