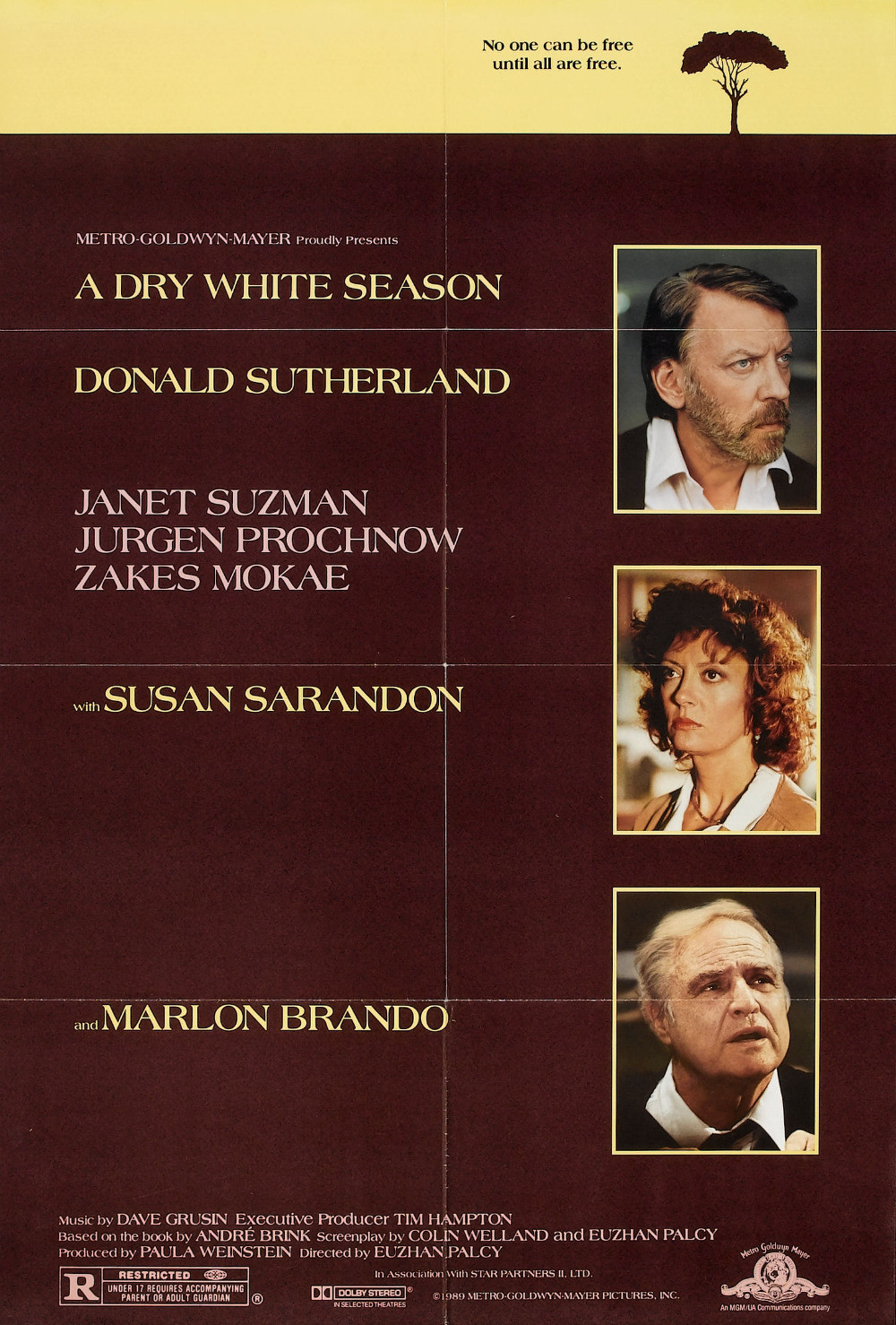

When you are safe and well-off, and life has fallen into a soothing routine, there is a tendency to look the other way when trouble happens – especially if it hasn’t happened to you. Say, for example, that you are a white schoolmaster in South Africa and live in a comfortable suburban home with your wife and two children. Suppose your African gardener’s son disappears one day. How do you feel? You feel sorry, of course, because you have humanitarian instincts. But if it appears that the boy was the victim of police brutality, and may be imprisoned illegally? What do you do then? In a country where the gardener has little hope of lodging an effective appeal, do you stick your neck out and help him? That is the question posed to Ben du Toit (Donald Sutherland) in the opening passages of “A Dry White Season.” His answer is almost instinctive: “Best to let it go,” he tells the gardener. “No doubt they’ll see they made a mistake and release him. There’s nothing to be done.” This is a sensible answer, if the boy is not your son. But Gordon Ngubene (Winston Ntshona), the gardener, cannot accept it. With the help of an African lawyer, he tries to get some answers, to find out why and how his son disappeared. And it is not very long until Gordon has disappeared, too.

“A Dry White Season” is set in the 1970s, at the time when the schoolchildren of Soweto, an African township outside Johannesburg, held a series of protests. They wanted to be educated in English, not Afrikaans (a language spoken only in South Africa and mostly by whites). The protests resulted in the deaths of many marchers, but the government weathered the storm and clapped a lid on the possibility of a civil uprising, as it always has.

Now we have arrived at another season of protest in South Africa, where to the general amazement of almost everyone involved, peaceful anti-government marches were permitted by the government in Cape Town and Johannesburg. As someone who has visited South Africa and studied for a year at the University of Cape Town, I wonder what the average American reader makes of the headlines. How does he picture South Africa? What does he think life is like there? Does he see these marches in the same context as American freedom marches? Does he ask how 6 million whites can get away with ruling 24 million Africans? This film, based on a novel by Andre Brink, provides a series of bold images to go with the words and the concepts in the stories out of South Africa. Like “A World Apart” (1988), it is set mostly in the pleasant world of white suburbia, an easy commute from the skyscrapers of downtown (some Americans, I believe, still see South Africa in images from old Tarzan movies, and do not know the country is as modern and developed as anyplace in Europe or North America). We meet the schoolteacher, a decent and quiet man, a onetime Springbok sports hero, who finds it easy not to reflect overlong on the injustices of his society. He disapproves of injustice in principle, of course, but finds it prudent not to rock the boat.

Then disaster strikes into the life of the gardener, who also loves his family, and who also lives a settled family life, in a township outside the city. Jonathan, the gardener’s son, is a clever lad, and the schoolteacher is helping him with a scholarship. Jonathan is arrested almost at random, and jailed with many other demonstrators, and then a chain of events is set into motion that leads Ben du Toit into a fundamental difference with the entire structure of his society.

The movie follows him step by step, as he sees things he can hardly believe, and begins to suspect the unthinkable – that the boy and his father have been ground up inside the justice system and spit out as “suicides.” He meets with the African lawyer (Zakes Mokae) and with the gardener’s wife (Thoko Ntshinga). He finds one Catch-22 being piled on another. (After her husband is reported dead, the widow no longer has a legal right to stay in her house and must be deported to a “homeland” she has never seen, from where it will be impossible to lodge a legal protest.) As a respected white man, he is allowed access to the system – until it becomes obvious that he is asking the wrong questions and adopting the wrong attitude. Then he is ostracized. He loses his job.

Shots are fired through his windows. His wife (Janet Suzman, brittle and unforgiving) is furious that he has betrayed his family by appearing to be a “kaffir lover.” His daughter finds him a disgrace.

Only his young son seems to understand that he is wearily, doggedly, trying to do what is right.

“A Dry White Season” is a powerfully serious movie, but the director, Euzhan Palcy, provides a break in the middle, almost as Shakespeare used to bring on pantomime before returning to the deaths of kings. A famous South African lawyer, played by Marlon Brando, is brought in to lodge an appeal against the finding that one of the dead committed suicide. The Brando character knows the appeal is useless, that his courtroom appearance will be a charade, and yet he goes ahead with it anyway – using irony and sarcasm to make his points, even though the outcome is hopeless.

Brando, in his first movie appearance since 1980, has fun with the role in the way that Charles Laughton or Orson Welles would have approached it. He allows himself theatrical gestures, droll asides, astonished double takes. His scenes are not a star turn, but an effective performance in which we see a lawyer with a brilliant mind, who uses it cynically and comically because that is his form of protest.

At the center of the film, Donald Sutherland is perfectly cast and quietly effective as a man who will not be turned aside, who does not wish misfortune upon himself or his family, but cannot ignore what has happened to the family of his friend. Like “A World Apart” and “Cry Freedom,” the movie concentrates on a central character who is white (because the movie could not have been financed with a black hero), but “A Dry White Season” has much more of the South African black experience in it than the other two films.

It shows daily life in the townships, which are not slums but simply very poor places where determined people struggle to live decently. It hears the subtleties of voice when an intelligent African demeans himself before a white policeman, appearing humble to gain a hearing. It shows some of the details of police torture that were described in Joseph Lelyveld’s Move Your Shadow, the most comprehensive recent book about South Africa. It provides mental images to go with the columns of text in the newspapers. American network TV coverage of South Africa all but ended when the government banned the cameras (proving that the South African government was absolutely right that the networks were interested only in sensational footage, and not in the story itself). Here are some pictures to go with the words.

Here is also an effective, emotional, angry, subtle movie.

Palcy, a gifted filmmaker, is a 32-year-old from Martinique, whose first feature was the masterpiece about poor black Caribbean farm workers, “Sugar Cane Alley.” Here, with a larger budget and stars in the cast, she still has the same eye for character detail. This movie isn’t just a plot, trotted out to manipulate us, but the painful examination of one man’s change of conscience. For years he has been blind, perhaps willingly. But once he sees, he cannot deny what he feels is right.