The fashion world and the film world co-mingle all the time. Designers become directors; models become actors. This is nothing new. And it makes sense if you stop and think about it. Both pursuits aim to set a mood, tell an artful story that transports you, whisk you away to a fantasy realm for a little while.

But not everyone can make that transition as successfully as the assured Tom Ford, for example, who has established himself a masterful, precise filmmaker with just two features: “A Single Man” and “Nocturnal Animals.” Hence, we have “Woodshock,” the debut from Kate and Laura Mulleavy, the sisters behind the Rodarte label. Previously, their best-known foray into film was the exquisite ballet costume work they did on Darren Aronofsky’s “Black Swan.” Now they’ve written, directed and (naturally) designed the clothes, but while “Woodshock” does indeed have a signature style, it’s in the service of a film that is stultifyingly dull.

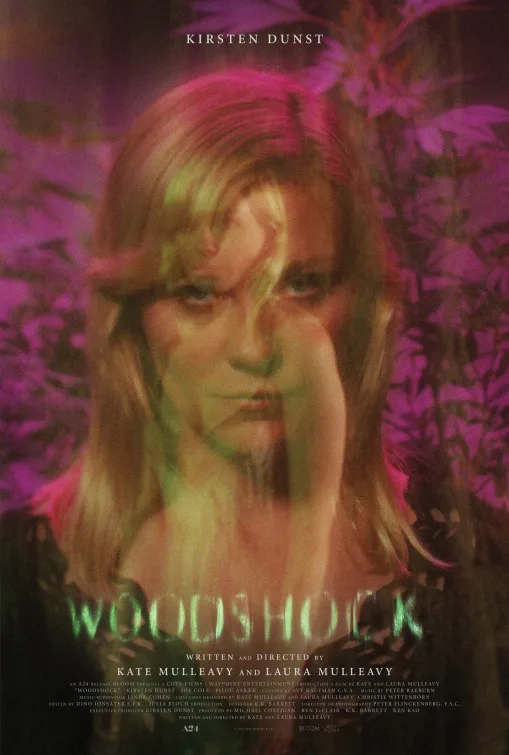

Medical marijuana is a constant throughout “Woodshock,” and unfortunately, it feels like the Mulleavys were trying to create a hazy, lazy vibe for their viewers, as well. The characters move as if slogging through molasses. The quiet, Northern California town where the movie takes place is blanketed in a perpetual fog. And as Kirsten Dunst’s Theresa grows increasingly isolated and confused, the Mulleavys crank up the hackneyed, experimental visual tricks to signify her inner state: double exposures, lens flares, flashing neon signs, stream-of-consciousness editing.

It’s all pseudo-significant, film-school twaddle, totally lacking in momentum and character development. An actress as resourceful and versatile as Dunst can only do so much when she’s given so little to work with.

Theresa’s descent into complete despair doesn’t look too different from her despondent state in the film’s opening scene, which deceives us into thinking that “Woodshock” might actually be compelling. We watch as she rolls a joint, which she’s laced with a few drops of mysterious liquid from a small, brown vial. Then she lights it and hands it to her mother (Susan Traylor), who’s lying in bed, suffering from some sort of terminal illness. A few puffs and tears later, the pain is gone for good.

From there, the entirety of “Woodshock” follows Theresa as she works through the anguish and eventual guilt of having helped mother commit suicide. Basically, this consists of her meandering in a perpetual funk, which often manifests itself in long, dreamlike walks through a stately redwood forest, usually in a nightgown. Sometimes, she sleeps atop the stumps of trees that have been cut down, hence the title … maybe? Surely, it’s all meant to be heavily symbolic, but the result is as profound as a Vogue magazine spread.

Various people try to get her to snap out of it, including her cold, impatient boyfriend, Nick (Joe Cole), who now lives with her in her mother’s house—a place that, like everything else in “Woodshock,” is mired in a studied, ‘70s aesthetic. With its wood paneling, vintage cars and trucks, conspicuous lack of modern technology and a carefully curated jukebox collection at the local watering hole, the movie might take place several decades ago, or it might just be wallowing in retro, hipster chic. Who knows?

Like all the relationships in “Woodshock,” the one between Theresa and Nick is barely fleshed out. But while he isn’t terribly supportive in her time of need, her flirty friend Keith (Pilou Asbaek), is too eager to keep her company—calling her all the time and inviting her out to bars and parties. Keith also happens to own the medical marijuana dispensary where Theresa works and, ostensibly, he’s the one who gave her the magical liquid that helped her put her mother out of her misery.

But in keeping with the movie’s relentlessly dour tone, even Keith is a bummer, although he’s supposed to be the town’s roguish, hard-drinking party boy. A subplot in which he tasks Theresa with helping other people cross over to the great beyond through his product is meant to be crucial to the story, but it never achieves its intended emotional punch.

And so when there is a climactic jolt of violent action, it comes out of nowhere, and it’s so shockingly inconsistent with everything that preceded it that you’re more likely to burst out laughing than gasp in horror. Then again, the dream—or the drug-induced hallucination, or whatever this is—can only last for so long.