In the lyrical film “War Pony”—an evocative tale of recurrent tribulation and dogged community spirit—Native strivers and hustlers roam the brutal clime of the Pine Ridge Reservation in search of a life raft to another day. To understand the plight affecting those Oglala Lakota and Sicangu Lakota citizens of the Oglala Sioux Tribe and Rosebud Sioux Tribe, one must first be aware of the broken treaties that lead to their contemporary settlement and the tribal sovereignty that now governs these areas.

Up until “Reservation Dogs” and “Wild Indian,” Chris Eyre’s “Smoke Signals” was a notable exception as a mainstream work by Indigenous creatives. On the flip side, there are also innumerable examples of white folk exploiting Indigenous culture for either economic or artistic gain. With two white filmmakers helming “War Pony,” it would appear, at first blush, that another outsider’s conception of Indigenous history is in the cards.

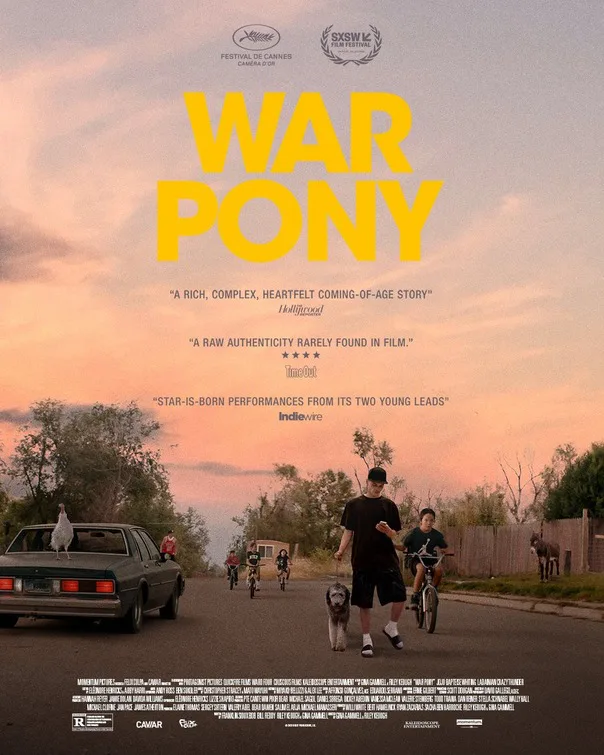

Co-directors Gina Gammell and Riley Keough want to avoid such perceptions. Their film is a collaborative effort that began while Riley was filming “American Honey.” There she met two extras, the eventual co-writers of “War Pony,” Bill Reddy and Franklin Sioux Bob, who shared their Rez stories. These conversations would eventually inspire the trio and Gammell to compose their feature. The fruits of their exchange bear an immersive, albeit deeply cliched, collision between magic and neorealism.

The electrifying first-time actor Jojo Bapteise Whiting stars as Bill, a 23-year-old swaggering striver with a baby momma, two young children, and zero career prospects. He pulls a few tricks and hustles when he learns his baby momma, presently in jail, needs $400 for bail. First, he buys a poodle from a shady character hoping to breed the dog for big money. Then he attempts to pawn his car and his PS4. But he makes his firmest bid toward upward mobility when he sees Tim (Sprague Hollander), marooned with his pickup truck at the side of a dirt road.

Though Tim is married, he often fools around with Indigenous women. He has one in his truck. He elicits an agreement for Bill: In return for taking the woman home, he’ll give Bill the $400 he needs and a job at Tim’s turkey farm. The opportunity is a hustle that Bill hopes will grant him stability.

Ladainian Crazy Thunder also stars as Matho, a troubled 12-year-old kid living with an abusive drug-dealing father whose life seems to be hitting all the worst potholes. Matho and Bill aren’t directly related, not on familial grounds, but they are direct foils. Their divergent arcs, occurring in two different spaces on the Rez, convey the beginning of a cycle and the result of one. As Matho shifts from temporary homes to squatting in derelict buildings, from taking beatings to dealing drugs, from one flawed parental figure to another, you get the sense these are all obstacles Bill must have hit long ago.

Sometimes the editing between their narratives can be sporadic, leaving the impression that you’re watching two movies rather than two intertwining stories. Toward the end of the film, their eventual meeting veers toward predictability, even if I did appreciate the quiet staging and the soothing balm it provides.

“War Pony” has a cathartic transcendence when it engages with the tight bonds that form the community. A prominent instance occurs during a funeral when a convoy of cars swerves in snake-like unison as the plains landscape stretches behind them. Another happens at the end when the filmmakers combine the images of buffalo (the animal magically springs from nowhere) and turkeys for an anarchistic redistribution of resources, a kind of retribution for the appropriation that continues today.

And yet these scenes are few and far between in a movie that solely prizes trauma. At this point, it’s become a cudgel to accuse a film of being a shallow endeavor because it litigates the stories of a people through its possible horrific reality. Some lives are inherently disturbing. And it can be superficial to ask for nice bows to be affixed to tragic stories, particularly if they’re drawing on real-life experiences. But it’s not just the inner-city milieu of “War Pony” that recalls some of the cliches common to Black gangster dramas of the 1990s. It’s also the film’s inability to convey an existence outside of unwed mothers, apathetic parents, and brutal socioeconomic disparity that leaves one wanting.

Maybe that’s just the reality of Reddy and Sioux Bob’s community and the plethora of first-time extras and actors drawn from the area. From an outsider’s perspective, however, as poetic and otherworldly as “War Pony” can be, the reality of its people never feels real.

Now playing in theaters.