In your average movie, helicopter shots are just for decoration. The camera soars over a breathtaking landscape or cityscape to show off the scenery and the production budget. These glorified establishing shots make the scale and the scope of the movie appear to be more expansive, even if they really aren’t.

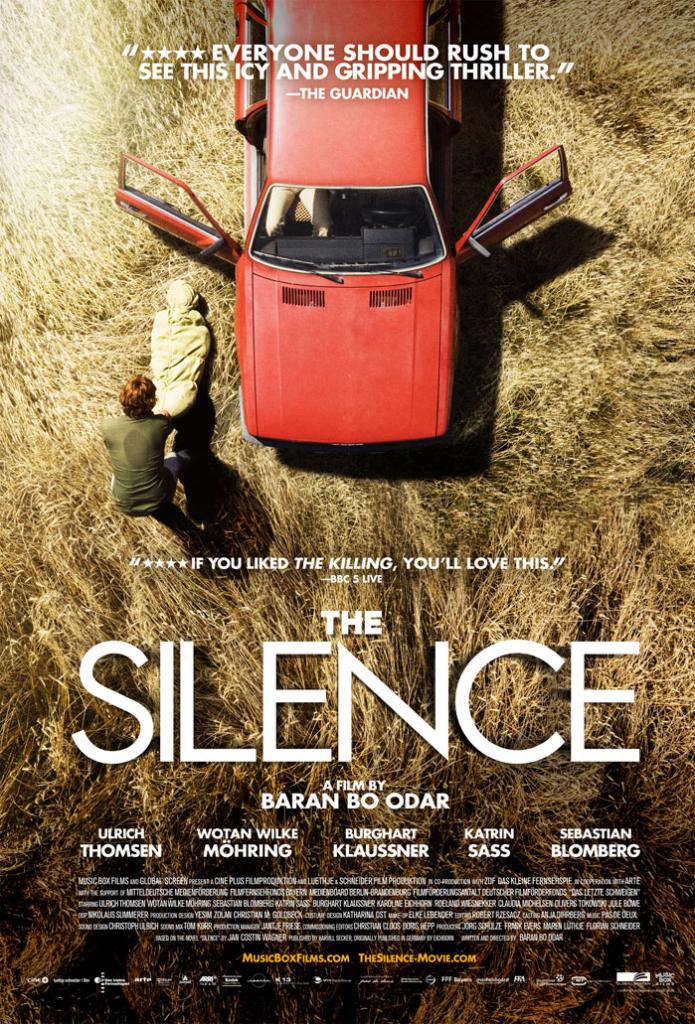

In Baran bo Odar’s first-rate thriller “The Silence,” the aerial panoramic images, which survey undeniably gorgeous slices of Bavarian countryside, express so much more. This is a movie about the gaps between two points in time and space — the murders of two young girls in the same spot, 23 years apart — and the invisible connections the deaths forge between people: Peer (Ulrich Thomsen), the maintenance worker who rapes and kills Pia (Helene Doppler); Timo (Wotan Wilke Mohring), his passive accomplice; Elena (Katrin Sass), Pia’s mother, who still takes flowers to the memorial on the bucolic spot where her daughter died; Krischan Mittich (Burghart Klaussner), the retired police detective haunted by his inability to solve Pia’s homicide; the Weghamms (Roeland Wiesnekker and Karoline Eichhorn), whose daughter, Sinikka (Anna Lena Klenke), becomes the second victim; Matthias Grimmer (Oliver Stokowski), the lead investigative officer on the new case who believes it’s merely a copycat killing, and his partner, David Jahn (Sebastian Blomberg), a damaged soul mourning the recent loss of his wife to cancer, who detects more personal links between the crimes.

The overhead images from helicopters and cranes are integral to the telling of the story, but also essential to tracking its reverberations. The twin killings in “The Silence” aren’t just crimes against individuals; they’re crimes against the natural order. Sometimes the aerial views are simply date-stamped chapter markers, dividing the narrative into discrete blocks of time; sometimes the camera rises as if tracing a silent howl of grief across the temporal and spatial landscape; sometimes they feel like the manifestations of an objective moral intelligence — not a “God’s-eye-view,” exactly, but a kind of cosmic perspective tracing the marks human beings make upon the Earth, literally and figuratively.

The film begins on a sizzling day in July, 1986. The camera closes in on two brown exterior doors in an anonymous apartment complex. Behind one of them, two men sit in semi-darkness, watching a grimy 16mm amateur bondage movie. A fan buzzes in the corner and an amber sliver of afternoon sunlight is exposed under the blinds. When the film runs out, the two men silently exit the building, walk to the garage and get into a car. They act with solemn determination, having apparently reached some sort of unspoken agreement about where they’re going and what they plan to do. The camera watches them — and the heedless everyday life all around them — from directly overhead. Until their vehicle comes up on a girl riding her bike beside the road, the view shifts to ground-level; in a chilling moment, she veers off the highway and down a perpendicular dirt road, riding directly away from the camera. The car passes by and, seconds later, backs into the frame and turns down the side road after her.

In the last decade or so, the northern Europeans have surpassed the Americans in the making of deeply unsettling thrillers that are gripping to watch and stay with you afterward — from the “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” (2010) trilogy to “The Bridge” (“Bron/Broen”) on television. American thrillers tend to be polished but stay focused on the superficial; they’re mainly about action, about interchangeable people and machines doing things. They leave out the juicy stuff that’s harder to convey — like who the people are, how they feel, what motivates them (beyond the formulaic contrivances necessary to the plot), and the physical and psychological details of the worlds in which they live. But this is what immerses you in a movie, not the simple mechanics of plot and action.

The obvious comparison here (girl murdered in the countryside of a Scandinavian nation; two flawed detectives investigate; grief-stricken parents) is “The Killing.” But that was a popular Danish TV series (later, a not-that-popular American one on AMC), and “The Silence” is a German film. This isn’t exactly a whodunit; we know the killer (of the first victim, anyway) from the start. We’re witnesses to her brutal death, obscured by stalks of wheat in the vast field where her life ends. The mysteries here are larger, deeper, more ineffable than the purely practical concerns of crime-solving: motive, means and opportunity.

What’s exceptional about “The Silence” is its style — the kinds of textures and colors that create memorable moments like those above. At times I was reminded of the symphony of grief reverberating through Twin Peaks after the discovery of Laura Palmer’s body in the pilot of David Lynch’s landmark series; the maddening, unresolved ambiguities of Bong Joon-Ho’s “Memories of Murder,” and David Fincher’s “Zodiac,” another film in which certain answers remain known and unknown at the same time. “The Silence” is the not-knowing.