At Illinois we used to call it the “union crowd,” but whatever you call it, every campus has one: An ennui-laden group of students, mostly graduate students, who sit endlessly with each other in the student union or a nearby congenial bar, and who are addicted to coffee, cigarettes, leafing aimlessly through the paper, making desultory stabs at their current serious reading, and, in general, awaiting that moment (surely not far off) when their lives will take meaning from the entrance of a person they can love.

Jean Eustache’s “The Mother and the Whore” is a movie shot in Paris, but it could have been shot on just about any big American campus (and Eustache sometimes makes the Left Bank feel like an extension of that archetypal, student union up there in the sky). It is not so much about Paris as about a milieu of young people who live lives of bohemian liberation and are bored. They get drunk and sleep around and never, somehow, connect with anything that seems to make a difference.

If their lives are boring, the movie about them is not: Eustache sees through the world he is recording, he’s cynical about his characters, and he has a feel for their mode of conversation. Their talk, for the most part, is either intellectual wit or confessional self-pity. The wit tries hard (as when they speculate that Sartre’s entire philosophy is a cover-up for alcoholism, or talk about an avant-garde friend who wants to chop off his hand, encase it in plastic, and label it “My Hand–1940-1972”). But mostly what they say seems second-hand, the anecdotes of yesterday afternoon.

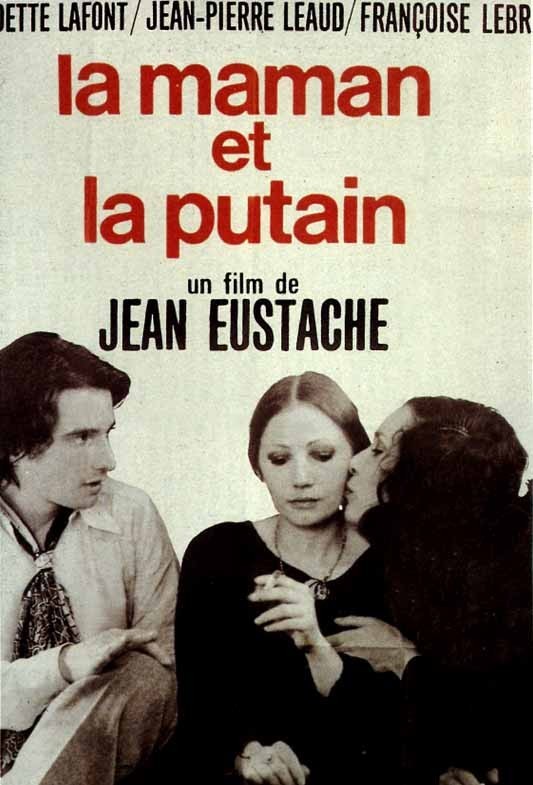

Eustache gives us three characters: Alexandre (played by Truffaut’s favorite actor, Jean-Pierre Leaud), Veronika (Francoise Lebrun) and Marie (Bernadette Lafont). They manage to form a triangle with about five sides. Alexandre’s life is set mostly in cafes. He lives with Marie, and there is some talk that they’re in love with each other, but search me. He has just been turned down by Gilberte, who he used to go with and wants to marry. Veronika looks something like Gilberte and, besides, he vowed to fall in love with the next girl he sees. He asks her out, and the rest of the movie (which is 3-1/2 hours long but not, for the most part, boring) is devoted to the games they play, the ploys they use, the confessions they make and the corners they back themselves into.

Marie is the “mother” of the title, because she represents Alexandre’s financial support and quasi-authority figure. Her boutique supports them both; he doesn’t work but spends his afternoons in the same cafe “reading–as if it were a job.” Veronika is the “whore”–not literally, but because she thinks of herself that way because she’s promiscuous. She hates herself for her promiscuity; all of the sex she’s had means nothing against the prospect of falling in love with one man and having his baby. She tells the others this in a startlingly effective monolog that’s all the more impressive when you realize Lebrun isn’t a professional actress, but just someone Eustache knew.

Alexandre cannot quite choose between the mother-figure and the whore-figure; he has got himself caught on the horns of the classical Freudian dilemma. If the movie thought his choice was all that important, it would be a disaster–but Eustache correctly sees that Alexandre’s real problem is terminal immaturity, and that the women haven’t grown up, either.

“The Mother and the Whore” is a brilliantly written film, and the performances are so good that, as I suggested, these aren’t Parisians but people we know. The movie has been attacked on the grounds that it’s Eustache’s statement on women, but that’s silly: It’s his statement on these three silly, doomed, sometimes beautiful persons.