“The November Man” is a strange and frustrating movie. It seems to want to be a James Bond or Jason Bourne picture: the kind of film in which car chases are tracked by satellites and drones, assassins cut down bushels of henchmen while barely batting an eye, and good and bad guys alike seem to just magically appear, a la Christopher Nolan superheroes, wherever the plot needs to them to be. At the same time, it wants to be a John Le Carre-type espionage drama, set in a version of reality and mixing allusions to real-world geopolitical traumas (including Russian-Chechnyan conflict and CIA black ops) into the heroes’ derring-do. The movie’s snarling, R-rated-tough-guy worldview—which includes graphic shootings, knifings, rapes, and sexist insults—sits uncomfortably with the movie’s desire to be a late-summer thrill ride. “The November Man” wants to be taken seriously, except when it doesn’t. This creates viewer whiplash. The movie is confused and often untrustworthy.

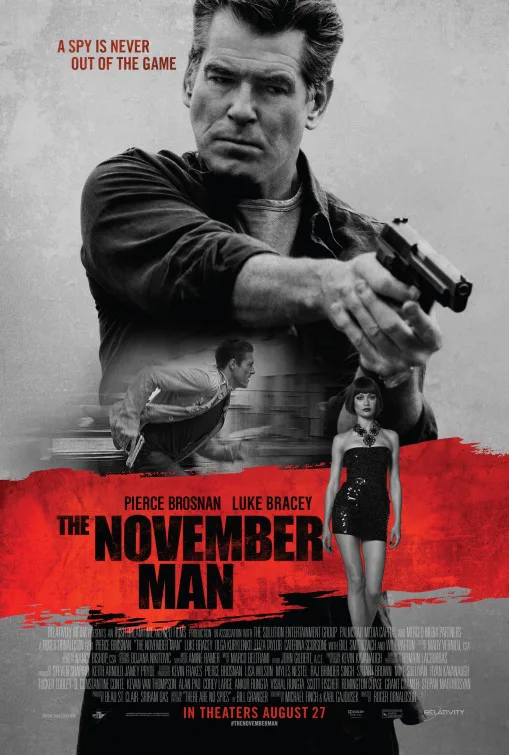

The movie opens with a brief flash-forward. Government assassin Peter Devereaux (Pierce Brosnan) blasts his trainee, David Mason (Luke Bracey), for disobeying orders in an operation that was supposed to thwart an assassination but ended up causing a child’s death. Five years later, David is ordered to kill a former Russian double-agent named Natalia (played by Mediha Musilovic) who broke into the office of the soon-to-be-elected president, Arkady Federov (Lazar Ristovski). Why? Without giving too much away, let’s just say that the CIA is up to no good, as is so often the case in movies and life, and that a self-interested power broker inside the agency wants to prevent the information that Natalia stole from getting out and embarrassing the agency. Unfortunately for whoever did this, Devereaux has a deep bond with Natalia. He embarks on a mission of revenge that also requires him to find a young woman named Alice Fournier (Olga Kurylenko) and prevent her from being killed by his former student David or by Russian agents (including Amila Terzimehic’s Alexa, a leggy mute whose stare could burn holes in concrete). Meanwhile, David tries to thwart or kill his old mentor—as the film itself jokes, he has daddy issues—while grappling with the suspicion that his lethal proficiency and loyalty are being abused for selfish purposes, in an off-the-books CIA operation whose outlines he can’t discern.

Nobody in the cast makes much of an impression except for the old pro character actors and Brosnan, who is perfectly cast as Devereaux. Handsome and lean but grey and haggard, he has twenty years’ worth of experience playing these sorts of men, starting with his version of James Bond, a colder, more self-loathing version of Ian Fleming’s super spy than fans were used to seeing. “I might as well ask you if all those vodka martinis ever silence the screams of all the men you’ve killed, or if you find forgiveness in the arms of all those willing women for all the dead ones you failed to protect,” another agent asked in “Goldeneye.”

“The November Man” is based on the seventh in a long-running series of novels about Devereaux by Bill Granger, but there are times when it seems to be a direct answer to that question, which Brosnan’s Bond answered with a knowing, faintly sad look. Devereaux is a highly functioning alcoholic who downs hard liquor the way other people drink water, and he admits to Alice that he has no life to speak of; he’s just a warm-blooded cipher living as far off the grid as he can, and trying to keep his personal relationships secret from the global espionage community so that they cannot be used against him. At one point Devereaux, who apparently quit the CIA out of slow-building revulsion, lectures his former pupil on the need for moral clarity, telling him that you can be a man or a killer of men, “but not both, because one will eventually extinguish the other.”

This is all intriguingly regretful and angry stuff. It’s not at all the sort of thing you normally encounter in the sorts of films where people beat each other senseless in basements and make spectacular kill-shots while sailing through the air unloading handguns. Donaldson, who directed Brosnan in “Dante's Peak,” is an unheralded master of down-and-dirty violence. The film’s most brutal moments have a sting that has largely disappeared from Hollywood movies. When people get shot or stabbed or hit in the face with a blunt object, the audience gasps as if it happened in front of them on the street. That sort of visceral intensity isn’t easy to conjure for viewers who think they’ve seen everything.

But it’s all in the service of an ultimately retrograde, cartoonishly macho vision of lone heroes doing what lone heroes do, so it’s hard to accept as anything other than a means of dressing up Bourne-style mayhem with a world weariness that the Bourne franchise did with more conviction. Movies about assassins and gunfighters and other killers who come out of retirement for one last mission often try and fail to solve this insincerity problem. The characters pay lip service to the notion that being a paid killer rots the soul—which is surely true—but nobody who bought a ticket wants to see them practice nonviolent resistance and play “Kumbaya” on a ukelele. “The November Man” knows this on some level, but it still genuflects in the direction of LeCarre, like a sneaky delinquent impersonating a scholar. It doesn’t actually regret violence, but there are moments when it seems to regret having to pretend to regret it. An old-school, Schwarzenegger-style bloodbath would’ve been more honest.

“The November Man” also fails to earn the power it summons whenever it shows us scenes of people threatened with torture, or bloodily maimed, or raped. At first you may think it’s a movie set in a sexist world, but soon enough you figure out that the film itself is sexist. When David’s superior officer (Bill Smitrovich) barks slurs at a female subordinate, at one point addressing her as “tits,” the moments are treated as tension breaking laugh lines. A sexually abused character seeks revenge by trying to seduce her abuser, and Donaldson’s camera caresses the lines of her cocktail dress, adopting the POV of her target’s lustful guards. A sweet innocent becomes collateral damage and suffers mightily; the film takes the character’s fear and physical pain seriously for a scene or two, whereupon that character vanishes from the story and is never seen or heard from again. The movie fails to develop the most important people in Devereaux’s life as characters, even obliquely, until the movie needs to terrorize or kill them to jack up suspense and sympathy. Despite occasional humanizing moments, including a shot which confirms that Kurylenko can actually play piano, the movie treats everyone as cannon fodder. Sam Peckinpah, this ain’t.