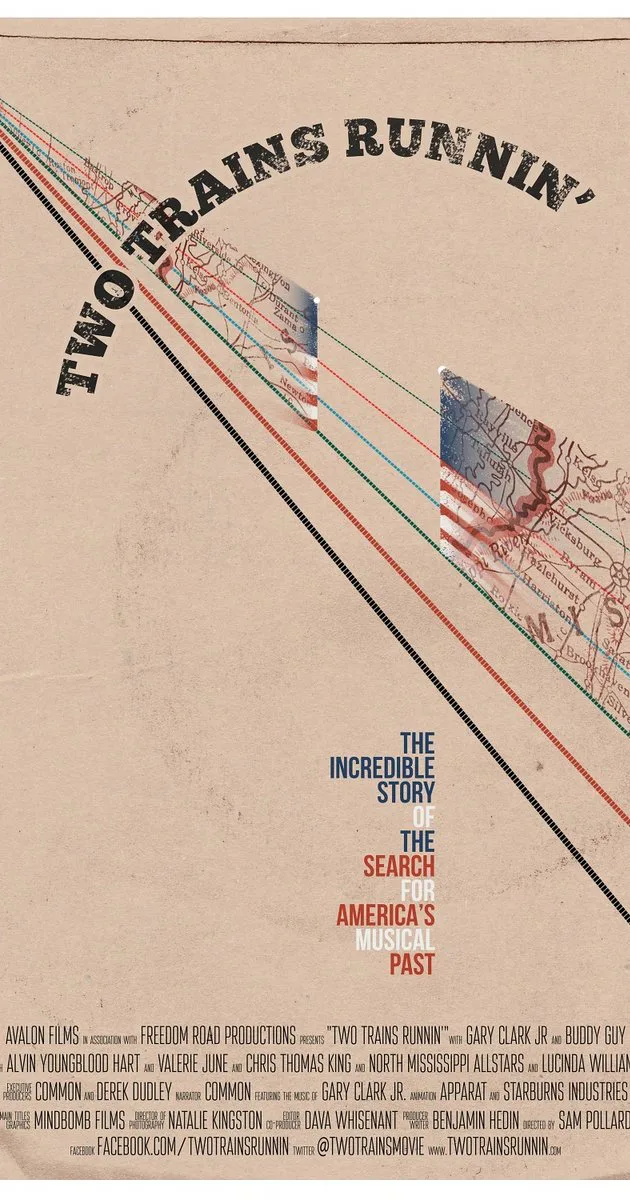

“Two Trains Runnin’” intermingles two completely unrelated non-fiction threads which converge in the state of Mississippi on June 21, 1964, One of them is triumphant, the other tragic. One is a well-known story, the other is a mystery whose outcome is not so well-known. Both sections feature idealistic, college-aged White men from the North whose quests could not have been more different: One group came to the segregated South looking for music while the other sought justice. Those Holy Grails are by no means equivalent, but director Samuel D. Pollard and his editor, Dava Whisenant, expertly weave these two threads into a thematically rich whole cloth. Hidden similarities emerge as “Two Trains Runnin’” rides towards its final destination.

“The US was a segregated nation at the time,” Phil Spiro tells us when we first hear his voice on the soundtrack. “But I was a prototypical White college kid at MIT, so it didn’t impact me very much.” This would explain why he, and two other people he recruited, would venture into Mississippi to search for an obscure blues musician who hadn’t recorded in 30 years. Unbeknownst to Spiro, Mississippi had a reputation as not only the most racist state in the Union, but also the least welcoming to outsiders of any hue. This was the year of the Freedom Summer. People were coming into the state to register Black voters, which was seen by Mississippians as the next wave of Northern Aggression. If you were a White out-of-towner, the residents would think you were planning to, in their words, “mess with our Nigras.” Spiro and company had no such agenda, but three Jewish guys in a Volkswagen with New York license plates were definitely going to raise the eyebrows under a Mississippi state trooper’s hat.

Spiro’s love of old Delta Blues records from the 1920’s and 1930’s was enough to get him to quit MIT and take a job coding for one of the world’s first computers. The gig allowed his nights to be free to pursue his musical obsession, Son House, a contemporary of Robert Johnson whose records were so powerful they gave Spiro goosebumps. Acting solely on a hot tip regarding House’s whereabouts that he received from a recently found blues musician named Booker White, Spiro went to Mississippi. He was accompanied by Dick Waterman, a journalist whose paper would publish the story if House was found, and Nick Perls, a guy who has a car, a tape recorder and a lot more money than Spiro anticipated. Perls is rich enough to live above a gallery of expensive art works.

While Waterman and Spiro have difficulty putting into words just what drew them to not only Son House’s music, but to the Delta blues music of the era, African-American author Greg Tate offers us a theory: “It spoke to another way of life that was more expressive, more erotic, more dangerous.” And yet, as many of the blues performers in “Two Trains Runnin’” point out, these Depression-era blues musicians were quite often singing about universal things like money and relationship problems. It only seemed exotic when viewed from within the bubble of privilege Spiro alludes to in his opening lines of dialogue.

At the same time Spiro’s Volkswagen was leaving New York City, John Fahey, another blues-loving musician, left California en route to find a musician named Skip James. James was reportedly even bigger and badder than Son House—he played guitar and piano and his songs were rough and dark. Fahey was the more experienced of the two musician hunters, having been to Mississippi previously on one of these missions. Fahey went to Bentonia, Mississippi, not too far from where Spiro will eventually wind up. “Two Trains Runnin’” documents these journeys with excellent animated sequences. They’re flawlessly integrated with the talking heads and the newsreel footage, and are just as compelling. One scene, involving a Black musician and a truckload of White field workers, is exceptionally tense despite it being rendered as a cartoon.

Spiro and Fahey discovered the whereabouts of their musicians on Mississippi on June 21, 1964, the same day Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, two White college students like Spiro, disappeared in Philadelphia, Mississippi, along with African-American fellow activist James Chaney. Their bodies were found six weeks later, causing nationwide outrage. Robert Moses and David Dennis, the organizers of the Mississippi Summer Project to register voters, appear onscreen to speak about this tragedy, and how it brought attention to the ugliness of the Jim Crow South. Pollard’s inclusion of Dennis choking up while discussing his lost charges is more powerful than the misguided and infuriating 1988 Alan Parker film, “Mississippi Burning,” which dramatized the same events.

Narrated by rapper Common, “Two Trains Runnin’” intercuts its stories with blues musicians singing and discussing Delta Blues songs. The musicians are young and old, Black and White, male and female, and all extremely talented. The songs become the glue that binds the movie’s seemingly disparate halves. When the stories converge, “Two Trains Runnin’” becomes a powerful meditation on the origins of an African-American musical genre and the painful reasons for its existence. The Freedom Summer exposed an otherwise cocooned America to why musicians like Son House and Skip James would sing the songs they did.

I’ve reviewed a lot of movies like this here at RogerEbert.com, and every time I wish I’ve could done so from a place where their stories existed as time capsules rather than reminders of how little has changed. Pollard brings last year’s Voting Rights Act changes into the film not only as a workable thematic connection but also as a warning. Someone in “Two Trains Runnin’” points out that in order for things to evolve, the people who aren’t affected by the problem need to be enlightened and enlisted for the cause. I felt a lot more optimistic about this message when I saw this film in October than when I saw it again very recently, but that doesn’t diminish its power. Pollard’s choice to end with a stirring a capella number by Son House still provided the uplift needed to fight another day.