In an early scene of “The Wild Bunch,” the bunch rides into town past a crowd of children who are gathered with excitement around their game. They have trapped a scorpion and are watching it being tortured by ants. The eyes of Pike (William Holden), leader of the bunch, briefly meet the eyes of one of the children. Later in the film, a member of the bunch named Angel is captured by Mexican rebels and dragged around the town square behind one of the first automobiles anyone there has seen. Children run after the car, laughing. Near the end of the film, Pike is shot by a little boy who gets his hands on a gun.

The message here is not subtle, but then Sam Peckinpah was not a subtle director, preferring sweeping gestures to small points.

It is that the mantle of violence is passing from the old professionals like Pike and his bunch, who operate according to a code, into the hands of a new generation that learns to kill more impersonally, as a game, or with machines.

The movie takes place in 1913, on the eve of World War I.

“We gotta start thinking beyond our guns,” one of the bunch observes.

“Those days are closing fast.” And another, looking at the newfangled auto, says, “They’re gonna use them in the war, they say.” It is not a war that would have meaning within his intensely individual frame of reference; he knows loyalty to his bunch, and senses it is the end of his era.

This new version of “The Wild Bunch,” carefully restored to its original running time of 144 minutes, includes several scenes not widely seen since the movie had its world premiere in 1969. Most of them fill in details from the earlier life of Pike, including his guilt over betraying Thornton (Robert Ryan), who was once a member of the bunch but is now leading the posse of bounty hunters on their trail. Without these scenes, the movie seems more empty and existential, as if Pike and his men seek death after reaching the end of the trail. With them, Pike’s actions are more motivated: He feels unsure of himself and the role he plays.

I saw the original version at the world premiere in 1969, as part of a week-long boondoggle during which Warner Bros. screened five of its new films in the Bahamas for 450 critics and reporters.

It was party time, not the right venue for what became one of the most controversial films of its time – praised and condemned with equal vehemence, like “Pulp Fiction.” At a press conference the following morning, Holden and Peckinpah hid behind dark glasses and deep scowls. After a reporter from Reader’s Digest got up to attack them for making the film, I stood up in defense; I felt, then and now, that “The Wild Bunch” is one of the great defining moments of modern movies.

But no one saw the 144-minute version for many years. It was cut. Not because of violence (only quiet scenes were removed), but because it was too long to be shown three times in an evening. It was successful, but it was read as a celebration of compulsive, mindless violence; see the uncut version, and you get a better idea of what Peckinpah was driving at.

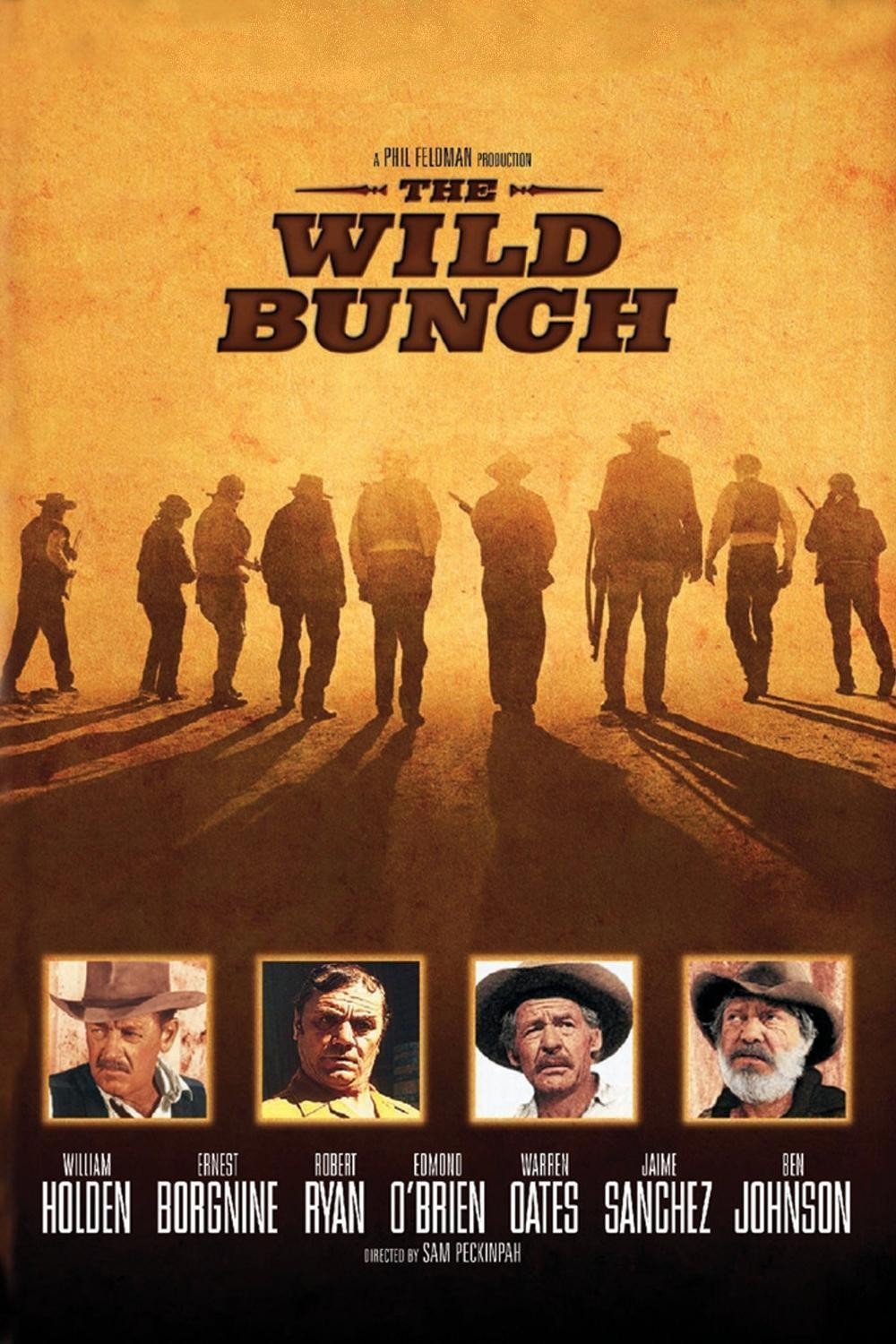

The movie is, first of all, about old and worn men. Holden and his fellow actors (Ernest Borgnine, Warren Oates, Edmund O’Brien, Ben Johnson and the wonderful Robert Ryan) look lined and bone-tired.

They have been making a living by crime for many years, and although Ryan is now hired by the law, it is only under threat that he will return to jail if he doesn’t capture the bunch. The men provided to him by a railroad mogul are shifty and unreliable; they don’t understand the code of the bunch.

And what is that code? It’s not very pleasant. It says that you stand by your friends and against the world, that you wrest a criminal living from the banks, the railroads and the other places where the money is, and that while you don’t shoot at civilians unnecessarily, it is best if they don’t get in the way.

The two great violent set-pieces in the movie involve a lot of civilians. One comes through a botched bank robbery at the beginning of the film, and the other comes at the end, where Pike looks at Angel’s body being dragged through the square, and says “God, I hate to see that,” and then later walks into a bordello and says, “Let’s go,” and everybody knows what he means, and they walk out and begin the suicidal showdown with the heavily armed rebels.

Lots of bystanders are killed in both sequences (one of the bunch picks a scrap from a woman’s dress off of his boot), but there is also cheap sentimentality, as when Pike gives gold to a prostitute with a child, before walking out to die.

In between the action sequences (which also include the famous scene where a bridge is bombed out from beneath mounted soldiers), there is a lot of time for the male bonding that Peckinpah celebrated in most of his films. His men shoot, screw, drink, and ride horses.

The quiet moments, with the firelight and the sad songs on the guitar and the sweet tender prostitutes, are like daydreams, with no standing in the bunch’s real world. This is not the kind of film that would likely be made today, but it represents its set of sad, empty values with real poetry.

The undercurrent of the action in “The Wild Bunch” is the sheer meaninglessness of it all. The first bank robbery nets only a bag of iron washers – “a dollar’s worth of steel holes.” The train robbery is well-planned, but the bunch cannot hold onto their takings. And at the end, after the bloodshed, when the Robert Ryan character sits for hours outside the gate of the compound, just thinking, there is the payoff: A new gang is getting together, to see what jobs might be left to do. With a wry smile he gets up to join them. There is nothing else to do, not for a man with his background.

The movie was photographed by Lucien Ballard, in dusty reds and golds and browns and shadows. The editing, by Lou Lombardo, uses slow motion to draw the violent scenes out into meditations on themselves.

Every actor was perfectly cast to play exactly what he could play; even the small roles need no explanation. Peckinpah possibly identified with the wild bunch. Like them, he was an obsolete, violent, hard-drinking misfit with his own code, and did not fit easily into the new world of automobiles, and Hollywood studios.

Seeing this restored version is like understanding the film at last. It is all there: Why Pike limps, what passed between Pike and Thornton in the old days, why Pike seems tortured by his thoughts and memories. Now, when we watch Ryan, as Thornton, sitting outside the gate and thinking, we know what he is remembering. It makes all the difference in the world.