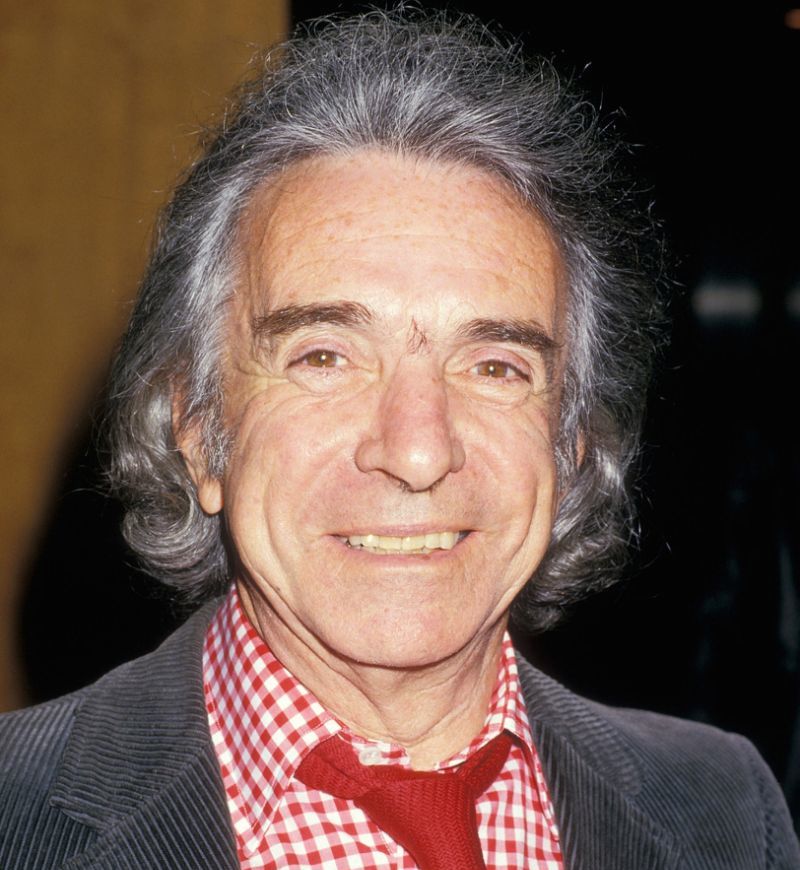

When people talk about film directors and their work, they generally wind up discussing the technical and stylists flourishes that make their work so distinctive—the rhetorical flourishes of Quentin Tarantino, the stunning visual touches of Martin Scorsese, the way that Alfred Hitchcock effortlessly manipulates viewers in order to achieve maximum suspense. On the other hand, there are some filmmakers who don’t fit so easily into that particular mode. Take the films of Arthur Hiller, for example. On the one hand, even the most ardent auteurist might come up short if you were to ask them to suggest the ultimate Hiller shot because that is simply not the kind of director he was—he was more concerned with serving the material than in showing off his technical expertise. This might make him sound a little boring on paper but it resulted in a career that began in the early days of television and stretched out over 33 films that included a number of big hits, one all-time classic and what I consider to be one of the funniest movies ever made. That career ended today with his passing at the age of 92. As a brief glimpse of that filmography reveals, he showed himself to be a director of impeccable integrity as well as one who was willing to experiment with a wide variety of genres over the years.

Hiller was born on November 22, 1923 in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, where his Jewish family emigrated from Poland a decade earlier. Although not theatrical people by any means, Hiller’s parents would help put on a couple of plays a year for the local Jewish community and he began to help out with them at a young age, which, he once stated in an interview, helped fuel the interest that would lead to his eventual career. After graduating from high school, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and fought in World War II in the skies over Europe. After returning home, he attended college in Toronto and after receiving a Master of Arts in psychology in 1950, he went to work for Canadian radio. When television arrived for good in the early 1950s, he began directing shows for local broadcasters. His work caught the notice of NBC and he came to the United States, working in the next decade in the emerging medium, directing episodes of (among many, many shows) “Playhouse 90,” “Wagon Train,” “Gunsmoke,” “Perry Mason” and “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.”

He made his feature film directorial debut in 1957 with “The Careless Years,” a low-budget teensploitation film about two high school kids (played by Dean Stockwell and Natalie Trundy) from different social situations—she’s rich and he’s poor—whose blossoming romance is met with distaste from both of their families. After a few more years in television, he returned to features with “Miracle of the White Stallions” (1963), a cute live-action Disney film about the efforts to save a bunch of Lipizzaner stallions located in Vienna during World War II. Later that year (the two-movies-in-one-year trick would be one that he would pull off several times throughout his career), he switched gears with “The Wheeler-Dealers,” a cheerfully frothy romantic comedy featuring James Garner as a Texas oil tycoon who acts dumber than he actually is (he is even an Ivy League graduate) and Lee Remick as the stockbroker he gets involved with while in New York City on business. This is not a film that was ever destined to go down in the history books but Hiller put it together in a smooth manner and managed to get some breezily charming performances from his two leads. The end result is no classic but if you happen to stumble upon it on TCM some day, watching it is a more than painless way to spend a couple of hours.

His next film was both another significant change of pace from his earlier work and a straight-up classic to boot. This was “The Americanization of Emily” (1964, pictured above), one of the darkest, boldest and funniest anti-war satires that Hollywood ever created. Written by Paddy Chayefsky (the first of two collaborations with Hiller), the story (adapted from William Bradford Hue’s novel) takes place in London in 1944 during the weeks leading up to the D-Day invasion and focuses on Lt. Commander Charlie Madison (Garner), a “practicing coward” whose main military duty is to supply his superiors with booze and women. Through circumstances too complex to go into here, he ends up with a group of combat engineers who will be among the first to storm Omaha beach and winds up becoming the first casualty of the invasion. Although this devastates his new love (Julie Andrews), who already lost a husband to the war and fell for Charlie in part because she assumed he would never actually see combat, Charlie becomes a hero around the world because of his sacrifice but … well, you will just have to find out what happens next. I generally shy away from describing films as being “perfect” but this one is close enough to deserve the appellation because everything about it works. The screenplay by Chayefsky is both brutally hilarious and surprisingly humane and is one of the few times when he actually wrote dialogue that sounded like people speaking to each other instead of speechifying. The performances across the board were great as well—Garner and Andrews turned in some of the finest work of their respective careers here. As for Hiller, he took incredibly tricky material and found just the right tone for it. While the end result was not a success at the box office (for many years, it was fairly difficult to even see), it has in recent years received the critical reappraisal that it deserves.

Perhaps as the result of the failure of “The Americanization of Emily,” Hiller spent the next few years directing a series of more seemingly commercial product. There was “Promise Her Anything” (1965), a British-based romantic comedy co-starring Warren Beatty and Leslie Caron, “Penelope” (1966), a comedy about a frustrated upper-crust housewife (Natalie Wood) who steals from friends and even robs the bank managed by her inattentive husband. “Tobruk” (1967) was a WWII film with Rock Hudson leading a attack designed to blow up German fuel reserves and halt the approach of Rommel’s tank corps. “The Tiger Makes Out” (1967) is a weird comedy about a frustrated mailman (Eli Wallach) who decides to kidnap a beautiful young woman, imprison her in his basement and make her love him—alas, he unfortunately kidnaps a middle-aged housewife (Anne Jackson) and wackiness ensues. “Popi” (1969) was a sentimental comedy-drama featuring Alan Arkin as a Puerto Rican widower struggling to raise his two sons in New York’s Spanish Harlem. Based on a Neil Simon screenplay, “The Out of Towners” (1970) depicted the comedic horrors that ensue when a staid Ohio couple (Jack Lemmon and Sandy Dennis) visit the Big Apple. Truth be told, none of these movies are particularly good but their failings are almost entirely due to the material—to whatever degree they are watchable today, it is almost entirely due to Hiller’s clean and efficient direction.

Later in 1970, he would have what would become far and away his biggest hit—one of the biggest hits in Hollywood history to that point—in a seemingly simple (some might argue simple-minded) that utilized the basic premise of his debut feature (a rich Harvard jock falls in love with a poor-but-beautiful Radcliffe student, much to the disapproval of his parents who threaten to cut him off financially unless he dumps her), added a melodramatic twist (if you have read this far, there is no way that you do not know that she is suffering from The Terminal Disease That Has No Name) and coated it all with a score by Francis Lai that you either found catchy or cloying. The title? “Love Story” (pictured above). To be polite, this particular film has never been my cup of tea. The screenplay by Erich Segal is ghastly and even though a couple of lines from it would eventually enter the vernacular, especially the immortal “Love means never having to say you’re sorry,” I don’t know anyone who quotes them today who isn’t making some kind of joke. My guess is that Hiller must have realized that the material was kind of awful but nevertheless handled it in a serious and straightforward manner instead of playing up the soap-opera stuff. Together with the undeniably chemistry struck by co-stars Ryan O’Neal and Ali McGraw, the film struck a chord with audiences and became an enormous hit and received seven Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director for Hiller. (He lost but would win the Golden Globe for his direction).

Having supercharged his career with the success of “Love Story,” Hiller once again found himself experimenting with a number of different genres with varying degrees of success. “Plaza Suite” (1971) was an adaptation of the Neil Simon stage comedy that was already a bit stodgy and dated even though it was only three years old. He reunited with Chayefsky on “The Hospital” (1971), an angry and oftentimes hilarious black comedy starring George C. Scott (in one of his finest performances) as the beleaguered Chief of Medicine at a decrepit teaching hospital dealing with depression over his personal and professional failings, the usual day-to-day catastrophes at work and the mysterious deaths of members of his staff. He stepped in to direct the screen version of “Man of La Mancha” (1972) during its chaotic pre-production period but demonstrated no real flair for the musical genre. Plus, bizarre casting of non-singers Peter O’Toole (who was already signed on before Hiller) and Sophia Loren pretty much doomed it from the start—it doesn’t even work as camp today. “The Crazy World of Julius Vrooder” (1974) was a largely forgotten quirkfest about a Vietnam vet (Timothy Bottoms) who escapes from the VA hospital and builds his own hangout underneath a highway, even acquiring free electricity and phone service. “The Man in the Glass Booth” was an interesting adaptation of the book and play by Robert Shaw about the trial of a Jewish holocaust survivor (Maximilian Schell) who is accused of actually being a Nazi war criminal and taken to Israel for trial.

He began 1976 with “W.C. Fields and Me,” a biopic of the legendary comedian based on a memoir by his mistress that did no favors to anyone—not to Hiller (who decided to emphasize a sentimental approach to dealing with that most cynical of comics), not to co-stars Rod Steiger and Valerie Perrine and certainly not to the legacy of Fields. Although a complete disaster, Hiller’s career was not effected by it thanks to quickly following it up a few months later with the smash hit suspense comedy “Silver Streak,” which told a Hitchcock-inspired tale of murder and intrigue set aboard a train heading to Chicago and featuring Gene Wilder as the proverbial Man Who Knows Too Much and Richard Pryor as the petty criminal who helps him out. Truth be told, the film is not quite as funny as you may remember it being but Hiller’s decision to put Wilder and Pryor together proved to be a combustible combination that helped save the movie. (In one especially famous instance, he let them play around with a scene that involved Wilder doing himself up in blackface to escape detection—a conceit that was deeply questionable even then—and transformed it into a bit that was kind of racist into one that commented on the inherent racism in a bracingly funny manner.) In 1979, Hiller had two entries in that summer’s movie derby—while “Nightwing,” a “Jaws” knockoff featuring killer bats that would prove to be Hiller’s only horror film, “The In-Laws” (pictured above) would prove to be a genuine comedy classic. Having just written at extensive length on that particular film for this site just a few weeks ago, I don’t really have much more to say about it except to note that if I were to make one of those seven best lists that are currently clogging the Internet dealing with the greatest screen comedies of all time, it would definitely have a place of honor on it.

“The In-Laws” would prove to be Hiller’s last truly great film. At this point, the film industry was shifting inexorably into the flashy blockbuster mode and while Hiller worked steadily, the material was not always up to his usual standards. “Making Love” (1982) was an early attempt by Hollywood to deal with homosexuality in a straightforward matter that sadly devolved into a turgid soap opera. “Author! Author!” (1982) was an odd comedy about a playwright trying to raise a brood of adorable kids while putting on a new show that was undermined by the weird decision to cast Al Pacino in the lead. “Romantic Comedy” (1983) was an adaptation of the Bernard Slade play that proved to be as memorable as its title. “The Lonely Guy” (1984) was a pretty good Steve Martin comedy about a greeting card writer who parlays his bad luck with women into a best-selling guide to fellow lonely guys. “Teachers” (1984) tried to do for inner-city schools what “The Hospital” did for inner-city hospitals and didn’t. His biggest hit of the period was “Outrageous Fortune” (1987), a female buddy comedy with Bette Midler and Shelly Long teaming up to track down the boyfriend that they unknowingly shared and who appears to have faked his death. “See No Evil, Hear No Evil” (1989) saw Hiller reuniting with Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor for a convoluted caper film in which one of them is blind and the other one is deaf—if it is remembered today at all, it is for containing one of the first major screen performances by the then-unknown Kevin Spacey.

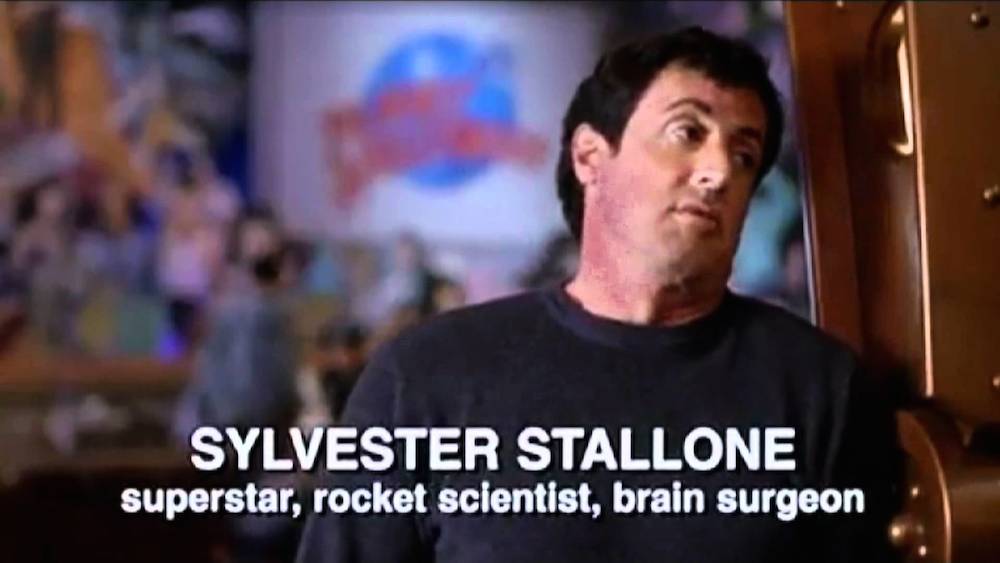

Perhaps realizing that he wasn’t getting the kind of material suitable to his talents, Hiller began to pull away from filmmaking, though he continued to be a key player in the industry. He served as the president of the Directors Guild of America from 1989 to 1993. Following that term of service, he went on to become the president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1993 to 1997—the group would eventually reciprocate by presenting him with the esteemed Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2002 for his contributions to the industry. During this time, he still remained active behind the camera. “Taking Care of Business” (1990) was a wacky comedy in which Jim Belushi breaks out of prison in order to see the Cubs in the World Series and winds up taking over the life of a harried ad executive (Charles Grodin) after finding the guy’s then-valuable day planner. (Oddly, it was co-written by the then-unknown J.J. Abrams). “Married to It” (1991) was a comedy/drama about three New York couples reassessing their marriages in a film that was pleasant enough but which almost seemed to be from a different era. “The Babe” (1992) was a biopic of Babe Ruth (John Goodman) that emphasized the darker side of his character—an interesting choice but one that found little favor with audiences. “Carpool” (1996) was made during that odd blip in time when a vehicle toplining Tom Arnold could exist. The weirdest film of this period—hell, of his entire career—was “An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn” (1998, pictured above), a Hollywood satire based around the then-current DGA rule that a director wanting to take his name off of a movie had to use the non de plume “Alan Smithee”—the joke here is that the director (Eric Idle) of a $200 million film wants to take his name off when it is taken away by the studio but oops, his name really is Alan Smithee! To add to the irony (unless it was all a big meta-joke), Hiller had the film taken away from him by writer-producer Joe Eszterhas and wound up employing the sobriquet himself. Perhaps it is no wonder that it took eight years to return behind the camera for what would prove to be his final film, “National Lampoon’s Pucked” (2006), featuring Jon Bon Jovi as a guy trying to form an all-female hockey team.

Even though I have spent the last couple of paragraphs writing about his lesser films, that is not in any way meant to suggest that I am down on Arthur Hiller and his career. With the exception of “Burn Hollywood Burn,” even those lesser films were the work of a consummate professional—even if they didn’t work, he never embarrassed himself in any way. Furthermore, if you look back on his entire filmography, you see a man who managed to come up with at least three bona fide classics in “The Americanization of Emily,” “Love Story” and “The In-Laws” and a number of other perfectly solid efforts, showed a flair for talent that knew how to bring the right actors together while demonstrating an eye for new performers and who earned and maintained the respect and admiration of the industry for several decades. In my book, at least, that makes for both a life and a career well-served.

Oh, and yeah—“SERPENTINE!”