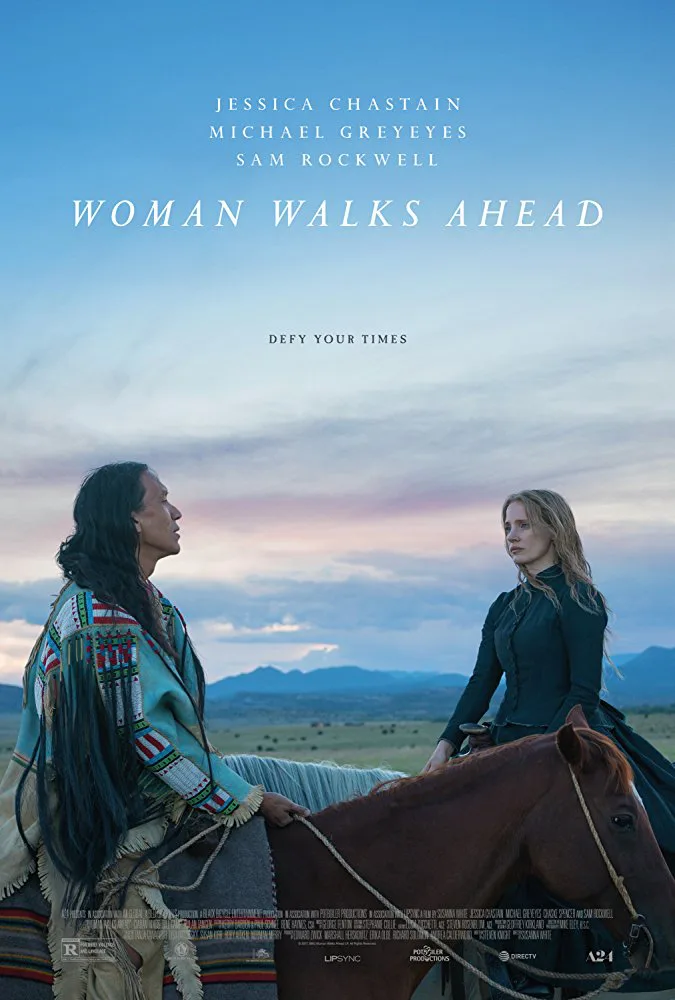

There is so much negativity, cruelty and ugliness in our world right now, it is hard to outright dismiss a well-intentioned stumble like “Woman Walks Ahead.” This truth-based odd-couple Western, about a late-19th century meeting of the minds between Brooklyn-based proto-feminist portrait painter Catherine Weldon and the legendary Lakota chief Sitting Bull, clumsily conflates our country’s racist genocide of Native Americans with the era’s marginalizing of women and their lack of rights.

But a few details are worth applauding. Topmost is the depiction of the breathtaking natural beauty of North Dakota’s plains (actually, New Mexico standing in) that practically cries out for gilded frames. Add to that a British female director, Susanna White (“Nanny McPhee and the Big Bang,” TV’s “Parade’s End”), who capably controls the reins for the most part and the fact that actual indigenous actors were recruited to fill the screen.

Alas, co-leads Jessica Chastain and Michael Greyeyes—both younger and more physically appealing than their real-life counterparts—do what they can to breathe some emotional fire into an underwhelming and often predictable script. Writer Steven Knight previously penned the devilishly nasty duo of “Dirty Pretty Things” and “Eastern Promises” and also inventively helmed “Locke,” Tom Hardy’s one-man show. But he takes too few risks here with this rather timid account of an unusual intimate relationship that apparently influenced the course of our frontier history. For a story that is not widely known, there is a distinct dearth of surprising twists. That includes Sam Rockwell, recent Oscar winner for his sneering racist and underhanded cop in “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” who shows up as—what else?—a snidely bigoted and deceitful military colonel here.

When “Woman Walks Ahead” premiered at the Toronto film fest last year, some found it guilty of being yet another white savior tale. After all, Weldon’s arrival at the Indian grounds is shown to coincide with the end of a three-month drought as raindrops begin to trickle down. But the film’s stars try their best to suggest that their characters are kindred spirits, equals as it were, as they both determinedly defy a white male hierarchy intent on passing a treaty that allows them to grab tribal land.

When we first glimpse Chastain’s headstrong widow, she is symbolically tossing her dead husband’s portrait off of a New York City bridge before embarking on a train journey to the Standing Rock reservation. Once there, she hopes to fulfill her dream of capturing the essence of the majestic Indian leader with her paint brush. At this point, I half-expected her to twirl around the dining car and sing “I Have Confidence” from “The Sound of Music.” Instead, her presence as a single woman in fancy dress, dragging a heavy suitcase and a passel of art supplies while walking on foot, pegs her not just an easy victim by an opportunistic thief, but also as a liberal Indian lover and possible spy.

She is told—nay, ordered—by Ciaran Hinds’ commanding officer, dismissively unsympathetic despite having an Indian wife, that she should hightail it back East pronto. Instead, Catherine insists on meeting Sitting Bull, and is taken by the chief’s nephew to the destitute settlement where he now resides. The once-mighty warrior is reduced to being a humble potato farmer now that buffalo herds have been depleted. He agrees to pose for the then princely sum of $1,000—which she knows will go a long way to support the deprived community that has welcomed her.

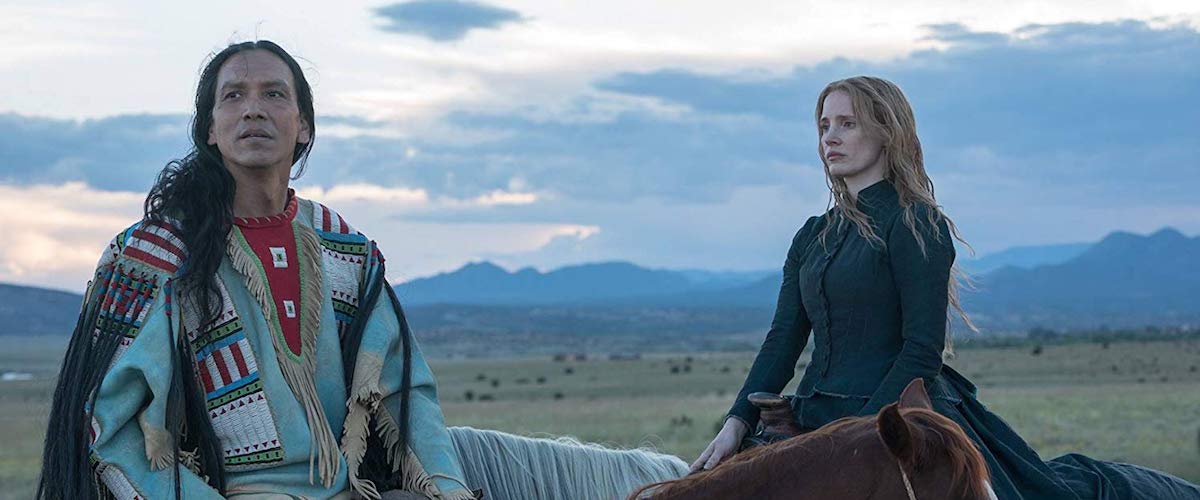

Much of “Woman Walks Ahead”—which is Sitting Bull’s nickname for his unlikely visitor, who has a habit of striding in front of the chief as they walk together—follows the gameplan of many a rom-com as two stubborn people who are in denial about their mutual attraction. The film comes perilously close to turning into a loincloth-ripper as the tall, well-built and impressively maned Greyeyes, a Canadian actor and trained ballet dancer, disrobes in a teepee and dons his traditional garb as Catherine averts her eyes. Later, as their bond grows stronger, they both change out of damp clothes while smoldering looks are shared. But White and Knight at least have the good taste to not let the pair to cross beyond that line.

Instead, the artist allows her subject to reclaim his pride and stand up for his people. And he takes this woman seriously after she puts herself at risk by being his friend and advocate for the natives. Interestingly enough, Greyeyes gives the more subtle, soulful and believable performance as he reflects upon the past and prepares for an uncertain future often predicted in his dreams. He also overcomes dialogue that sounds more like culture-clash catchphrases, such as, “Your society values people by how much you have. Ours, how much you give away.”

But Chastain’s big moment doesn’t do her any favors, as Catherine weeps while relating how, when she was eight years old, her father locked her in a stable with a horse, causing her to fear the beasts. “He decided I needed to be taught to obey, broken like a horse, because I wasn’t acting like a lady.” Her crime? Wiping her mouth on her sleeve. Of course, there eventually is a scene where she triumphantly conquers her trauma atop Rico, a white stallion who was given to Sitting Bull by Buffalo Bill. Unfortunately, what is supposed to be a vulnerable revelation devolves into Catherine declaring, “It’s darn hard being brave,” a statement that the chief knows all too well after surviving the Battle of Little Big Horn.

A tragic end is inevitable, one that would be more emotional if the lead-up to it dug deeper and allowed the characters to show their feelings more than tell. Unfortunately, “Woman Walks Ahead” is too often one step behind in making us care.