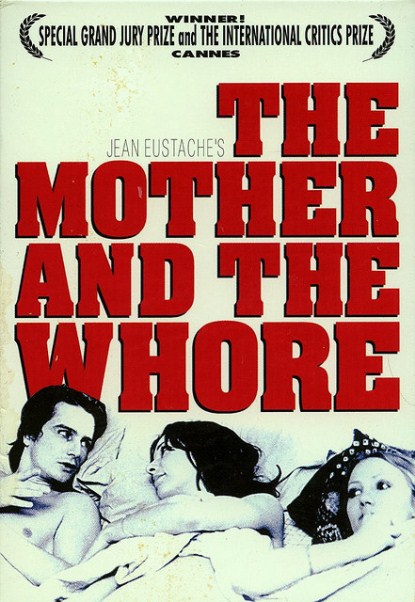

When Jean Eustache’s “The Mother and the Whore” was released in 1973, young audiences all over the world embraced its layabout hero and his endless conversations with the woman he lived with, the woman he was dating, the woman who rejected him and various other women encountered in the cafes of Paris. The character was played by Jean-Pierre Leaud, star of “The 400 Blows” and two other autobiographical films by Francois Truffaut. In 1977, Truffaut made “The Man Who Loved Women.” This one could have been titled “The Man Who Loved to Hear Himself Talk.” At 3 1/2 hours, the film is long, but its essence is to be long: Make it any shorter and it would have a plot and an outcome, when in fact Eustache simply wants to record an existence. Alexandre (Leaud), his hero, lives with Marie (Bernadette Lafont), a boutique owner who apparently supports him; one would say he was between jobs if there were any sense that he’d ever had one. He meets a blind date named Veronika (Francoise Lebrun) in a cafe and subjects her to a great many of his thoughts and would-be thoughts. (Much of Lebrun’s screen time consists of closeups of her listening.) In the middle of his monologues, Alexandre has a way of letting his eyes follow the progress of other women through his field of view.

Alexandre is smart enough, but not a great intellect. His favorite area of study is himself, but there he hasn’t made much headway. He chatters about the cinema and about life, sometimes confusing them (“films tell you how to live, how to make a kid”). He wears a dark coat and a very long scarf, knotted around his neck and sweeping to his knees; his best friend dresses the same way. He spends his days in cafes, holding (but not reading) Proust. “Look there’s Sartre–the drunk,” he says one day in Cafe Flore, and Eustache supplies a quick shot of several people at a table, one of whom may or may not be Sartre. Alexandre talks about Sartre staggering out after his long intellectual chats in the cafe, and speculates that the great man’s philosophy may be alcoholic musings.

The first time I saw “The Mother and the Whore,” I thought it was about Alexandre. After a viewing of the newly restored 35-mm. print being released for the movie’s 25th anniversary, I think it is just as much about the women, and about the way that women can let a man talk endlessly about himself while they regard him like a specimen of aberrant behavior. Women keep a man like Alexandre around, I suspect, out of curiosity about what new idiocy he will next exhibit.

Of course Alexandre is cheating–on Marie, with whom he lives, and on Veronica, whom he says he loves. Part of his style is to play with relationships, just to see what happens. The two women find out about each other, and eventually meet. There are some fireworks, but not as many as you might expect, maybe because neither one would be that devastated at losing Alexandre. Veronika, a nurse from Poland, is at least frank about herself: She sleeps around because she likes sex. She has a passionate monologue about her sexual needs and her resentment that women aren’t supposed to admit their feelings. Whether Alexandre has sex with Marie is a good question; I suppose the answer is yes, but you can’t be sure. She represents, of course, the mother, and Veronika thinks of herself as a whore; Alexandre has positioned himself in the cross hairs of the classic Freudian dilemma.

Jean-Pierre Leaud’s best performance was his first, as the fierce young 13-year-old who roamed Paris in “The 400 Blows,” idolizing Balzac and escaping into books and trouble as a way of dealing with his parents’ unhappy marriage. In a way, most of his adult performances are simply that boy, grown up. Here he smokes and talks incessantly, and wanders Paris like a puppet controlled by his libido. It’s amusing the way he performs for the women; there’s one shot in particular, where he takes a drink so theatrically it could be posing for a photo titled “I Take a Drink.” The genuine drama in the movie centers on Veronika, who more or less knows they are only playing at love while out of the sight of Marie. We learn a lot about her life–her room in the hospital, her schedule, her low self-esteem. When she does talk, it is from brave, unadulterated self-knowledge.

“The Mother and the Whore” made an enormous impact when it was released. It still works a quarter-century later because it was so focused on its subjects, and lacking in pretension. It is rigorously observant, the portrait of an immature man and two women who humor him for a while, paying the price that entails. Eustache committed suicide at 43, in 1981, after making about a dozen films, of which this is by far the best known. He said his film was intended as “the description of a normal course of events without the shortcuts of dramatization,” and described Alexander as a collector of “rare moments” that occupy his otherwise idle time. As a record of a kind of everyday Parisian life, the film is superb. We think of the cafes of Paris as hotbeds of fiery philosophical debate, but more often, I imagine, they are just like this: people talking, flirting, posing, drinking, smoking, telling the truth and lying, while waiting to see if real life will ever begin.