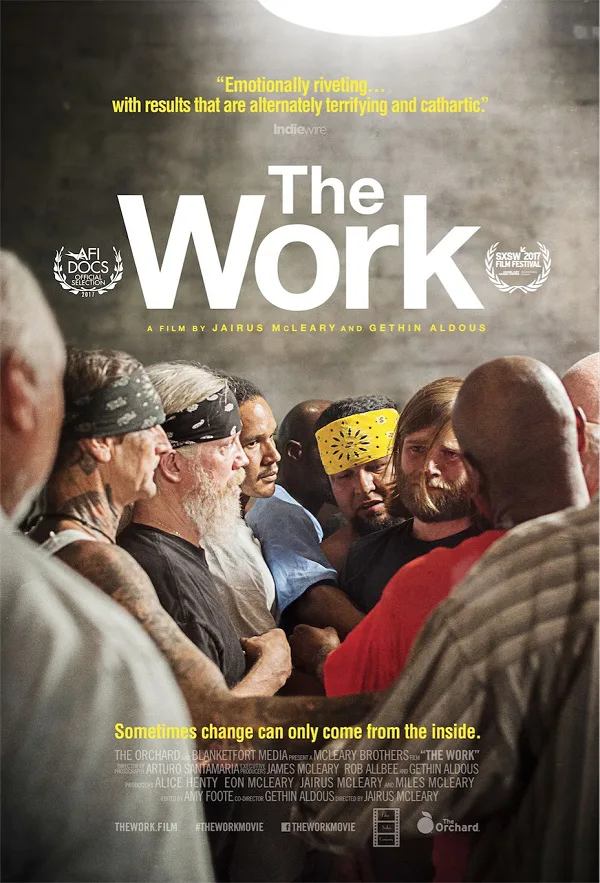

Jarius McLeary’s “The Work” has all the superficial trappings of a bland feel-good documentary that’s riddled with good intentions but fails to involve, formally or otherwise. A film about prison rehabilitation and the power of group therapy, “The Work” could easily have rested on the laurels of its admirable subject matter and preached instead of observed, constantly spoke instead of listened. By the 15-minute mark, however, it immediately becomes clear that McLeary and his co-director Gethin Aldous have no interest in infantilizing their audience. They are there simply to bear witness to hardened men, inside and outside of prison, breaking down the walls inside themselves. McLeary and Aldous’ only request is for its audience to follow them down that emotional chasm.

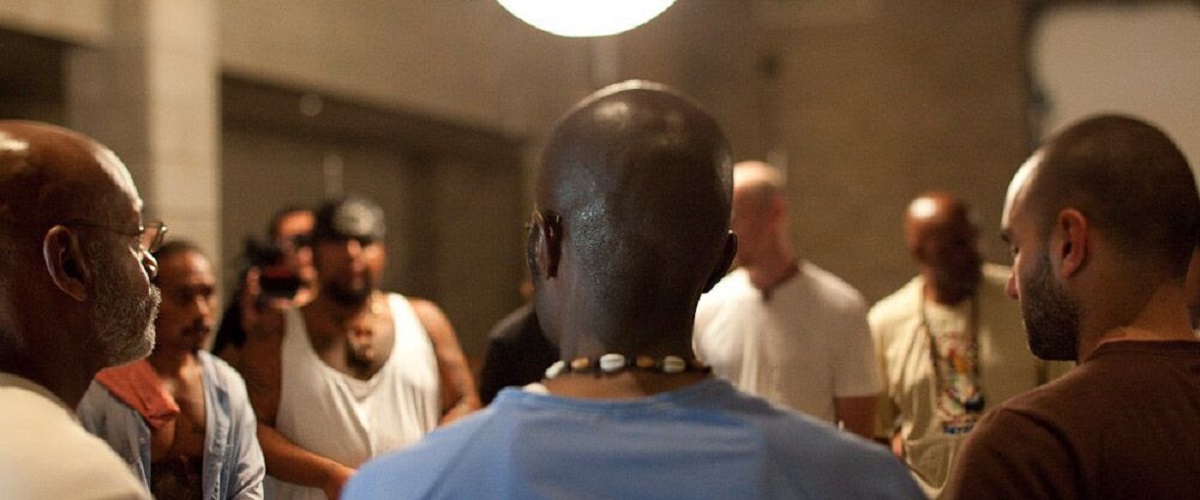

In Folsom State Prison, convicts meet weekly for intensive group therapy. Twice a year, they invite members of the public to join them for a four-day session. McLeary follows three citizens—Charles, a bartender and father of three; Chris, a twenty-something museum associate; and Brian, a teacher’s assistant—during their session as they share in and experience catharsis simply by agreeing to participate in such a vulnerable activity. All of them start from a hesitant, yet eager place, and all eventually expel some pain, even if it has to be dragged out of them by the inmates, who are still fighting their own demons.

The dramatic arcs of the subjects should be obvious to anyone who has even witnessed therapy from afar, but because McLeary never contrives any specific moment for the men to reach their own affecting emotional climaxes, they retain the ability to surprise and unsettle. In fact, the film’s first major sequence doesn’t involve any of the civilians, but rather Kiki, a man who has served 17 years for a murder/robbery conviction and doesn’t have the tools to properly mourn for the loss of his sister. McLeary fixes the camera on Kiki as a group leader pushes him to feel his sadness, marinating in the lengthy period when he tries to avoid the sorrow. Kiki eventually collapses in violent sobs, ejecting his hurt like a virus.

In “The Work,” McLeary doesn’t dabble in portraiture. He concisely communicates the pertinent truth about his subjects so they fill in three dimensions, but no more than that. Instead, he captures the singular moment of expulsion, when the floodgates open and there’s no hiding from the release. “The Work” operates on one tonal frequency by design; McLeary quickly goes up to 11 and never dials down. By returning to the same emotional well again and again, the film risks the possibility of hitting diminishing returns, especially because many of McLeary’s subjects share similar trauma. Indeed, the backstretch succumbs to some monotony. Yet, the honesty on display turns a potential bug into a feature.

McLeary appropriately doesn’t get in the way of his subjects or the setting. He captures his group members in close-up and allows their stories to resonate on their own. But his lack of explicit formal maneuvering doesn’t indicate an unsteady hand. He and his editor Amy Foote construct a series of moments that don’t add up to a neat narrative, yet suggest an open-ended journey, which is its own accomplishment. The aesthetic highlight of “The Work” involves microphones: As a group leader embraces an inmate, begging him not to give up on his life, he muffles both their mics, rendering their cries and words largely unintelligible. We watch this private, intimate moment for roughly a minute before the leader unclasps and the sound clarifies. It engenders the feeling of finding the first bit of light after climbing through a dark tunnel.

“The Work” never openly articulates any critique of masculinity, mostly because McLeary’s footage renders it unnecessary. By simply watching the participants talk about their feelings, sometimes in the vaguest of terms, McLeary illustrates how men build strong façades to conceal their pain from others and themselves. The film’s most powerful sequence involves Brian, who enters Folsom with a condescending edge. McLeary portrays him as a cocky professional who uses intellect and vocabulary as a weapon, someone who clearly treats others poorly likely without realizing it. His prisoner guides have him pegged right away; they know he’s a ticking time bomb that’s ready to explode, and they openly comment on how they see themselves in him. Sure enough, after a day and a half of judgment and false superiority towards his group members, he breaks, and the results are fairly shattering. “The Work” asserts that the collapse of emotional barriers feels like an exorcism, and that life’s true labor involves facing and contending with the blues inside us all. Prison blues doesn’t only belong to actual prisoners.