The people materialize from out of clear white light, as a bell tolls. Where are they? An ordinary building is surrounded by greenery and an indistinct space. They are greeted by staff members who explain, courteously, that they have died, and are now at a way-station before the next stage of their experience.

They will be here a week. Their assignment is to choose one memory, one only, from their lifetimes: One memory they want to save for eternity.

Then a film will be made to reenact that memory, and they will move along, taking only that memory with them, forgetting everything else. They will spend eternity within their happiest memory.

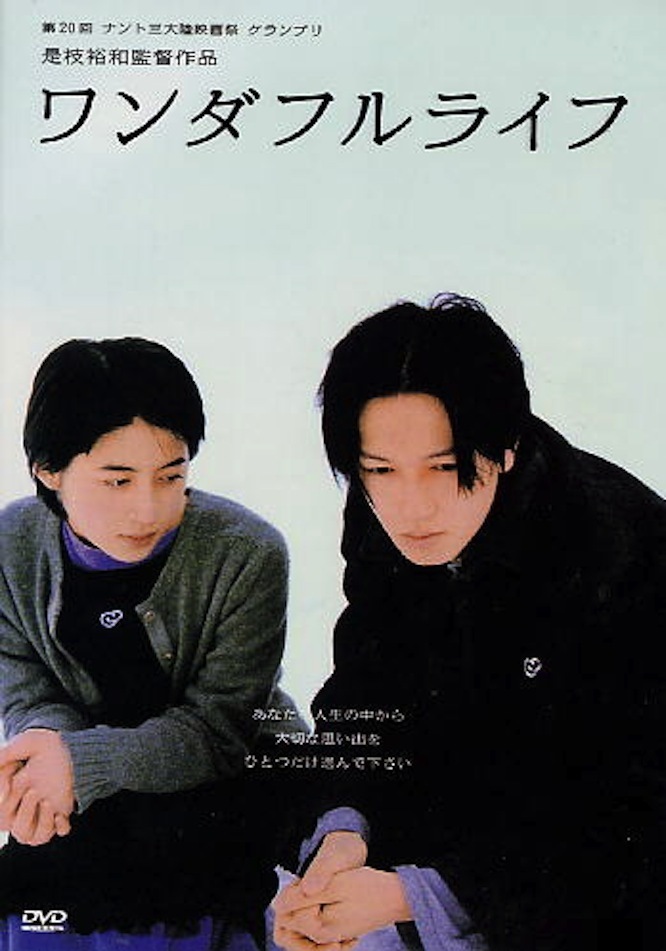

That is the premise of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s “After Life,” a film that reaches out gently to the audience and challenges us: What is the single moment in our own lives we treasure the most? One of the new arrivals says that he has only bad memories. The staff members urge him to think more deeply. Surely spending eternity within a bad memory would be–well, literally, hell. And spending forever within our best memory would be, I suppose, as close as we should dare to come to heaven.

The film is completely matter-of-fact. No special effects, no celestial choirs, no angelic flim-flam. The staff is hard-working; they have a lot of memories to process in a week, and a lot of production work to do on the individual films. There are pragmatic details to be workedout: Scripts have to be written, sets constructed, special effects improvised. This isn’t all metaphysical work; a member of an earlier group, we learn, choose Disney World, singling out the Splash Mountain ride.

Kore-eda, with this film and the 1997 masterpiece “Maborosi,” has earned the right to be considered with Kurosawa, Bergman and other great humanists of the cinema. His films embrace the mystery of life, and encourage us to think about why we are here, and what makes us truly happy.

At a time when so many movies feed on irony and cynicism, here is a man who hopes we will feel better and wiser when we leave his film.

The method of the film contributes to the impact. Some of these people, and some of their memories, are real (we are not told which).

Kore-eda filmed hundreds of interviews with ordinary people in Japan. The faces on the screen are so alive, the characters seem to be recalling events they really lived through, in world of simplicity and wonder.

Although there are a lot of characters in the movie, we have no trouble telling them apart because each is unique and irreplaceable.

The staff members offer a mystery of their own. Who are they, and why were they chosen to work here at the way-station, instead of moving onto the next stage like everybody else? The solution to that question is contained in revelations I will not discuss, because they emerge sonaturally from the film.

One of the most emotional moments in “After Life” is when a young staff member discovers a connection between himself and an elderly newarrival. The new arrival is able to tell him something that changes hisentire perception of his life. This revelation, of a young love long ago, has the kind of deep bittersweet resonance as the ending of “The Dead,” the James Joyce short story (and John Huston film) about a man who feels a sudden burst of identification with his wife’s first lover, a young man now long dead.

“After Life” considers the kind of delicate material that could bedestroyed by schmaltz. It’s the kind of film that Hollywood likes to remake with vulgar, paint-by-the-numbers sentimentality. It is like a transcendent version of “Ghost,” evoking the same emotions, but deserving them. Knowing that his premise is supernatural and fantastical, Kore-eda makes everything else in the film quietly pragmatic. The staff labors against deadlines. The arrivals set to work on their memories. There will be a screening of the films on Saturday–and then Sunday, and everything else, will cease to exist. Except for the memories.

Which memory would I choose? I sit looking out the window, as images play through my mind. There are so many moments to choose from. Just thinking about them makes me feel fortunate. I remember a line from Ingmar Bergman’s film “Cries and Whispers.” After the older sister dies painfully of cancer, her diary is discovered. In it she remembers a day during her illness when she was feeling better. Her two sisters and her nurse join her in the garden, in the sunlight, and for a moment pain is forgotten, and they are simply happy to be together. This woman who we have seen die a terrible death has written: “I feel a great gratitude to my life, which gives me so much.”