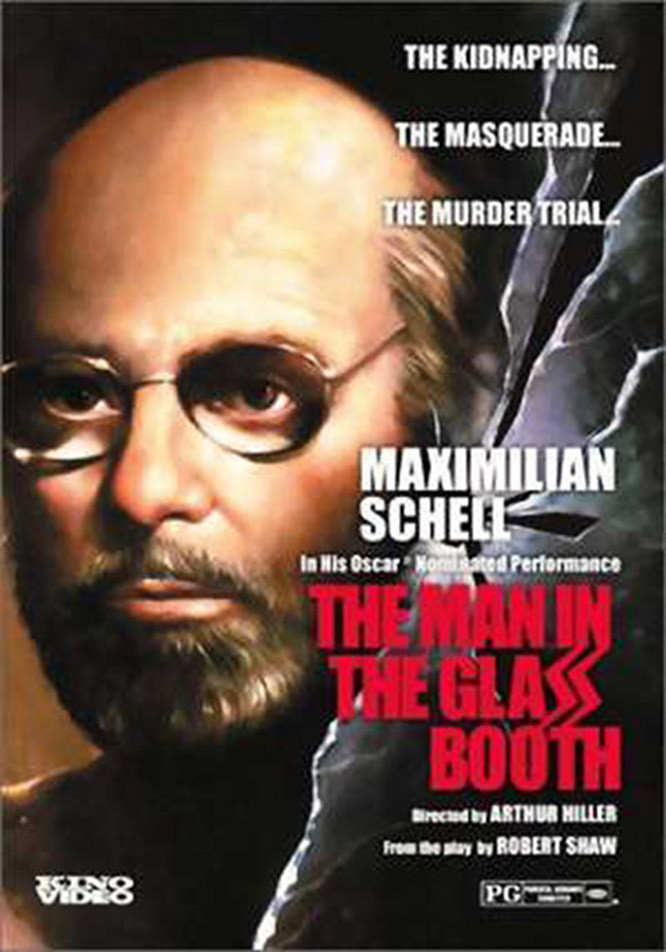

He inhabits a penthouse far above New York City. It’s filled with an accumulation of expensive possessions – with antique furniture, rich draperies, paintings, souvenirs of what seems to have been a successful career as a land developer. He tyrannizes his faithful male secretary with barked commands, with sudden shifts of mood, with bursts of paranoia. He likes to perch on his parapet and survey the city through a telescope. He is not searching idly: He believes he is being followed by men in a blue Mercedes. He is quite clearly mad. His history is a painful one. His name is Arthur Goldman, and he was an inmate of a Nazi concentration camp. To this day his nightmares are punctuated with the fearsome presence of Dorf, commandant of the camp. Thirty years have passed, and yet Dorf controls him still. Or does he control – did he create – Dorf himself? That is the last and most puzzling question raised by “The Man in the Glass Booth,” which is the inaugural offering of the American Film Theater’s second season. It turns out that Goldman is correct after all; there ARE men following him in a blue Mercedes. They’re Israeli agents, and they arrest him and return him to Israel to stand trial. Because he isn’t Goldman at all, they charge; he is himself the war criminal Dorf. There is some evidence for this view. In his apartment is a secret room, filled with Nazi memorabilia, and on the night before his arrest he goes there to attempt to burn the SS number and blood type from his arm. In Israel, he announces that he will conduct his own defense. It’s not much of a defense. He gladly admits his crimes, describes them in great detail and argues only that he was following orders. A bullet-proof glass booth is constructed to shield him from possible assassins, and the trial begins. It proceeds more or less according to schedule, until an astonishing charge is made: Dorf was not posing as Goldman – Goldman was posing as Dorf!

Goldman, or the latest in a series of Goldmans. Because “Arthur Goldman” itself was a name bought and sold in the concentration camp by inmates condemned to die under their own names. It was an identity passed along until no one was really Arthur Goldman. And so the enigma grows more labyrinthine: Did “Goldman” take the identity of Dorf in a classic case of the persecuted identifying with his persecutor? Or did Dorf take Goldman’s identity to shield himself from punishment for his crimes? Who IS the man in the glass booth?

It’s impossible to say for sure, but the point of “The Man in the Glass Booth” isn’t really to answer that question. It’s to pose disturbing notions about the nature of human identity, guilt and responsibility. And it’s to illustrate the ways in which the holocaust was a wrong of such monstrous evil that individual personalities were obliterated by it. Films like “Judgment at Nuremberg” began with the assumption that morality could be upheld and responsibility assigned. “The Man in the Glass Booth” is an infinitely more despairing work. Arthur Hiller’s film for the AFT is a very good one, although it suffers from one basic problem. By its very nature, film tends to be a realistic medium, photographing the outsides of real world. Robert Shaw’s play, even as adapted and made somewhat more realistic by Edward Anhalt, is nevertheless a symbolic and mannered one. Situations and dialog which work within a stylized stage setting sometimes seem incongruous, affected, in this objective film world. The man in the booth, whoever he is, is played by Maximillian Schell, who has become something of a specialist at roles like this (his credits include “Judgment at Nuremberg,” “The Pedestrian” and “The Odessa File.”) He creates a personality here that fits his character’s tortured dialog and projects a special madness in scenes where his logic leads in inhuman conclusions. Lois Nettleton was a fine choice as the Israeli prosecutor. She has a steadiness and intelligence and doesn’t back down. She’s the closest thing the film has to a moral center.

And Hiller’s direction is effective at gradually uncovering the hell of Goldman-Dorf’s torturous past. At first we’re uncertain how to take this strange character, striding about his penthouse and changing the subject – obsessively and urgently – every 30 seconds. But without ever seeming to explain, Hiller quietly leads us into his world, and into a story which can finally end only when Goldman kills Dorf, or Dorf kills Goldman, or they die together.