“Gotham’s time has come. Like Constantinople or Rome before it, the city has become a breeding ground for suffering and injustice. It is beyond saving and must be allowed to die. This is the most important function of the League of Shadows. It is one we’ve performed for centuries. Gotham… must be destroyed.”

— Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Watanabe), “Batman Begins” (2005)

“Over the ages our weapons have grown more sophisticated. With Gotham we tried a new one: economics…. We are back to finish the job. And this time no misguided idealists will get in the way. Like your father, you lack the courage to do all that is necessary. If someone stands in the way of true justice, you simply walk up behind them… and stab them in the heart.”

— Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson), “Batman Begins” (2005)

“You see, their morals, their code, it’s a bad joke, dropped at the first sign of trouble. They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these civilized people, they’ll eat each other.”

— The Joker (Heath Ledger), “The Dark Knight” (2008)

“Terror is only justice: prompt, severe and inflexible; it is then an emanation of virtue; it is less a distinct principle than a natural consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing wants of the country.” — Maximilien Robespierre, 1794

“I am Gotham’s reckoning… I’m necessary evil…. Gotham is beyond saving and must be allowed to die.”

— Bane (Tom Hardy), echoing his former master in “The Dark Knight Rises” (2012)

– – – – –

(You’ve seen “The Dark Knight Rises” by now, right? Good. I’m going to discuss a few things that I would consider spoilers, albeit mild ones, and then get to some pretty big spoilers later on, before which I will offer an additional warning, just in case.)

– – – – –

The villains of Christopher Nolan’s “Batman” movies don’t think very highly of “ordinary citizens” (now popularly referred to as “the 99 percent”), whom they tend to view as mindless savages, slaves to fear who’ll claw one another and the city of Gotham to shreds at the slightest provocation. The films themselves sometimes confirm that view (Gothamites get a little panicky in “The Dark Knight” when they fear that Batman is not keeping the crime rate down) and sometimes don’t (they choose not to blow themselves up in the Joker’s intricately planned ferry experiment). This isn’t really a theme that’s developed in the movies, but like most of the political and social references, it’s something that’s… there.

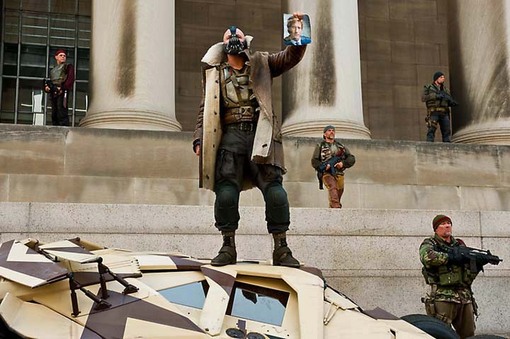

In “The Dark Knight Rises,” brawny masked supervillain Bane, a League of Shadows reject not unlike Bruce Wayne (Wayne parted ways with Ra’s al Ghul over a ritual judge-jury-executioner beheading), is a “Road Warrior” Robespierre who says he wants to return power to the people and let them administer justice on their own terms. Those terms include placing “Judge” Jonathan Crane, aka Scarecrow (Cillian Murphy), on top of a mountain of desks that belong in a production of Kafka’s “The Trial,” dispensing the people’s instant justice: “Death or exile.” (Guess what? They both turn out to be the same thing.) Really, of course, Bane just intends to blow them up. Like all the differentiated characters in Nolan’s movies, he’s got a plan.

The third and final act of Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy plays out on a broader social canvas than its predecessors. The screenwriters Nolan, brothers Jonathan and Christopher (with David S. Goyer sharing story credit), have cited Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities” as their inspiration, and the film invokes the French Revolution and the populist Occupy movement that sprang up in the aftermath of the financial meltdown of 2008 (just a few months after the release of “The Dark Knight”). Again, the movie doesn’t do much with any of that; it’s more like a backdrop.

You’ll recall that there was a lot of talk about economic depression, the rich and the poor, in “Batman Begins.” Bruce Wayne’s philanthropist parents are, as R’as al Ghul says, “gunned down by one of the very people they were trying to help. Create enough hunger and everyone becomes a criminal.” In “TDKR,” this gap between the haves and the have-nots is one of the motifs that’s brought full circle to conclude the trilogy. (A quick aside: I don’t feel it’s appropriate for me to comment or speculate on the shootings in Aurora, CO. There’s been more than enough of that already.)

“Batman Begins” was an origin story, about how the personal crises of Bruce Wayne and the civic crises of Gotham gave birth to “the Batman,” an anonymous vigilante-justice figure (in Part 3, Bruce repeatedly emphasizes that “Batman could be anybody” behind the mask) who was more effective as a legend than as an individual. In “The Dark Knight,” the Joker sets out to unmask and identify Batman, to rob him of his symbolic power, and to complete the civilization-collapsing work R’as al Ghul started (though, as a flaming narcissist, the Joker isn’t so good at giving others credit where it’s due), while the film itself assumed a more propulsive, action-movie form. “The Dark Knight Rises” goes wider as a (murky) social fantasy-parable, but the main players are still the designated power elite — no regular Joe heroes, though a young street cop named John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) with a childhood connection to Bruce Wayne rapidly rises to become Commissioner Gordon’s (Gary Oldman) right-hand man. The battles for the soul of Gotham are mostly fought by the masked gods and demigods. The street-brawling of the wretched masses is just an expression of the higher-ups’ will.

(Next-level spoiler warning)

We’re told that, over the last eight years since the Batman took the fall for the crimes of Harvey Dent, crime in Gotham has been virtually eliminated. (This being a Nolan comic-book movie, all actions are carefully plotted in advance. There is no room for accident or coincidence or spontaneity. Or air. Apparently only rigidly organized crime was ever a problem in Gotham.) Dent has become a secular saint, and Batman has… disappeared from public view, and from the imaginative life of the city. One cop, named Foley (Matthew Modine), shows a determination to get the “killer” of Harvey Dent, but although Batman has apparently been demonized, by now everyone seems to have pretty much forgotten about him. When he does show up again, we don’t see much of a reaction from the public or the rank-and-file police. (I appreciate the way Foley is disposed of: he dies like an extra, just another cop, which is fitting.)

Now I’d like to get this out of the way: I’ve criticized Nolan’s previous films (particularly “Batman Begins,” “The Dark Knight” and “Inception“) for being statically directed and turgidly written. Speaking only for myself (as always), I think “The Dark Knight Rises” is a marginal improvement on both those fronts. Yes, the screenplay is still overloaded with mere keywords (mask, plan, fear, justice, hero, hope…), like a first draft that needs to be fleshed out. Yet, based on my single viewing, it feels like there are fewer repetitive theme-statements and expository lectures/speeches this time.

Some, at least, of Nolan’s shots have been designed to last longer, are somewhat less flatly composed (if I remember correctly, Bruce Wayne appears in a nicely distorted reflection in a silver lid), and some even contain more than one person at a time. What’s more, those people interact within the shot! That’s a huge deal for Nolan, who ordinarily doesn’t visualize in three dimensions. As far as I’m concerned, these are notable steps forward in Nolan’s development, even if they remain few and far between, because they are the kinds of thing I enjoy most about movies: how imaginatively they create their worlds visually and audibly, from moment to moment.*

As for the vehicle chases, I never felt as disoriented as I did during the big “Dark Knight” lower-level convoy pursuit, perhaps because the action here is more streamlined. (Preparation must also have been more thorough than in the last one, because at least I wasn’t significantly bothered by spacial-orientation problems the first time through — but I’d given up expecting coherent grammar from these films, anyway.) There are even a few (intentional?) reminders of Buster Keaton (involving streets crammed full of cops — in vehicles with flashing lights, and later on foot and in uniform), though without the earlier filmmaker’s visual/philosophical eloquence.

The movie opens with a spectacular aerial stunt sequence made for IMAX — like the outrageous gag opening of a Roger Moore 007 picture [readers point out it bears the closest resemblance to another 1980s Bond, “License to Kill” with Timothy Dalton], or one of the James Bond “dreams” from “Inception.” The climactic stunt at the end recapitulates it (something is tethered to an aircraft) and, I’m happy to say, the similarity is there for you to notice or not notice. Nobody’s around to explain it or draw the connections for you. (Not that the connection means anything; it’s just a visual rhyme.)

I know some have complained about Bane being unintelligible, and the injustice of hiding Tom Hardy behind a mask that looks like a steampunk version of the tumor growing on Robert Silverman’s throat in David Cronenberg’s “The Brood” (“That’s Psychoplasmics!”). But I think he’s the perfect villain for this film, and particularly for Nolan: He gives a few speeches to crowds, but for the most part, you have to read his character in his eyes. And that’s a good thing, because he doesn’t have the full range of expressions to spell everything out for the audience (though another character does some heavy explaining on his behalf near the end), so he has opportunities to draw emotions out of us. That’s part of the function of his mask: not to conceal his identity, but to provide a figure onto whom others can project their fears.

Recently, I wrote something about “Prometheus” in which I mentioned that, when a movie shows blatant disregard for story logic, it may be a (bat-)signal that it means to be read on some other level. That’s definitely the case here. On the level of plot, it’s as preposterous and irrational as any of its predecessors, maybe more. But Nolan is more interested in implanting thematic ideas — even if he doesn’t do anything with them. The larger ones, about the nature of mobs and civilization and democracy and economic injustice, aren’t dramatized, just checked off the movie’s list of topics.

But some character arcs are nicely shaped (though they’re still more arc than character) and, even if they make little sense in terms of actual plot or psychology, at least feel satisfying on an abstract or vaguely emotional level. (“You who had an ark? Noah.” — Sal “Big Pussy” Bonpensiero, “The Sopranos.”) In that sense, this is the lightest of the Nolan Batman pictures. Not only does it feel to me that more of it takes place in broad daylight, and the overall tone seems marginally less grim and heavy-handed (the possibility of nuclear annihilation aside), but there are amorous and romantic glimmers that haven’t been allowed into Nolan’s Gotham before — even among the “villains.” The damn thing even has a more-or-less conventionally romantic happy ending. And stylish catburglar Selena Kyle (Anne Hathaway) is the first Nolan Batman character with a playful, insouciant sense of humor.

So, let’s put those standard reservations about Nolan’s writing and direction aside. He prefers to approach movies as if they were puzzles or games. His production company, Syncopy, has a maze for a logo. Although he’s a narrative classicist in many ways, he isn’t so much interested in conventional notions of character, writing, storytelling or direction. He likes to build intricate boxes, gadgets, that operate by their own stipulated rules. He meticulously constructs them one little piece at a time, as if he were building the “architectural dreaming” contraptions of “Inception” with mosaic tiles. He explains the rules (though not in “The Prestige“), places his characters and his audience inside, and then puts them through their paces.

I haven’t read other full reviews yet, but I’ve seen indications that people who really loved “The Dark Knight” are less satisfied with “TDKR” than those who found much to fault in the first two. I can see how that would be. I mean, if you already feel that “TDK” must be “the best movie of all time” or some such thing, what could compete? I think “Batman Begins” and “The Dark Knight” are mediocre movies (details here), and “TDKR” represents a small but measurable improvement in several respects. So, yeah, if you’re looking for the *like*/*dislike*: I think that, in comparison to its predecessors, it’s the better of the three.

In the end, what really interests me is the notion the trilogy began with, that people can be inspired by (and lawbreakers will fear) a legend, a symbol, an abstraction, in ways they can’t respond to a mere human being. “TDKR” is a superhero movie that acknowledges “heroism” is primarily a form of public relations, of marketing and branding. When Batman decides to take the fall for Harvey Dent’s crimes at the end of “TDK,” Jim Gordon delivers the movie’s closing soliloquy: “… he’s the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now. So we’ll hunt him. Because he can take it. Because he’s not our hero. He’s a silent guardian, a watchful protector. A dark knight.” And yet, we now learn, Batman promptly disappeared in the gap between movies — not at all a silent guardian or watchful protector. Dent became the hero, even though his heroism was a lie foisted upon the public by Gordon and Batman, ostensibly to preserve civic morale. (That never made much sense to some of us: I guess it was because Batman didn’t want to give the Joker credit for destroying Dent, feeling that might be too demoralizing and dispiriting for the general public. But is it too much to show the citizenry why they have been wrong about Batman? Couldn’t Batman have played the role of hero, having foiled the Joker, and Dent become the fallen martyr, his crimes pinned on the Joker? Frankly, I don’t remember the plot holes very well…)

In “TDKR,” Batman’s reputation is redeemed. (Though why anyone should believe Bane’s reading of Gordon’s undelivered, history-correcting speech, I don’t know. Does this silver-studded leather hulk seem like a trustworthy source of information to you?) And then he achieves his destiny as a false martyr. He gets his Bat-statue in City Hall (or wherever that is), and he gets his personal life back. The argument (from Alfred, anyway), is that Bruce Wayne has done enough; he’s sacrificed much of his life to the greater cause, even if he did not literally sacrifice his life in the nuclear explosion from which he saved Gotham. So, Batman’s — and, by extension, Bruce Wayne’s — newly redeemed status is based on a big lie, another deception, that allows him both public glory and an escape to private freedom and blessed anonymity. Like the magic tricks in “The Prestige” or the dream architecture of “Inception,” heroism is an illusion, a con designed to fool a willingly gullible audience. “You want to be fooled,” claims Cutter (Michael Caine) in “The Prestige.”

At least there’s no last-minute supernatural cheat this time. Fantasy elements notwithstanding, the appeal of Batman has always been that he relies on science-fiction technology, not superhuman powers. Without his suit and his gadgets, he’s just a person — and Nolan underlines that with the refrain about how Batman could be anybody, which is the source of his strength as a legend. At the end of “TDKR,” the torch is passed to the next generation. Another reboot is inevitable. What kind of hero will we need, or deserve, next time?

_ _ _ _ _

* As I’ve detailed before, a typical Nolan shot consists of one thing, isolated in the foreground, that is in the frame at the beginning of the shot and is still there at the end (unless, perhaps it’s an entrance or an exit from a scene). The point being that during the course of a shot, it is rare that something will enter or exit the frame, or that there will be significant interaction between the right and left, foreground and background. He makes fairly static images, unless they’re helicopter or crane shots, in which case the emphasis is on large vistas, stretching into the distance. Those are generally spectacular. And at least Nolan uses real cameras in real helicopters flying through real airspace in real light (or darkness), rather than just simulating the whole thing in a computer. Still, Nolan has often substituted scale for grandeur. Awe and IMAX are not the same thing.

UPDATED (07/23/12): Adapted from my response to a comment below:

I have no doubt that Nolan is doing what he’s doing deliberately, because this is the way he does it (or likes to do it). Maybe it’s ineptitude, but I don’t think so. I’m inclined to think that he’s an artist who creates his film-worlds the way he wants to create them. I’ve never been terribly impressed, but that’s where values and preferences and tastes come into it.

Whether it’s a simple dialog scene between two people in a room, or a big action set-piece, his approach leaves me unexcited and unmoved (for all the many, many reasons I’ve explained over the last however-many years). I think Keith Uhlich said it well, in a discussion of “TDKR” with Mike D’Angelo at IndieWire:

I wish I could say that Nolan gave his characters’ tendency toward expository verbosity the proper comic-book kick, so that we might imagine thought-balloons sprouting. But I feel little besides ponderous, minutely planned-out portent, and sense in just about everything he’s done a distinct absence of poetry–of that intangible essence that truly great art and artists possess.

That lack of feeling for poetry, for experience, for the sensations of being alive in/to the world, is sorely missing from his rather crimped, schematic movies. They’re re-animated; there’s no soul in them.

And, for another compelling and insightful point of view that is often antithetical to mine, do read Bilge Ebiri on Nolan and the Dark Knight Trilogy. Here’s something Bilge wrote about the ending that I quite support — in part because (in my view) it shows up the phoniness of the ending of “The Dark Knight” before it:

And when you think about it, Batman’s final sacrifice is a reversal/redemption of Harvey Dent’s “sacrifice” from “The Dark Knight.” Gotham has been told that Dent died a hero at the hands of Batman, setting an example of rectitude and nobility that has been used to enact new laws that have kept criminals off the streets. This has eaten away at the heart of Commissioner Gordon (Gary Oldman), not just because it’s a lie, but also because it has established a false sense of hope. In some ways, it’s almost as bad as Bane’s prison – just as the prisoners live in a world where they’re confronted every moment by a freedom that doesn’t exist, the citizens of Gotham live in a world justified by a sacrifice that never happened. Batman’s final sacrifice is a correction of that lie, and it replaces that false hope with a genuine one.

Of course, we could call this sacrifice a lie, too, since Bruce Wayne does get to live. But in both The Dark Knight and in this film, Nolan goes out of his way to represent Bruce and Batman as two distinct characters. (There’s a notable scene in the earlier film, when Batman shows Morgan Freeman’s Lucius Fox the elaborate, very illegal, and deeply unethical citywide sonar he has created out of Gotham’s cellphones; pointedly, even though Fox knows his identity, Bruce does this dressed as Batman, complete with his deep, growly “Batman voice,” establishing the fact that when Bruce is in the Bat-suit, he is for all intents and purposes a different person.) This is also where The Dark Knight Rises’ references to Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities play out most poignantly, since that novel ends with one character sacrificing himself so that another, his lookalike, may live on in happiness. Make no mistake, the hero’s death at the end of “The Dark Knight Rises” is very real. And it is perversely “hopeful”- with all the ambiguity that implies.

I always thought the ending of “The Dark Knight” was not the noble sacrifice it was made out to be. Basically, it was Gordon and Batman deciding that the citizens of Gotham “can’t handle the truth” (in Aaron Sorkin language), so they contrive to preserve Harvey Dent’s image at the expense of Batman’s — when they could have explained what really happened and restored Batman’s previously heroic reputation among the citizenry. (The Joker’s contention that, somehow, Batman was making the city crazy — and was even responsible for the craziness of the Joker himself — was never the slightest bit convincing, just a device dictated by the plot. If Gothamites believed that, they’d believe anything.)

In fact, Dent is a smug, corrupt DA from the beginning (putting 549 rounded-up crooks on trial at once with the cooperation of a renegade judge) — and Rachel, Gordon, and everyone else in city government knows it. The mayor says it’s a “farce” and that the only reason Dent might be able to pull it off (forget legalities) is that “the people” like him. We’re just supposed to take that at (two-)face value — but if the Gotham media and populace are willing to let their DA run wild, then they deserve whatever chaos they get. Were a long way from the Rachel of “Batman Begins” telling Bruce Wayne: “Justice is about harmony. Revenge is about you making yourself feel better, which is why we have an impartial system.” Harvey Dent is the enemy of that system. The Joker probably does more to fight crime than Dent does. At least he deprives the kingpins of their money, rather than just putting a bunch of low- and mid-level crooks out of circulation for a few months on charges that won’t stick because they haven’t been properly brought. Also, Dent claimed in public that he was Batman, so he obviously lied to the people of Gotham about that before he was kidnapped and turned into Two Face — after being rescued by the real Batman. How much does the public know about that? They never see Two Face. Do they think he was killed by the Joker — either when Rachel was killed or in the hospital explosion? Why would people think Batman killed him, when he was last seen in a police van under attack by the Joker?

Also, as I pointed out above, after the events of “The Dark Knight,” Batman ceases to become important — as a hero or a scapegoat. He simply disappears. In “The Dark Knight Rises,” we finally learn that was actually at stake in the story at the end of “The Dark Knight” had little to do with the citizens’ need for heroes, and more with Bruce Wayne’s illusions of Rachel, based on a big lie that Alfred perpetuated in shielding Master Wayne from the truth. Only the truth about her letter, belatedly revealed to Bruce even though Alfred burned the letter itself, can begin to restore the proper balance — in Bruce’s psyche, that is. So, in the end (as I also observed in a comment below), Bruce Wayne sacrifices Batman so that the real Bruce Wayne can live. The roles are reversed: It’s no longer Batman who is the true Bruce Wayne, but Bruce Wayne who is freed from the legacy of anger and guilt and shame that led him to become Batman.

ADDENDUM (07/24/12): I’m not sure Nolan is so imaginatively thorough, but this is perhaps the best capsule description of his methodology that I’ve seen — again, from Bilge Ebiri

He doesn’t tell novelistic tales full of generously detailed characters. Rather, he takes a single idea and works it from practically every angle, so that the idea becomes almost a cipher to unlocking the film itself.

Bilge appreciates that single-mindedness more than I do.

ADDENDA (07/25/12): In an interview with Rolling Stone, Nolan confirms my impressions of how he incorporates political material into his films:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. What we’re really trying to do is show the cracks of society, show the conflicts that somebody would try to wedge open. We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story. If you’re saying, “Have you made a film that’s supposed to be criticizing the Occupy Wall Street movement?” – well, obviously, that’s not true. […]

If the populist movement is manipulated by somebody who is evil, that surely is a criticism of the evil person. You could also say the conditions the evil person is exploiting are problematic and should be addressed. […]

The corruption that drives Bruce Wayne to become Batman is very extreme. So, you know, your concept of “Does the end justify the means?” shifts according to the backdrop. And so the challenge of “Batman Begins” was to make us OK with the idea of vigilantism. The films genuinely aren’t intended to be political. You don’t want to alienate people, you want to create a universal story.

And, from an admiring overview of Nolan’s career at the BFI site, written before “TDKR” was released:

[Nolan’s films] dissolve the boundaries between a populist and a private cinema. The epithet ‘fanboy’, thrown around derisively by critics and filmmakers assailed by the web hordes, may be the key to understanding Nolan. The director is arguably both the fanboy’s fanboy and the redeemer of that derogatory tag, able to wrest the wonder of adolescent imagination back from the cynical and the hyper-critical. […]

How you react to Nolan’s recent work depends on the degree to which you consider the term ‘adolescent’ to be pejorative; certainly, there’s an inhuman blandness to the Nolan dream-landscape – an unworldly, sexless atmosphere. In “Inception,” the arrival of gun-toting goons in the target’s dream prompts the comment that the target’s “subconscious has been weaponized”. The line might suggest an untamed id gone wild, but the result is in fact a radical reduction of possibilities to machine guns, explosions and car crashes. The subconscious here has been infantilised.

This Peter Pan-like sense of never growing up is reflected in his choice of actors. Leonardo DiCaprio, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Heath Ledger and Christian Bale were all child actors, and they present a boyish, svelte and resolutely un-blokeish masculinity. Nolan’s preferred male characters are all techno-savvy fussy dressers. […]

But if Nolan’s work is refreshingly light on machismo, it has little place for complex female characters either. Women remain stuck in the original archetypes of the femme fatale, the victim or the doe-eyed ingenue…. Nolan’s women, it seems, are only to be longed for, mourned or mistrusted. […]

Escapism is both Nolan’s greatest strength and a point of weakness, because it could be read as a refusal of any radical action in the real world. The closing words of “The Dark Knight” – “Sometimes the truth isn’t good enough. Sometimes people deserve more” – could stand as that film’s argument, and indeed Nolan’s mission statement as a whole, but it could also be seen as a reactionary sentiment in a film that presents the general public as a dangerous mob of complainers only seconds away from panic and murder, who in order to avoid chaos must be manipulated by politicians, policemen, heroes and millionaires. As Slavoj Zizek has pointed out, “The Dark Knight” is an expression of “the undesirability of truth” – as good a definition of escapist entertainment as one might wish for.

And indeed the ‘undesirability of truth’ can be seen as Nolan’s key theme, addressed in all his films – its roots lying in a fear of what might occur when the fragile codes that stop (in the Joker’s phrase) “civilised people from eating each other” are broken. Those who violate these codes have been figures of fear in his work since the start. “Following” was influenced by Nolan’s experience of having his London flat broken into; “Memento” is a nightmare about the loss of control, as is “Insomnia“; “The Dark Knight” is about the sacrifices necessary to maintain control. The thuggishly villainous figure of Bane (Tom Hardy) in “The Dark Knight Rises” is another embodiment of this fear.

Guarding against this loss of control often entails moral compromises. Nearly all of Nolan’s films include a scene where the heroes entrap and torture antagonists in order to achieve a moralised goal. Nolan seems to suggest that it’s a human being’s ability to fictionalise himself – to practise a performative morality, to make themselves into whatever they need to be – that redeems them. This self-realisation involves a choice. […]

In Nolan’s films the only hope seems to be the hope of escape.

“The Dark Knight Rises” overturns or at least questions some of these themes from earlier Nolan films, which is one sign, I think, of growth.