When it comes to the secular ambassadors of Christmas, only Santa Claus beats Bing Crosby as being synonymous with the holiday—but just by a whisker or two.

Of course, Jolly Old St. Nick basically really only has two claims to fame: Delivering presents one night a year and having a prodigious appetite for milk and cookies. Der Bingle, meanwhile, brought so much more beyond just a sack of goodies to his legions of fans.

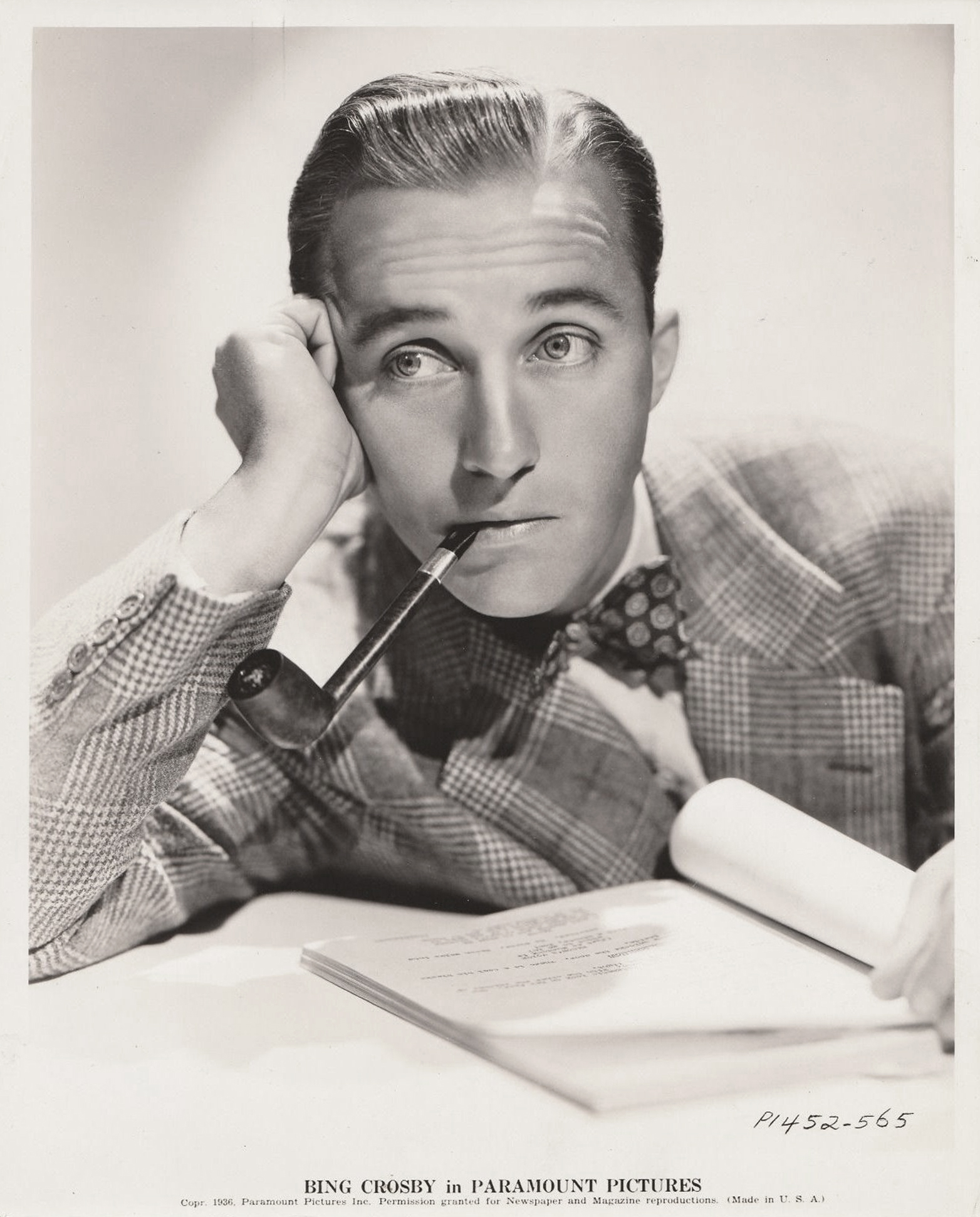

As recounted in the fascinating documentary “American Masters: Bing Crosby Rediscovered,” which premieres Tuesday night on PBS stations and has an encore presentation on Dec. 26, the mellifluous laid-back crooner was a multi-media pioneer who conquered radio, music, movies and TV. With 400 hit singles—including more No. 1 recordings than any other artist—and a best-actor Oscar for his Father Chuck O’Malley in 1944’s “Going My Way,” Crosby’s involvement in the entertainment industry spanned more than 50 years until his death in 1977 at age 74.

But if anyone under 30 knows his name these days, it is probably because of that unavoidable yuletide chestnut, “White Christmas.”

He introduced the Irving Berlin-penned song on a Christmas Day radio broadcast in 1941 and it remains the top-selling single of all time. According to Guinness World Records, Crosby’s recorded version—first performed in the 1942 film “Holiday Inn” and later re-recorded in 1947—has sold more than 100 million copies worldwide, with an estimated 50 million as singles. It also won the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

But music is only part of the reason that Crosby remains as linked with the season of giving as fruitcake and eggnog. Besides traditional yearly re-airings of 1954’s “White Christmas,” his most popular movie, the enduring star also appeared in holiday-themed TV specials right up until the end.

For Crosby, being associated with Christmas was always more of a blessing than a burden. “Whenever he was asked about it, he would say, ‘What is the down side? It’s a wonderful holiday and everyone is in a great mood,'” says Robert Trachtenberg, who wrote, directed and produced the PBS documentary.

The beloved entertainer’s snow-white public image was somewhat tarnished after Gary Crosby, his eldest of four sons from his first marriage, wrote a 1983 “Daddy Dearest” tell-all memoir that chronicled a childhood full of harsh physical punishments. A dark cloud was cast over his father, who was considered a dutiful family man, a devout Catholic, an upstanding citizen and loyal friend to such stars in need as Judy Garland and “White Christmas” co-star Rosemary Clooney.

As Trachtenberg’s doc points out, the Crosby home was often not a happy one. First wife Dixie, an actress and singer who died from ovarian cancer at age 40 in 1952, struggled with alcoholism throughout her life and twin sons Dennis and Phillip were most likely victims of fetal alcohol syndrome.

Crosby was a caring man but he could be a cold and distant father, one who struggled to say the words, “I love you.” Renowned jazz critic Gary Giddins, author of the definitive 2001 Crosby biography, “A Pocketful of Dreams,” who is working on a second volume that picks up in 1940, confirms that the household “could be a hellish one in a lot of respects. That was the way Bing was raised, with a hairbrush.”

As for whether his son’s accounts of constant cruelty and harsh disciplinary action were all true, Giddins—who contributed to the documentary and appears in it—says, “I have nine hours of Gary on tape and he softens quite a bit from what he wrote in the book. When I asked him about specifics, he would reply, ‘I don’t remember. I was drinking at the time.’ His brothers have denied a lot of what he wrote. I interviewed over 300 people and I never heard a negative word from fellow actors, producers and musicians.”

Complicating matters was that Crosby’s second wife and their three children did not issue any public statements of denial at the time. “They stayed under the radar, because that was the way he always handled the press.” The documentary lends some much-needed perspective on the portrait painted by the book, one that still lingers in the minds of many.

Despite their problems, though, Crosby’s first family managed to celebrate Christmas in style. “They threw big parties for the Hollywood community,” Giddins says. “They always had a big tree.”

Unfortunately, in the early days of 1943 shortly after the song “White Christmas” first became a huge hit, the Crosby home burned down after the tree’s lights sparked a fire. “No one points out this incredible irony that his house was destroyed by a Christmas tree,” Giddins says. “Two or three days into the new year, they were dismantling the tree. They lit it one more time and it started a five-alarm fire. Everyone got out, but they lost almost everything. After that, they made sure their tree was fireproof.” Even that devastating event did little to dampen Crosby’s holiday spirit over the years.

How Bing and Christmas became intertwined.

Through music and radio: The first Christmas songs that Crosby ever recorded were “Silent Night” and “Adeste Fideles” (“O Come All Ye Faithful”) in 1935. He was reluctant to release such religious songs commercially and gave the money he earned to charity, Giddins says. He would later re-do the two carols in 1947 for an increased royalty.

The idea for re-issuing records seasonally came from Decca record executive Jack Kapp, who brought back Silent Night in 1940. “It sold just as well the second time,” Giddins says. “He would re-release it every Christmas.”

When it came to “White Christmas,” “No one thought it would be a big hit except for Bing,” he says. “Kapp decided to pair it with another song from Holiday Inn, “Let’s Start the New Year Right.” No one saw sales like that before. It was like the Beatles in the ’60s. It changed the industry.” And, just like “Silent Night,” it would be re-issued regularly.

One of the reasons for the great success of “White Christmas” was timing. By 1942, the country was fully engaged in World War II and many soldiers would not be home for the holidays. “Irving Berlin wrote it as a war song,” says Giddins. “It is probably the first war song that didn’t mention the war. It became an anthem.”

During that time, Crosby dedicated himself to going overseas and entertaining the troops. “The song cemented the relationship he had with the soldiers,” says Trachtenberg. “Crosby was already working his butt off everywhere and anywhere. This song comes along and it feels like home for them. “

Crosby also introduced another holiday classic that had similar sentiments in 1943: “I'll Be Home for Christmas.” Again, it was a hit with the troops. “No one did more for the war effort than Bing Crosby,” Giddins says. “Bob Hope did for the rest of his life, but that was after Bing had had enough.”

There are numerous album collections featuring Crosby doing holiday standards. But the biggest seller, originally titled “Merry Christmas,” came out in 1945 and was renamed “White Christmas” in 1995. Never out of print, it has sold more than 15 million copies—enough to make it the second best-selling Christmas collection of all time next to Elvis’ 1957 holiday album, which sold more than 19 million copies.

In the movies: “Holiday Inn” might have introduced White Christmas. But as far as movie-musical plots go, this story set at a New England hotel that is only opened on holidays has a not-so-merry cynical streak as Crosby and co-star Fred Astaire scheme and plot to upstage one another and steal each other’s girlfriends.

The song pops up in another big-screen Crosby-Astaire collaboration featuring Berlin songs, 1946’s “Blue Skies,” where the pair once again vie for the affections of the same woman.

But “White Christmas,” the highest-grossing hit of 1954 that is marginally a remake of “Holiday Inn,” has a sentimental streak as long as Santa’s yearly trek around the world from the North Pole. Paramount recently released a special diamond anniversary edition Blu-Ray and DVD to celebrate the movie’s 60th anniversary.

Just like the song, “White Christmas” is military-inspired as former World War II soldiers—led by Crosby and his performing partner played by Danny Kaye—reunite to pay tribute to their retired general. “It is really about Korea,” says Giddins. “It’s a replay of the anxiety found in World War II pictures.”

Even though Crosby is heard on the documentary expressing disappointment in the storyline of the film directed by Michael Curtiz of “Casablanca” fame, he nonetheless formed a close bond with his onscreen love interest Clooney for the rest of his life.

“He made the film during one of the worst years of life,” Giddins says. “It was after his first wife died and he was suffering from depression. He went through a difficult period and even threatened to retire. To compensate, “He went through the entire chorus line and dated every woman in the film. Look for one dancer, a tall blonde, who gets a lot of close-ups.”

Still, Crosby does have a point about the plot. Giddins’ own wife is not alone in her complaint that Clooney’s character Betty spends the movie going out of her way to find fault in Crosby’s Bob even though she clearly loves him. “She thinks Rosemary is so stupid in the film. We had her over for dinner and she asked Rosemary, ‘Why are you constantly taking umbrage and having fights with him?’ She explained that during the first week of filming she walked over to Curtiz and asked why Betty was acting like such a moron. He said, in his German accent, ‘If you don’t, there is no movie.’”

Another Crosby outing that often gets seasonal replays is 1945’s “The Bells of St. Mary,” a sequel to “Going My Way” in which his priest butts heads with Ingrid Bergman’s Sister Superior. A Christmas pageant scene that was mostly improvised by the child actors is one of the film’s highlights.

On TV: In his later years, Crosby took full advantage of the medium of television as a way to reach out to a new generation. That included stints as host of “The Hollywood Palace” variety show from the ‘60s, including Christmas editions that featured second wife, Kathryn, and their three young children, Harry, Mary and Nathaniel.

Crosby also did his own network holiday specials that aired in 1961, 1962 and 1969-77. But it was his final Christmas show, which was shot in England and aired in November 1977 about a month after his death, that is most remembered primarily for a duet shared with an unusual guest: David Bowie, 30, best known at the time for his glam-rock alter ego Ziggy Stardust.

Their performance of “The Little Drummer Boy,” which would become a perennial on Christmas-themed radio stations and as an Internet video clip after being released as a single in 1982, was almost derailed after Bowie said he hated the carol and would not sing it. The songwriters associated with the special quickly penned a counter melody for him instead, “Peace on Earth.” Bowie, who only did the show because his mom adored Crosby, agreed and a strangely magical pop-cultural moment was born.