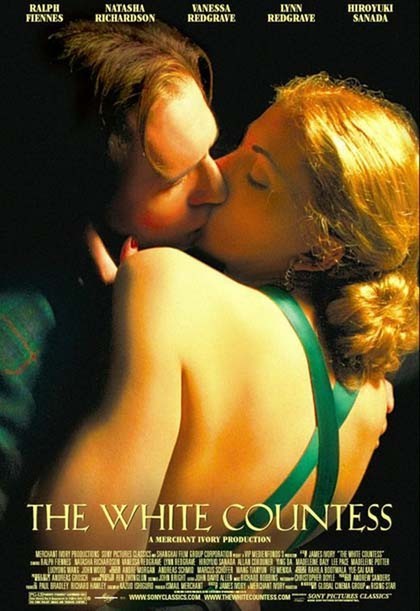

“The White Countess” is a film about a man who dreams of owning the perfect little bar, a place of elegance that finds the delicate balance, as he thinks a woman should, “between the erotic and the tragic.” Outside, it is Shanghai in 1936 and the world is late for its appointment with war. Inside the bar — well, inside, Mr. Jackson muses, “With a good team of bouncers, you could conduct the place like an orchestra.”

Mr. Jackson is a blind man who stands, or sometimes leans, at the center of the last of 28 films to be made together in this life by the director James Ivory and the producer Ismail Merchant. There were two more in pre-production when Merchant died in May 2005. They have been operating their own perfect little bar since 1963. Outside it is Hollywood, and the world is hurrying toward commerce and compromise. Inside their bar, cosmopolitan characters, elegant and tragic, have wandered out of the pages of good books; what many share is a personal style employed to conceal wounds, lusts and disappointments.

Todd Jackson (Ralph Fiennes) is a classic Merchant-Ivory character. He is an exile. He hoped for great things as a young man and now, disillusioned, hopes for smaller victories. He placed great trust in romance, now sees it as a hazard. He has taste. He needs money. He is comfortable with disreputable behavior, as long as it is conducted by the rules. Inside his world, friendships are possible that are otherwise forbidden.

Consider his friend Mr. Matsuda (Hiroyuki Sanada). Everyone knows the Japanese are going to invade China, and that Mr. Matsuda is their Shanghai advance man. Mr. Matsuda knows Mr. Jackson was once considered “the last hope of the League of Nations.” Mr. Jackson knows that Mr. Matsuda “would like to visit the bar of his dreams.”

What would this ideal bar be like? In another bar, which is not the right kind of bar, Mr. Jackson overhears a conversation involving the Countess Sofia Belinsky (Natasha Richardson), once Russian royalty, now supporting her exiled family by working as a taxi dancer. Everyone knows that to make ends meet, taxi dancers must sometimes “fall in love” with their clients. Sofia’s Russian family lives on her earnings while insulting her as a whore. Sofia’s little daughter Katya (Madeleine Daly) doesn’t know what a whore is, but defends her mother against her fierce grandmother and aunt (Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave): “If mama didn’t go out to work, then you would have to.” Quite so, and at wholesale.

One night, Sofia sees a situation developing in the shabby little bar where Jackson drinks, and quietly speaks to the blind man. She warns him he is about to be mugged and advises him to behave as her client. That will get him home unharmed. She wants no payment for this favor. “You’re perfect,” Jackson tells her. “You’re what I need.” She will be the hostess in his perfect little bar, talk with the customers, dance with them, decidedly not sleep with them.

The bar, when he wins the money to open it, is called the White Countess, and yes, in its way it is perfect. The jazz is good, the clientele is select, and Jackson has the right bouncers. The rest of the movie will involve the approaching collision between this perfect little world and the cataclysm of war.

Merchant and Ivory have never been much concerned with conventional melodrama, excitement and cheap thrills. Often working with the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, they have adapted works by such authors as Henry James (The Golden Bowl), E.M. Forster (Howard’s End, A Room With a View), and Kazuo Ishiguro (Remains of the Day); Ishiguro wrote this original screenplay. They have catered for a literate minority. If you have read this far, they have catered for you. In the perfect bar, you are likely to meet someone with every taste — even good taste.

Fiennes and Richardson make this film work with the quiet strangeness of their performances; if they insist on their eccentricities, it’s because they’ve paid them off and own them outright. Fiennes’ Jackson seems a little shaky for a man long accustomed to being blind, but not if he is also long accustomed to being a little drunk. Richardson’s Sofia seems a little too cultivated for a prostitute, and we are reminded of Marlene Dietrich’s great line, said by a character who lived in the same time and place: “It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.” But Sofia was raised as a countess and can hardly shed her elegance when she abandons her morals. These two fallen and needy people are reminded by each other of better times.

What we do is sit and watch them try to live up to their standards in a world that simply doesn’t care. I saw my first Merchant and Ivory film, “Shakespeare Wallah,” in 1965, so for 40 years, I have been watching them living up to their own standards when the world didn’t care and, lately, even when it did. Sometimes they have made great films, sometimes flawed ones, even bad ones, but never shabby or unworthy ones.

Here is one that is good to better, poignant, patient, moving. In the closing scenes, the movie loses its way as Jackson, Sofia and everybody else gets caught up in the chaos of the Japanese invasion, and melodrama is forced upon these reclusive souls. But no matter. No perfect little place lasts forever. The more perfect it is, the more word gets around and the wrong people blunder in and start fights.