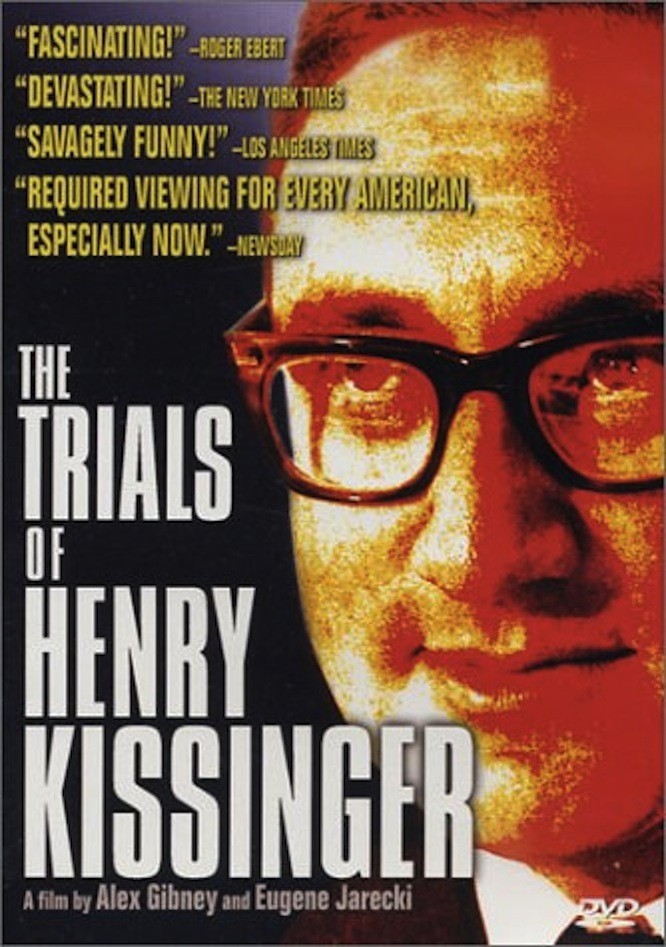

“The Trials of Henry Kissinger,” directed by Eugene Jarecki and based on the Hitchens’ 2001 book The Trial of Henry Kissinger, plays like a brief for a war crimes trial against the former secretary of state. It also plays like a roast, with easy jibes about his appetite for dating starlets and his avid careerism (at one point, we learn, he assured friends he would be the White House foreign policy advisor no matter whether Nixon or Humphrey was elected). The movie is not above cheap shots, as when it sets sequences to music.

The film’s technique is partisan. It provides Kissinger’s critics, including Hitchens, William Shawcross and Seymour Hersh, with ample time to spell out their charges against Kissinger (samples: he lied to Congress about the bombing of Cambodia, and lengthened the war in Vietnam by sending a secret message to the North Vietnamese that they’d get a better deal if they waited until Nixon was in office). Then Kissinger’s defenders are seen and heard, but hardly given equal time. It feels somehow as if the filmmakers have chosen just the words they want, and the context be damned; sophisticated media-watchers will note the editing tricks and suspect the film’s motives.

That was also a charge against Hitchens’ book: That he was such a rabid hater of Kissinger that he overstated his case, convicting Kissinger of what he suspected as well as what he could prove. More balanced criticisms of Kissinger were drowned out in the resulting controversy, and Hitchens, an easy target, drew attention away from harder targets that might have been less easily answered.

The film is nevertheless fascinating to watch as a portrait of political celebrity and ego. “Power is the greatest aphrodisiac,” Kissinger famously said, and he famously proved the truth of that epigram. In the years before his marriage he was seen with a parade of babes on his arm, including Jill St. John, Candice Bergen, Samantha Eggar, Shirley MacLaine, Marlo Thomas and, yes, Zsa Zsa Gabor. He dined out often and well in New York, Washington and world capitals, and his outgoing social life was in distinct contrast with the buttoned-down style of his boss, Nixon.

The movie shows him as a man lustful not so much for sex as for the appearance of conquest (many of his dates were at pains to report they were deposited chastely back home at the end of the evening). He liked the limelight, the power, the access, and he successfully tended the legend that he was indispensable to American foreign policy–so much so that he got credit for some of Nixon’s initiatives, such as the opening to China.

He meanwhile exercised great power, not always with discretion if the film is to be believed. There is an agonizing sound bite in which he regretfully observes that there is not always a clear choice between good and evil. Sometimes indeed evil must be done to bring about the greater good. All very well, but if the people of Chile elect a government we don’t like, does that give us the right to overthrow it? And even if it does, does that make the man who thought so a wise choice to investigate our current intelligence about terrorism?