● “Ironclad” (2011)

● “Black Death” (2010)

“Ironclad ” is now available on DirecTV and other on-demand providers (check your service listings) and from Netflix (DVD and Blu-ray) starting on July 26th. “Black Death” is available on Netflix (streaming, DVD and Blu-ray) and Amazon Instant Video.

When I was a kid growing up in the Seattle suburb of Edmonds, WA (aka “The Gem of Puget Sound”), my parents did everything that good, sensible parents should do to shield their kids from violence, both real and reel. I remember being innocently intrigued by the furor over “Bonnie and Clyde” in 1967, but they would never have taken me to see it with them (to their credit, since I was only six). The same held true for “The Wild Bunch” in 1969, by which time the debate over movie violence had reached a fever pitch in our national conversation. Over the ensuing decades, that conversation has become a moot point as movie violence proceeded apace, from Sonny Corleone’s death in a hail of Tommy-gun fire in “The Godfather” (1972), to the slasher cycle of the late ’70s and ’80s (when makeup artists Tom Savini and Rick Baker reigned supreme as a master of gory effects) and into the present, when virtually anything – from total evisceration to realistic decapitation — is possible through the use of CGI and state-of-the-art makeup effects. That’s where movies like “Ironclad” and “Black Death” come in, but more on those later.

If you’re looking for a rant against milestone achievements in the depiction of graphic violence, you’ve come to the wrong place. To me, it’s a natural progression. Movies and violence have always been inextricably linked, and once opened, that Pandora’s Box could never be closed. A more relevant discussion now is how the new, seemingly unlimited gore FX should be used and justified. Horror films will always be the testing ground for the art of gore, and it would be a crime against cinema to cut the “chest-burster” from “Alien” (or, for that matter, Samuel L. Jackson‘s spectacular death in “Deep Blue Sea“). But it’s the depiction of authentic, real-life violence — in everything from the “CSI” TV franchise to prestige projects like HBO’s “Band of Brothers” and “The Pacific” — that pushes previously unrated levels of gore into the mainstream.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not praising this progression so much as acknowledging its inevitability. If you really love movies — and especially if you’ve been lucky enough to make a career out of watching them — you have undoubtedly seen a violent film that was unquestionably vile, unjustified and miles beyond the boundaries of all human decency. I’ve seen violent movies that earned my disgust because (1) the context of the violence was as abhorrent as the violence itself and (2) the intentions of the filmmakers were clearly indefensible. (Context and intention: More on that later.) Tolerances and sensibilities may vary, but every critic has seen a film that appeared to have been written and directed by sociopaths. Check out Roger Ebert’s review of “I Spit on Your Grave” (the 1978 version) and you’ll see what I mean.

The subject of war is another matter altogether. Vietnam ended decades of sanitized combat in the American movie mainstream, and Oliver Stone‘s “Platoon” showed us wartime atrocity as it really is: brutal, inhuman and perpetrated in the context of battle-weary extremes. “Saving Private Ryan” legitimized the kind of gore previously restricted to graphic horror films because Steven Spielberg knew it would be dishonest to hold back. We had matured enough, as a society, to accept graphic wartime carnage from an A-list director in an Oscar-worthy film because (1) that level of gory realism was now technologically possible and (2) by 1998, enough precedents had been set to mandate that any realistic depiction of warfare must not flinch from the genuine horrors of war: severed limbs, arterial blood-spray, bullets through heads and bodies blown to pieces. This wasn’t the gratuitous gore of exploitative horror, bloody Westerns and street-gang melodrama; the film’s violence was immune to protest because it honored the experience of our soldiers. This is what they went through; this is what they saw. This is what all soldiers go through; this is what all warriors will see.

Of course, the new FX technologies can be abused and trivialized as much as the old ones were; the “Saw” and “Final Destination” franchises (to name but two) are nothing if not showcases for cleverly contrived ways to maim, disfigure and kill, giving FX artists ample opportunity to hone and perfect their craft. But if the goal is to honestly and justifiably depict the terrible things that can happen to human flesh and blood, you have to hand it to effects artists like the KNB EFX Group (founded by industry veterans Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger), who can design and execute virtually any kind of movie violence and make it look horrendously real.

Even before the rise of makeup wizards like Savini, Baker, Rob Bottin, Greg Cannom and the guys at KNB, I realized, early on, that there are as many ways of responding to movie violence as there are ways of depicting it. A severed head can be freakishly satisfying (James Earl Jones’s fate in “Conan the Barbarian”), nightmarishly shocking (as when Brando drops Frederick Forrest’s severed head into Martin Sheen‘s lap in “Apocalypse Now“) or outrageously funny (Stuart Gordon‘s “Re-Animator“). Cartoonish, over-the-top violence (as in, say, Peter Jackson‘s “Dead Alive” or Edgar Wright‘s “Shaun of the Dead“) can be both gruesomely extreme and comically cathartic. It’s all about context and intention.

By the time I was ten, my parental restrictions eased up a bit: I’d developed a voracious appetite for relatively tame horror and science fiction movies on TV, and I was allowed to see PG-rated horror and sci-fi at the Lynn Twin, a two-screen cinema in Lynnwood (the neighboring suburb, due east from Edmonds, where I currently reside). Movies like “Taste the Blood of Dracula” (1970), “Tales from the Crypt” (1972) and “Westworld” (1973) delivered relatively “discreet” violence, mostly in the form of bright red, stylized bloodshed and not-always-convincing severed limbs made from crude rubber moldings. This was cool stuff for movie-loving kids like me. I didn’t have an unusual “sick kid” appetite for it, but I never shied away from it, either. That’s still true today: I don’t seek out movie violence, and much of it (as always) remains abhorrent, exploitative and genuinely disturbing both in context and intention. But if violence is an integral part of the story you’re telling (by which I mean, if it serves the integrity of your story), then it seems to me that depicting it honestly and graphically is not only justified but necessary.

To those who abhor all movie violence and yearn for the good ol’ days of bloodless bullet-holes and carnage-free battlefields, the same options still apply: Don’t buy a ticket to that violent movie, don’t watch that violent TV show, and familiarize yourself with the parental controls on your TV and computer that prevent your kids from seeing that stuff. Just don’t fool yourselves: If your kid is curiously inclined to taste forbidden fruit, they will find a way to pick it.

Like many kids, I knew when a movie death had been sanitized. I grew up with those bloodless bullet-hits and too-clean battlefields, when filmmakers faced a strict, cultural mandate to avoid any graphic depiction of realistic violence. Kids today don’t have that historical perspective; assuming they have access to it, they can see and (this is where it gets troublesome) interactively participate in pretty much any kind of graphic violence, so while the Department of Defense recruits warriors of the future based on proven skill in violent-battle video games, we still need to ask ourselves what a steady diet of violent imagery can do to a young person’s mind. Violent death and dismemberment is virtually ubiquitous, especially in video games. Gratuitous violence is more prominent than ever; body counts have risen exponentially, and desensitizing kids to violence is still a symptom worthy of serious concern. Parents need to be more vigilant than ever in controlling what their kids are exposed to. That’s as it should be.

But here’s the deal: As a kid watching all those bloodless bullet-hits and fully-intact corpses on miraculously crimson-free battlefields, I felt vaguely patronized, condescended to and cheated. That’s not death, I thought, and that’s not war. I’d seen actual battle-carnage photos. I knew that movies were sanitized and I understood why, but I still felt like “the grown-ups” were not being honest. If you’re going to show people killing and dying, then why not show it for real? Sanitizing it was a cheat — not just a cultural expression of institutionally-imposed discretion and decorum by way of the MPAA ratings system (an arbitrary and inconsistent system of moral watchdogging if ever there was one), but a deliberate denial of the truth: Violent death is just that: violent, gruesome, and horrible. The only thing worse than showing it, I thought, was cleaning it up and denying its reality. Gratuitous violence will always be with us; it’s got a track record of easy profit. But if you’re going to make a film about warriors at war, regardless of the era or extremity of battle, then isn’t it dishonest to shy away from graphic authenticity?

All of which brings us to movies like “Ironclad,” “Black Death” and, by extension, HBO’s “True Blood” and its popular fantasy-epic “Game of Thrones. ” Here, in two similar medieval action films and two exceptionally well-made premium-cable TV series, is where the new aesthetic of graphic violence has, for better and worse, reached its fullest expression.

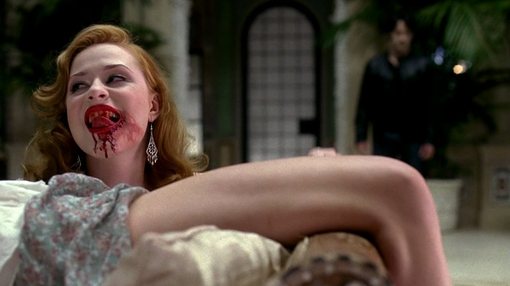

“True Blood” allows characters and viewers alike to get their bloody freak on; it’s easily the most provocative show on premium cable, guaranteed to outrage moral watchdogs with every new episode. On Showtime, we learned exactly how Dexter became “Dexter” from what is arguably the bloodiest, most disturbing murder scene ever televised. “Game of Thrones” announced its stylistic intentions in the first scene of its first episode: Severed heads, limbs, and torsos arranged in a mysterious pattern in freshly-fallen snow — the aftermath of men, women and children sliced to pieces by forest-dwelling marauders of mythological stature. In one shocking, wordless pre-credit sequence, HBO declared itself a major contestant in the new-gore sweepstakes.

So now the zeitgeist has spoken and the new-gore aesthetic, until recently reserved for straight-to-video horror, continues to spill into the mainstream, primarily in dark fantasy and period action movies involving brutal, ultraviolent warfare. In the immortal words of Ving Rhames in “Pulp Fiction” (another milestone in the timeline of cinematic shock value), movies are literally getting medieval on your ass.

Axes, Maces and Mallets, Oh My!

“Ironclad” takes place in England during the period immediately following the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215. King John (played with scenery-chewing relish by Paul Giamatti) is royally cranky after being forced to sign the charter at Runnymede, ceding power and independence to the frustrated, overtaxed land-barons who’ve rebelled against the throne. “What happened next” (as intoned by the film’s ominous narration) is that the petulantly pissed-off king reneges on his promise, forcing barons like Albany (Brian Cox) to recruit Knights Templar (led by the stoically celibate Marshall, played by James Purefoy) to seize control of Rochester, the most strategically located castle in King John’s empire. It’s there that the film’s ultraviolent battles take place, and while history buffs and medieval action fans will kvetch about anachronistic details of weaponry, fighting techniques and liberties taken with established facts, the selling point of “Ironclad” is its violence.

As any seasoned film critic can tell you, some of the film industry’s most creative writing can be found in press materials. This is not a compliment. Production notes are frequently more entertaining than the movies they promote, simply because they’re so shamelessly packed with promotional hyperbole and — no matter how wretched the film being touted — constant emphasis on the supremacy of story and character. To paraphrase a bit from a recent episode of “South Park” (in mocking reference to the current comedy “Zookeeper“), press kits can sell you a turd in a microwave and make it sound like “Citizen Kane.”

The press notes for “Ironclad” provide typical examples of this hype-driven overstatement, but for the most part they’re honest. The film is touted (somewhat accurately) as a medieval “Magnificent Seven.” Director Jonathan English states that he intended to make and “a gritty, pseudo-realistic medieval action movie,” and for better or worse (you can decide for yourselves) that’s exactly what he delivered. “Ironclad” is a film without pretense; it doesn’t claim to be anything more than what it is: A gritty, violent and, yes, entertaining action movie that is nothing if not “pseudo-realistic.” It also happens to feature the severed tongue of a Templar priest; hands and feet chopped off in royal retaliation; skulls bashed in like overripe melons; Marshall’s long-sword thrust through an enemy’s mouth and out the back of his head (accompanied by a spout of blood when the sword is withdrawn) ; and another frenetic battle scene in which one of the good guys picks up the severed arm of a dead enemy and uses it to bludgeon another would-be attacker. With regard to the very-frequent battle scenes in “Ironclad,” one thing you won’t find is any hint of subtlety. You want sheer brutality and graphic aftermath? You got it.

Feel free to condemn “Ironclad” and its ilk, but I’ll say this much in its favor: It’s an action film that delivers its violent payload in the time-honored Roger Corman tradition. Economically produced on a remarkably low budget of $20+ million, it’s an earnestly written and directed film that competes with Ridley Scott‘s historical action epics for pennies on the dollar. There’s good casting, fine acting, and an adequate supply of intelligent dialogue delivered by prestigious Brits like Charles Dance and Derek Jacobi. Seriously, on a Saturday night with popcorn aplenty, what’s not to like?

Perhaps that earnestness is what many critics equate with “bad,” and “Ironclad” is certainly no masterpiece. It’s impossible to watch it without invoking “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” but that only makes it more entertaining. If you’re so inclined, you can turn “Ironclad” into a participatory comedy: You may find yourself yelling at King John’s soldiers to give up and “Run away! Run away!” and you can tell John’s the king because, well, he hasn’t got shit all over him. The parody potential is almost limitless, and Giamatti’s bilious fury is enough to catapult “Ironclad” (along with Cox’s handless, footless corpse) into cult-favorite longevity.

As for the violence, well, it is what it is. Through quick cutting and rapid brutality, “Ironclad” shows it without rubbing your face in it. The genie of gory, realistic battle carnage has been let out of its bottle and it’s never going back. If you’ve been watching “Game of Thrones” and “True Blood” you know that HBO’s brand of gore is sensational (i. e. grand guignol), exploitative and integral to their stories… just not necessarily all three at once. Even for those of us with the stomach for this stuff, you have to wonder, where to from here? Where do we draw the line regarding the realistic depiction of graphic, gruesome violence? The answer is simple: Draw that line according to your own individual tolerance, be it zero or anything-goes. Respectably or not, filmmakers will continue to push boundaries because that’s what they do. Some do it for money, others with a higher sense of purpose. (Here’s a litmus test for you: Is Rob Zombie a trash-monger or an auteur? Can he be both? Discuss.) It all comes back to context and intention, and we’re left with the same, simple choice we’ve always had: Take it or leave it, because it ain’t goin’ away.

Plague, Pestilence and Torture, Oh My!

Like “Ironclad,” the German-made, English-language “Black Death” (also directed by a Brit, Christopher Smith) is an earnest, well-made, independently produced medieval action film, shot in Germany, that boasts the timely appeal of Sean Bean (from “Game of Thrones” and the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy), who’s well-cast in the lead. The year is 1348, and the first wave of bubonic plague is spreading across Europe. Looking battle-weary and filled with dread, Bean plays the seasoned swordsman Ulrich, who leads a band of church-recruited mercenaries to investigate a remote village where it is feared that a necromancer is using sorcery to drive away the plague. The church frowns on that kind of thing, and a young monk named Osmund (Eddie Redmayne), who knows the route the mercenaries must take, volunteers to be their guide.

What Osmund comes to discover, through the movie’s bleak and cynical worldview, is that there are no steadfast distinctions between good and evil when entire populations are struggling to survive. God and Satan are evenly matched, and while the plague-free villagers (led by Carice van Houten, so memorable in Paul Verhoeven‘s “The Black Book”) appear to benefit from some kind of supernatural influence, Dario Poloni’s script combines regular bursts of violence with a surprisingly substantial examination of barbarism among pagans and Christians alike. For anyone who’s curious about rising star Redmayne (who won a Tony award last year for his Broadway performance opposite Alfred Molina in “Red“), the actor handles a complex role with noteworthy nuance. His character’s moral compass is sent spinning by the brutality he witnesses among his Christian escorts, and this ambiguity deepens when the allegedly evil pagan villagers appear to be living in peaceful, idyllic contentment.

The story’s uncompromising coda offers little relief from this crushing weight of moral uncertainty, which probably explains why “Black Death” (like “Ironclad”) was given only a brief, limited release in a few major American cities. (U. S. distributors also shy away from edgy content, modest European box-office and lack of major stars.) And again, there’s the violence: Compared to “Ironclad, ” “Black Death” is a bit more restrained, but it’s got a fair share of blood-spattered mayhem to accompany its defiantly unhappy ending.

As occasionally happens with straight-to-video releases, on-demand access gives films like “Ironclad” and “Black Death” a new lease on life. They’re out there to be discovered by anyone who’s intrigued by their screen-menu poster art and plot synopses (or ignored for the same reasons). “Black Death,” like “Ironclad, ” boasts familiar names and faces in a fine supporting cast (including David Warner and the great Irish character actor John Lynch), and both possess admirably risky qualities that ironically disqualified them from the risky proposition of wide theatrical release. Neither film is a must-see for anyone but medieval action junkies, but they are true to themselves and that counts for something. As for their latest advances in graphic battle violence, well, you can regret it all you want, but it’s realistic and honest in both context and intention, and condemning it requires more than a hint of hypocrisy.

“Ironclad” (121 minutes) is rated R, for strong, graphic brutal battle sequences and some nudity.

“Black Death” (102 minutes) is rated R, for strong, brutal violence and some language.

_ _ _ _ _

A Seattle-based freelancer, Jeff Shannon has been writing about film and filmmakers since 1985, for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (1985-92) and The Seattle Times (1992-present). He was the assistant editor of Microsoft’s “Cinemania” CD-ROM and website (1992-98), where he worked with rogerebert.com editor Jim Emerson, and was an original member of the DVD & Video editorial staff at Amazon.com (1998-2001). Disabled by a spinal cord injury since 1979 (C-5/6 quadriplegia), he occasionally contributes disability-related articles to New Mobility magazine, and is presently serving his second term on the Washington State Governor’s Committee on Disability Issues and Employment.