By Roger Ebert

On Aug. 31 I published a review of a movie titled “Delirious.” I gave it 3½ stars. I liked it a lot. Maybe you remember that it starred Steve Buscemi as Les, a mad-dog paparazzo, scorned by the world. He becomes the hero of a clueless street kid named Toby (Michael Pitt) who begs to hang around with him and learn the ropes. So Les moves Toby into a cupboard of his fleabag apartment and pontificates on the art of catching celebrities off-guard. Alison Lohman plays a Paris Hilton-type starlet who is their quarry. Also in the cast: Gina Gershon, Elvis Costello.

You have not seen this movie. You couldn’t have, unless you were one of the few customers who contributed to its depressing $200,000 total national gross. It got enthusiastic reviews from both trade papers, the New York Times, Salon, the New Yorker and so on, but then it disappeared.

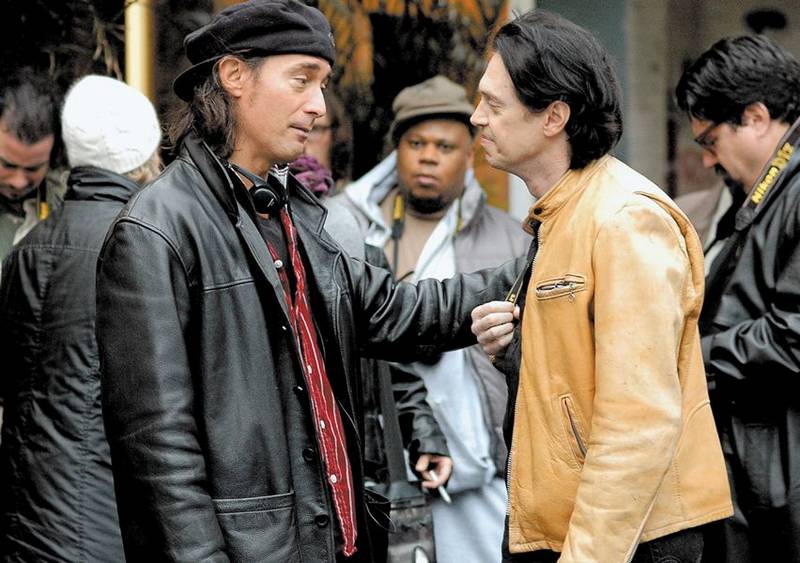

It was written and directed by a legend in the indie film world, Tom DiCillo, who has made other movies I’ve liked (“Living in Oblivion,” “Box of Moonlight,” “The Real Blonde“). Yet it opened in two theaters in New York and Los Angeles, was supported by pitiful near-zero advertising, went to one theater in each city after a week, had brief one-theater runs here and there (in Chicago, at the Music Box), and disappeared. It did have the distinction of inspiring a review by Ray Pride of New City Chicago that reads like ol’ Ray overdosed on Mean Pills. To criticize the great Buscemi for having skinny legs that look bad in black socks is over-reaching, I would say.

I’ve never met DiCillo, but after the disappointing release of his movie I got an e-mail from him.

“To give you some indication of how disoriented I feel at the moment,” he wrote, “I am getting no real, tangible feedback from anyone. And so I’m kind of struggling on my own to make sense of how a film I put my soul into, that Buscemi put his soul into, a film that generated such strong, positive reviews, had no life in the market.

“I’m not talking about gigantic box office success. I’m simply speaking of a modestly successful run that earned people their money back and, more productively, helped encourage other financiers and studios to invest in another one of my films. Of course I’m extremely proud of the film. Of course I feel a sense of victory in just getting it made. But for a filmmaker to survive there has to be some form of return.

“This is not intended to be a complaint or Whine Fest. I know this is a brutal business and I’m not asking for, nor expecting, special treatment, babying or sympathy from anyone. I’m just looking for some answers.”

In his blog (tomdicillo.com), DiCillo pulls no punches in describing the way his film was mistreated and manhandled. I think he may have a book in there somewhere. But my concern is that an entertaining film with a superb Buscemi performance has disappeared, and that it never had a chance. In his message DiCillo went on to employ colorful language about his nightmare, and then he presented me with a list of questions. I don’t have the answers, because there probably aren’t any, but, because they address a crisis in the indie film world, here goes:

Reviews work best in connection with a visible opening. When moviegoers have never seen an ad for a movie and it isn’t playing in their city, state or region of the nation, what difference do reviews make?

Apart from that, here’s a funny thing: Lots of moviegoers trust a critic less than a brainless ad promising them the sun, the moon and the stars. They have a certain reluctance to see a movie that might be good. Millions of teenage boys, in particular, flock to the stupid and the brutal, and have no interest in any film that involves words like “paparazzi.” (Millions of others are our hope for the future, of course, but opening weekends are driven by horror, superheroes and comic book and game adaptations, and depend on the fanboys.)

Because I enjoyed it from beginning to end, I wouldn’t call it unmarketable, but it isn’t a high-concept (i.e., low-concept) film, and it needs a chance to be discovered.

Let me give you an example. The second funniest film I’ve seen in the last 10 years is “The Castle” (1997), from Australia. When I showed it at my Overlooked Film Festival, the 1,600 people in the audience almost lost their lunch, they were laughing so hard. It grossed less than a million in North America. It didn’t have stars, it wasn’t about castles, and hardly anybody went. So it wasn’t “marketable.” Because I Iove movies, it cheers me up when people have a good time at one. This one was released by the old Miramax. “The test audience didn’t like it,” Harvey Weinstein told me, after he yanked it. OK, either (a) the test audience was wrong, or (b) it was the wrong test audience.

3. If a small film like “Delirious” is judged by its opening weekend gross for survival, what does that say about the state of U.S. independent film? In other words, if an independent film needs a big opening weekend to succeed, how does this make it different from a Hollywood film?

It says indies are being forced out by the Opening Weekend Syndrome. Indie films will rarely have big opening weekends because they don’t have the publicity machines to grind out press junkets, talk-show guest shots, celeb magazine profiles, big ad campaigns, and fast-food tie-ins. They need a chance to find an audience. “Chariots of Fire” (1981) opened in one theater, crept into two or three, tip-toed across the country, had great word of mouth, played for months, and won the Oscar. Today, it would have closed after that first theater. Here’s a hypothesis: Anyone reading this article is likely to enjoy a movie more if it doesn’t have free collectibles at McDonald’s.

Hard to say, because so many indie films are labors of love that their makers had to make. Consider Miranda July’s “Me and You and Everyone We Know” (2005), which had a $2 million budget and grossed less than $4 million. Not so great. When the lights went up at Sundance, Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly was across the aisle from me. “Whatd’ya think?” she asked me or I asked her, I can’t remember which. I remember the reply: “I think it’s the best film in the festival.” Other person: “Me, too.” How in the hell can a movie that delicate and magical not find a big audience when I know there are people starving for films like that?

Yes, barely. The irony is that indies are embraced at film festivals, which have almost become an alternative distribution channel. “Delirious,” for example, was invited by San Sebastian, Sundance, San Francisco, Seattle, Avignon, Munich and Karlovy Vary. All major festivals. But you didn’t make “Delirious” to sell tickets for festivals. I frankly think it’s time for festivals to give their entries a cut of the box office.

If there is room for hope, it’s that good actors are happy to appear in them because the indies are a repository of great roles. Halle Berry has starred in movies budgeted at millions, but won the Oscar for “Monster's Ball.” Robert De Niro top-lined millions of bucks, but won the Oscar for the low-budget “Raging Bull.” Charlize Theron could pull down $1 million-$2 million a picture or more, but won the Oscar for “Monster,” which cost lots less than a million. Actors know that beyond a certain budget level, mega-productions are less likely to contain great acting opportunities. What’s being marketed is the spectacle, not the performances.

I don’t know. Maybe DVDs and Netflix and Blockbuster on Demand and cable TV and pay-per-view and especially high-quality streaming on the Internet will rescue you and your fellow independents. I come from an innocent and hopeful time when we went to the Art Theater in Champaign-Urbana to see anything they were showing, because we knew it wouldn’t have Frankie Avalon in it, and they gave you a free cup of coffee, and we thought that was way cool. It was a movie by Cassavetes or Shirley Clarke? Or DiCillo or Sayles or Jarmusch? How did we get so lucky?