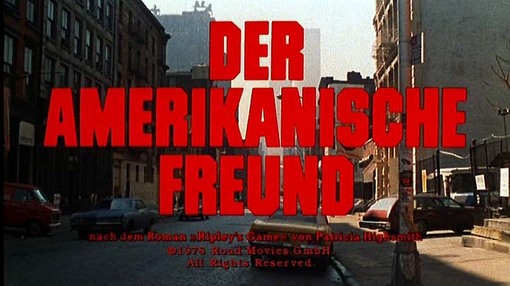

The opening shot of Wim Wenders’ moody color noir “The American Friend” (1977), based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1974 novel “Ripley's Game,” isn’t anything fancy or complicated — no intricate tracking or crane movement — but, wow, does it announce the movie. First we hear the sirens and the traffic noise behind a black screen, over which the title is immediately emblazoned in electric red-orange block letters: “DER AMERIKANISCHE FREUND.”

Bam! We’re there, at street level on the lower West Side of Manhattan. We get a look at a few cars and a truck heading uptown, and the ghostly outlines of the World Trade Center towers that stand in the distant haze — modern New York looming over this less imposing block of old New York. (They also provide a Roman numeral II to mark this sequel to the Scanners Opening Shot Project, which is why I chose this shot for last week’s announcement of Part 2).

The title is wiped off the screen by the arrival of a taxi, entering the frame from the left behind the camera. The cab seems to glow in the shadows, as if from the residual illumination of the title lettering, but we see in the window reflections that the orange light is radiating off the facade of the building out of frame to the right.

There’s movement in the back seat and a man in a cowboy hat emerges, hugs his jacket to his chest, and gives us a brief moment to register his silhouetted face. It’s Dennis Hopper as Highsmith’s criminal sociopath, Tom Ripley. At this point in Hopper’s career — two years before his turn as the wigged-out photographer in “Apocalypse Now” and eight years before his big-splash return to American film consciousness in David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet,” Tim Hunter’s “River's Edge” and David Anspaugh’s “Hoosiers” (for which he got an Oscar nomination), the actor himself had become something of a shadowy presence in movies. (He spent most of the 1970s in Taos, consorting with drugs, booze and guns, and later claimed he couldn’t remember much of that decade, and didn’t want to.)

It’s hard to tell from this glimpse if Ripley is cold, nervous, in pain, or all of the above. (We soon see he’s definitely suffering from some existential anxiety.) The camera pans with him as he walks into the building at right. Before he exists, we hear a rough voice singing a kind of a cappella blues. Cut. Inside, a man is waiting. A solitary red lightbulb seems to carry over the glow from outside into this bluish interior. This is the man Ripley has come to see. We don’t know his name yet (we don’t know Ripley’s, either), but he is Derwatt, a “dead painter”/forger played by the great American director Nicholas Ray (“They Live By Night,” “On Dangerous Ground,” “In a Lonely Place,” “Johnny Guitar,” “Rebel Without a Cause,” “Bigger Than Life”) — who directed Hopper in “Rebel” and would co-direct (with Wenders) the documentary “Lightning Over Water” (1980) about his attempt to make a final feature before his death from cancer.

As convoluted as the twists of “The American Friend” may seem (Roger Ebert wrote that Wenders had tossed out the parts that would help it make plot sense, challenging us “to admit that we watch [and read] thrillers as much for atmosphere as for plot”), it opens and closes with conventional bookend shots: of a man coming into the frame, and then of a man walking away. Of course, they’re not just “conventional” shots, because they’re photographed by Robby Müller, one of the great cameramen of the New German Cinema (along with Michael Ballhaus, Thomas Mauch, Jürgen Jürges).

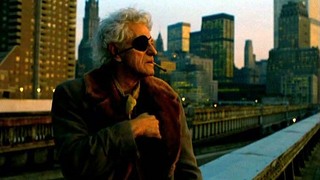

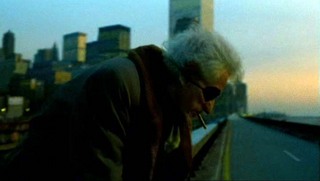

In the final shot, Derwatt is again waiting for someone… who does not arrive. In the deepening dusk, he walks off down the road, this time with another New York landmark — the Statue of Liberty* — outlined against the dying light. It’s a fittingly inconclusive ending for a most melancholy thriller, a movie about alienation and isolation, images and illusions, forgery and frames, in which, as one character says, “friendship isn’t possible.”

“I know less and less about who I am… or who anybody else is…. Even this river… this river reminds me of another river.” — Tom Ripley

– – – – –

Another good adaptation of “Ripley’s Game” appeared (under that title) in 2002, directed by Liliana Cavani (“The Night Porter“) and starring John Malkovich, Ray Winstone and Dougray Scott. It’s a more straightforward thriller, but Wenders’ is a stranger and more mysterious film.

Also: Watching “The American Friend” on DVD the other night reminded me that perhaps many cinephiles today don’t know how lucky they are. It features a spectacular, expressionistic use of intense color, and it has never looked better than it does on DVD (in a dark room, on a big-screen HDTV). Those of us who first saw these movies in the ’70s generally saw dirty, scratchy 35mm repertory prints (if we were lucky) or X-generation 16mm nontheatrical prints struck from other prints that looked like old color xerox copies. A lot of Wenders and Fassbinder films were first seen this way. Even the worst DVDs are no sludgier than many of the nontheatrical prints some American distributors used to rent to schools and film societies at premium prices.

* We’ve glimpsed Miss Liberty’s counterpart in Paris at a crucial moment earlier in the film.