It would be hard to describe Griffin Mill’s job in terms that would make sense to anyone who has had to work for a living. He’s a vice president at a movie studio, which pays him enormous sums of money to listen to people describe movies to him. When he hears a pitch he likes, he passes it along. He doesn’t have the authority to give a “go” signal himself, and yet for those who beseech him to approve their screenplays, he has a terrifying negative authority. He can turn them down. Griffin starts getting anonymous postcards from a writer who says he is going to kill him. Griffin’s crime: He said he would call the writer back, and he never did.

Robert Altman‘s “The Player,” which tells Griffin’s story with a cold sardonic glee, is a movie about today’s Hollywood — hilarious and heartless in about equal measure, and often at the same time. It is about an industry that is run like an exclusive rich boy’s school, where all the kids are spoiled and most of them have ended up here because nobody else could stand them. Griffin is capable of humiliating a waiter who brings him the wrong mineral water. He is capable of murder. He is not capable of making a movie, but if a movie is going to be made, it has to get past him first.

This is material Altman knows from the inside and the outside. He owned Hollywood in the 1970s, when his films like “MASH,” “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” and “Nashville” were the most audacious work in town. Hollywood cast him into the outer darkness in the 1980s, when his eclectic vision didn’t fit with movies made by marketing studies. Now he is back in glorious vengeance, with a movie that is not simply about Hollywood, but about the way we live now, in which the top executives of many industries are cut off from the real work of their employees, and exist in a rarefied atmosphere of greedy competition with one another.

“The Player” opens with a very long continuous shot that is quite a technical achievement, yes, but also works in another way, to summarize Hollywood’s state of mind in the early 1990s. Many names and periods are evoked: Silent pictures, foreign films, the great directors of the past. But these names are like the names of saints who no longer seem to have the power to perform miracles. The new gods are like Griffin Mill — sleek, expensively dressed, noncommittal, protecting their backsides. Their careers are a study in crisis control. If they do nothing wrong, they can hardly be fired just because they never do anything right.

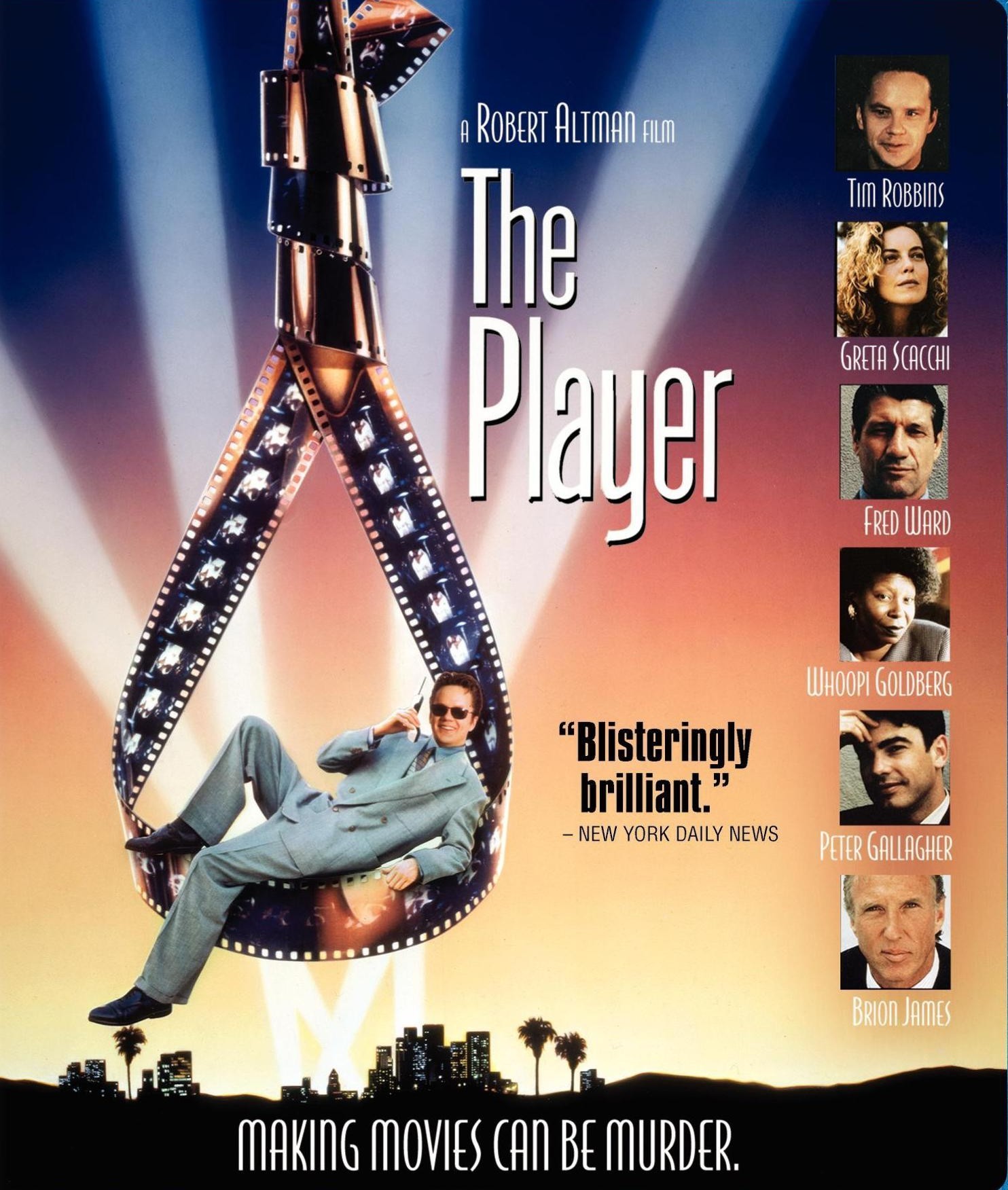

“The Player” follows Griffin (Tim Robbins) during a period when his big paycheck, his luxury car and his expensive lifestyle seem to be in danger. There is another shark in the pond, a younger executive (Peter Gallagher) who may be even sleeker and greedier, and who may get Griffin’s job. This challenge comes at a bad time: Griffin is shedding a girl friend (a woman whose superior intelligence he feeds on, while treating the rest of her like a shabby possession). And there are those postcards. Who is sending the postcards? Griffin racks his memory and his secretary’s appointment book. He has lied to so many writers that there is no way to narrow the field. Finally he picks one name and calls the guy for a meeting. The guy’s girl friend says he’s out in Pasadena, seeing “The Bicycle Thief” at a revival house. Griffin drives out there, meets the guy, has a conversation with him, follows him back to a parking lot, and kills him. As if Griffin didn’t have enough problems already.

The movie then follows Griffin’s attempts to protect his position at the studio, evade arrest for murder, and conduct a romance with the dead man’s fiancé (Greta Scacchi), who if anything is more cynical than Griffin. This story was first told in a novel by Michael Tolkin, who made it so compelling I read it in a single sitting. Now Altman has made it funny as well, without losing any of the lacerating anger and satire.

Altman fills his film with dozens of cameos by recognizable stars, most of them saying exactly what’s on their minds. And he surrounds Griffin with the kind of oddball characters who seem to roll into Los Angeles, as if the continent was on a tilt: Whoopi Goldberg as a Pasadena police detective who finds Griffin hilarious, Fred Ward as a studio security chief who has seen too many old “Dragnet” episodes, Sydney Pollack as a lawyer who does for the law what Griffin does for the cinema, Lyle Lovett as a sinister figure lurking on the fringes of many gatherings.

Watching “The Player,” we want to despise Griffin Mill, but we can’t quite manage that. He is not dumb. He has a certain verbal charm. As played by Tim Robbins, he is tall, with a massive forehead but a Dana Carvey smile, and he wears a suit well. Watching him in some shots, especially when the camera is below eye level and Altman uses a mock-heroic composition, we realize with a shock that Griffin looks uncannily like the young “Citizen Kane“. He has a similar morality, too, but not the breadth of vision.

Altman, who has always had a particular strength with unusual supporting characters, surrounds him with people who all seem to be sketches for movies of their own. The girl friend played by Scacchi, whose name is June Gudmundsdottir, and who may or may not be Icelandic, is an example: A Southern California combination of artistic self-realization (she paints ) and self-interest (for her, romances are like career stages). Peter Gallagher, as the rival young executive, is like the kid at school who could always push your buttons, who was so hateful you could never understand why God didn’t strike him dead for smirking at you all the time. And Whoopi Goldberg, as the cop who is almost certain Griffin is a murderer, brings a certain moral detachment to her job: Would she rather apprehend a perpetrator, or enjoy the human comedy?

“The Player” is a smart movie, and a funny one. It is also absolutely of its time. After the savings and loan scandals, after Michael Milkin, after junk bonds and stolen pension funds, here is a movie that uses Hollywood as a metaphor for the avarice of the 1980s. It is the movie “The Bonfire of the Vanities” wanted to be. There was a full page photo of Robert Altman in one of the newsweeklies, looking sideways at the camera, grinning like someone who has waited a long time, and finally gotten in the last word. As someone who grew up on his great films, it gives me such pleasure to see him make another one. In the same season as “The Babe,” Altman is the guy who has hit one out of the park.