Midway through watching Christopher Bell’s “Bigger, Stronger, Faster,” I started to think about another film I’d seen recently. The Bell documentary is about the use of steroids in sports and bodybuilding. The other film is Darryl Roberts’ “America the Beautiful,” about the guilt some women feel because they don’t look like the models in fashion magazines. The steroid users want to be bigger. The weight-obsessed women want to be thinner.

Bell is one of three brothers. They’ve all used steroids, and two still do. Mike (Mad Dog) Bell had some success in pro wrestling, but never as the star, always as the scripted loser. Wrestling has dropped him, but he’s still in training, even though he’s now “too old,” he’s told. “I was born to attain greatness,” he tells Chris, “and I’m the only one that’s holding myself back.” The Roberts doc focuses on Gerren Taylor, who at 12 achieved fame as a child who looked like an adult fashion model. A year later, she was dropped by those who cast for runway models, but she tried to make a comeback. At 13.

The third Bell brother, Mike (Smelly) Bell, has promised his wife he will stop taking steroids after he achieves his dream of power-lifting 700 pounds. He attains it, but later tells Chris he will use steroids again. Chris tells him, “I’m afraid you’ll lose your job, your wife and yourself.” Smelly replies: “If I lose my job and my wife, what else do I have but myself?” Both of Chris’ brothers are remarkably frank in talking to him, as are his parents, who are “opposed to steroids” but are red-faced while cheering after Smelly lifts the weights.

Bell uses a clip from the movie “Patton,” in which the famous general addresses his troops: “Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser.” That is the bottom line of “Bigger, Stronger, Faster.” We say we’re opposed to steroids, but we’re more opposed to losing. Steroids are not nearly as dangerous as amphetamines, he points out, but the United States is the only nation that requires its fighter pilots to use amphetamines. They may be harmful, but they work.

This movie is remarkable in that it seems to be interested only in facts. I was convinced that Bell was interviewing people who knew a lot about steroids, and the weight of scientific, medical and psychological opinion seems to be: Steroids are not particularly dangerous. Is the movie “pro-steroid”? Yes, but it is even more against the win-win mentality. We demand that our athletes bring home victories, and yet to compete on a level playing field, they feel they have to use the juice.

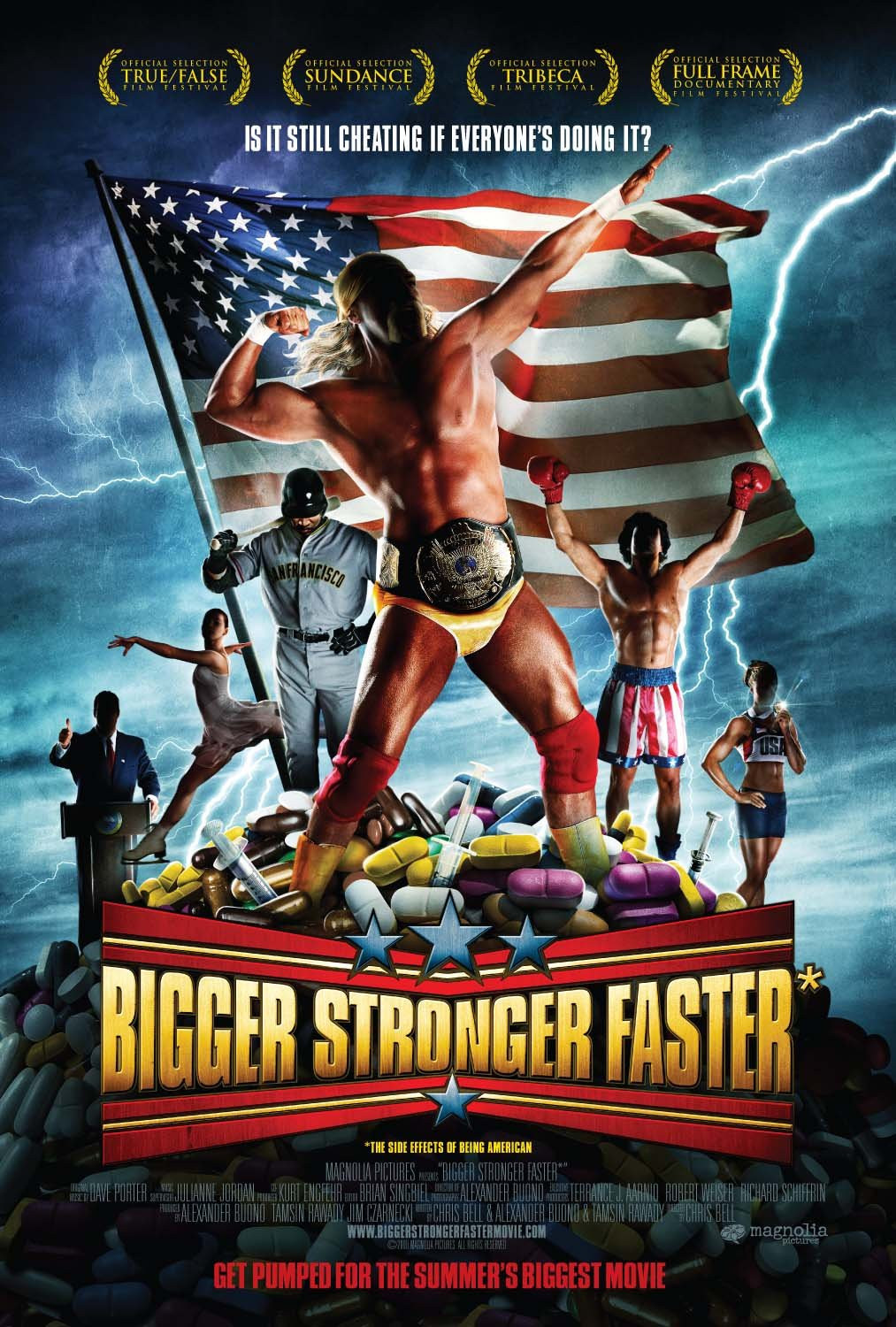

The movie goes against the drumbeat of anti-steroid publicity, news reports and congressional hearings, to say that steroids are not only generally safe, but have been around longer and been used more widely than most people know. Bell and his brothers grew up pudgy in a Poughkeepsie family, were mesmerized by early heroes like Hulk Hogan, Rambo and Conan the Barbarian, got into weight-lifting and still have muscular physiques. They all used muscles as a powerful boost to their self-esteem.

But think for a second. “America the Beautiful” quotes this statistic: “Three minutes of looking at a fashion magazine makes 90 percent of women of all ages feel depressed, guilty and shameful.” I don’t have similar statistics about bodybuilders, but I assume they study the muscle magazines with similar feelings. Those who cannot be too thin or too muscular are attracted to opposite extremes, but use the same reasoning: By pursuing an ideal that is almost unattainable and may be dangerous to their health, they believe they will be admired, successful, the object of envy.

Bell interviews some bodybuilders who are over 50, maybe 60, and still in “training.” The words “in training” suggest that a competition is approaching, but they’re in training against themselves. Against their body’s desire to pump less iron, eat different foods, process fewer proteins and in general, find moderation. Anorexia represents one extreme of this reasoning. At another extreme is Gregg Valentino, who has the world’s largest biceps; they look like 16-inch softballs straining against his skin. He makes fun of himself: He walks into a club and no chick is gonna go for that, “but the dudes come over.” There are men who envy him.

What’s sad is that success in both fashion and bodybuilding is so limiting. For every Arnold Schwarzenegger, who used the Mr. Universe crown to catapult himself into movie and political stardom, there are hundreds, thousands, who spend their lives “in training.” When models get thin enough (few do, especially in their own minds), they must spend their lives staying that thin.

The question vibrating below the surface of both docs is, has America become maddened by the need for victory? When our team is in the World Series, do we seriously give a damn what the home run kings have injected? We are devout in Congress but heathens in the grandstands. That is one of Bell’s messages, and the other is that steroids have become demonized far beyond their actual danger to society. Which side do you vote on? Chris Bell marks his ballot twice: Steroids are not very harmful, but by using them, we reveal a disturbing value system.