An essential element of youth is movement. Where are we going? What are we doing when we get there? There’s an energy to the hazy days of those teenage years that’s hard to capture on film—a sense of constant motion toward an uncertain future. It’s often a push and pull between what we want to do and what we’re ready for, as phrased in the song that gives Andrea Arnold’s “American Honey” its name: “Steady as a preacher/Free as a weed/Couldn’t wait to get goin’/But wasn’t quite ready to leave.” This brilliant European filmmaker’s look at youth culture in the middle of America is full of exaggerated imagery of the heartland of the United States—men in cowboy hats grilling meat by a pool, oil fields blazing at night, a trucker listening to The Boss, an extravagant teenage girl’s birthday party—but its beating heart is in a story of youth. Reckless, fearless, joyous, always-moving youth.

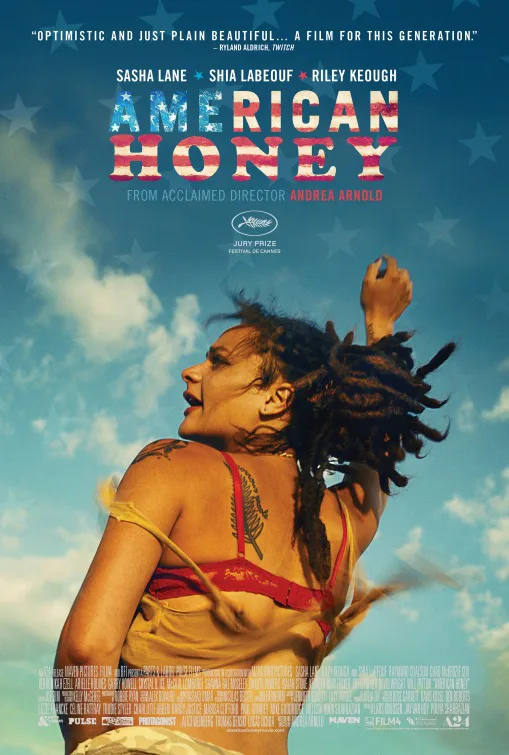

We meet Star (Sasha Lane) in a dumpster, looking for food. Quickly, she encounters a group of teenagers in a nearby mega-store and sees a chance to escape her unhappy home life. This group of smiling, jumping, dancing people, led by a flirtatious Jake (Shia LaBeouf), offer a way out for Star. Where they’re going to take her isn’t as important as the idea that they’re going somewhere, anywhere other than here. She learns that Jake is one of the leaders of the group, who travel the country selling magazines door to door. They really just do it enough to get food and lodging so they can keep doing it. They’re living day to day—partying, drinking, and singing their way across the country.

There are scant few traditional narrative elements to “American Honey.” There’s a bit of a villain in Riley Keough’s Krystal, the head of the magazine sales group who collects the cash and makes the assignments. And there’s an inevitable bit of a love story between Star and Jake, although it’s not a film anyone could call a romance. This is a not a film tied to plot. It often follows Star on adventures in the magazine sales trade, bringing her back to the group after random encounters across the country. And it is a film in which people convey emotion more through action and music than dialogue. When they’re happy, they dance—Arnold’s film is filled with pop songs, many of which are played in their entirety. When they sing along, they’re expressing the feeling of community they have created and that they need so badly. There’s a key moment near the end in which they all start slowly singing along to the same tune, almost one line at a time, until they are all together—multiple voices in common song.

Arnold shoots “American Honey” in her typical full-frame 1.33:1 style and it creates a visually fascinating aesthetic. One might think that it would hamper a film that could have so easily taken advantage of the widescreen vistas of the heart of the country, but it’s effective because it keeps us with our characters instead of visually wandering the landscape. It creates a privacy, a sense that we’re in the van with Star and the rest of the gang, joining them on this journey. And Arnold and cinematographer Robbie Ryan often shoot their teenagers from below, casting them larger than life against the blue sky.

Most of the supporting cast appear to be non-professionals who are improvising much of their dialogue, and they’re all natural and engaging—a testament to Arnold’s direction. The real find here is Lane, who makes her feature debut confidently, never feeling like she’s performing as much as living in the moment. LaBeouf has a ragged energy. We get the sense that he’s worked with a few Stars along the way, and while Arnold never explicitly gives him a detailed back story, one can sense that LaBeouf created one. Jake is confident but also needs the reassurance of people like Krystal and eventually Star as he probably senses his youthful days are coming to an end. It’s a rich, complex performance.

Ultimately, “American Honey” is about motion—a van of kids speeding down the freeway. Even when they stop at a motel to break, they use the chance to dance in the parking lot. We all remember those years when we couldn’t sit still—when hormones, ambition, and just the desire to see what was around the next corner kept us unsettled and needing to move. Andrea Arnold’s phenomenal work captures that propulsive teenage trait as well as anything in years. There is no yesterday, there is no today, there is only moving forward to tomorrow.