The movies are of course a time capsule, and I have rarely felt that more sharply than while watching the 25th anniversary edition of “Woodstock.” What other generation has so completely captured its youth on film, for better and worse, than the Woodstock Nation? Watching the film today, for someone like me who also saw it on the day it was premiered, inspires meditation as well as joy, dark thoughts as well as hopeful ones.

The making of the film was a happy accident. I remember meeting the director, Michael Wadleigh, in an editing room up in a loft in New York City, months before the movie was released. He talked about how he and his partner, producer Bob Maurice, threw together a production team at the last moment, and descended on the Woodstock site because they had a hunch it might be more than just another rock concert.

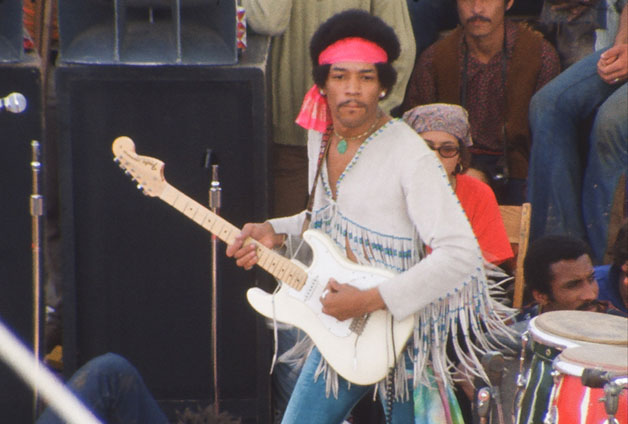

What they came away with was 120 miles of footage, which an editing team headed by Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese assembled into a three-hour film. The balance was perhaps 60 percent about the music and 40 percent about the event itself – about how 400,000 people were drawn to a farm in upstate New York, where the facilities could not remotely sustain or feed them, and where a thunderstorm soaked them, but where somehow they celebrated, as the film’s subtitle has it, “three days of peace and freedom.” This new “director’s cut,” which is playing at the Music Box and will be available on tape and laserdisc, adds an additional 45 minutes, including sets by Janis Joplin and Jefferson Airplane which were not in the original film. It also expands the film’s final performance, by Jimi Hendrix, which includes his pyrotechnic performance of “The Star Spangled Banner.” That performance was attacked by some at the time as a desecration of the national anthem. Hearing it again the other day, I found it the most stirring version of the song I have ever heard.

Hendrix tortured his electric guitar to create the sound of bombs bursting in air, as they were at that moment in Vietnam, and like a jazzman he improvised, working in bits of other songs (I’ve heard this version many times, but only on this hearing did I pick up 15 notes of “Taps“). As Hendrix plays, the camera shows the last act of Woodstock. Most of the 400,000 have gone home. A few forlorn wanderers walk barefoot across the muddy fields, trying to find shoes that will fit. Trash crews pick up the debris. The event is over. And then the editors slowly reverse the time flow, so that the field fills again, horizon to horizon, with a mass of humanity. It was then and probably still is the largest crowd ever gathered.

It is probable that Woodstock would not have been possible without Vietnam. They are two sides of the same coin: The grinning nun flashing a peace sign to the camera at the concert, and the war.

One of the heroes of the film is the Port-a-San man, in charge of servicing the portable toilets. After swabbing out a few units, he confides to the camera that he has a son out there in the crowd somewhere – “and another one in the DMZ, flying helicopters.” The concert, with its pot-smoking, its skinny-dipping, its warnings about “bad acid,” its famous shot of a couple disrobing and making love in a meadow, and Country Joe leading a singalong of “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” was in its own way a peace rally.

Without the war to polarize American society, these 400,000 people might not have felt so much in common. I remembered that time when strangers flashed the peace sign to each other, when costume and attitude created a feeling of camaraderie, when it was believed that music made a difference and could affect society. All of that is gone, gone, gone.

So are some of the performers, dead of drugs. Hendrix, of course, and Janis Joplin, who has always seemed weathered in my memory, but here seems touchingly young, because she did not grow older with the rest of us. Others were survivors: Roger Daltrey, Joan Baez, Grace Slick, who in the Airplane set looks like a fresh-faced college girl. Even Country Joe McDonald looks young here. It was all so long ago.

The structure of the documentary is roughly chronological.

We see the fields being prepared, the stage being built, the massive traffic jams forming. We see crowds trampling over the fences, and there is the moment when the event, conceived as a profit-making enterprise, is officially declared a “free concert.” (There is an amusing moment when the late Bill Graham, a concert promoter who always kept his eye on the gate, advises the organizers, facetiously I think, to fill ditches with flaming oil to keep the gate-crashers out.) “Woodstock” was made at a time before rock concerts were routinely filmed (although earlier documentaries about the Stones, Bob Dylan and the Newport Jazz Festival pointed the way). The stars were not performing for the camera. Richie Havens casually stops in the middle of a set to tune his guitar. Sha-Na-Na does a cornball double-time version of “At the Hop” and doesn’t care how it looks.

Joan Baez puts down her guitar and sings “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and nobody worries that it will slow down the show. Night follows day, day follows night, Hugh Romney of the Hog Farm announces “What we have in mind is breakfast in bed for 400,000 people.” Army helicopters drop food, blankets, medical supplies – and flowers.

Babies are born and no one is killed, and for a moment it seems that the spirit of Woodstock Nation could prevail.

Looking up my old review of the movie, I find that I began it with a quote from the Chicago Seven trial. Accused conspirator Abbie Hoffman is asked where he resides, and he replies, “Woodstock Nation.” His attorney asks him to explain to the judge and jury where that is. “It is a nation of alienated young people,” Hoffman says.

“We carry it around with us as a state of mind, in the same way the Sioux Indians carry the Sioux nation with them.” Yes, I thought, looking at the old clipping. And look what happened to the Sioux.