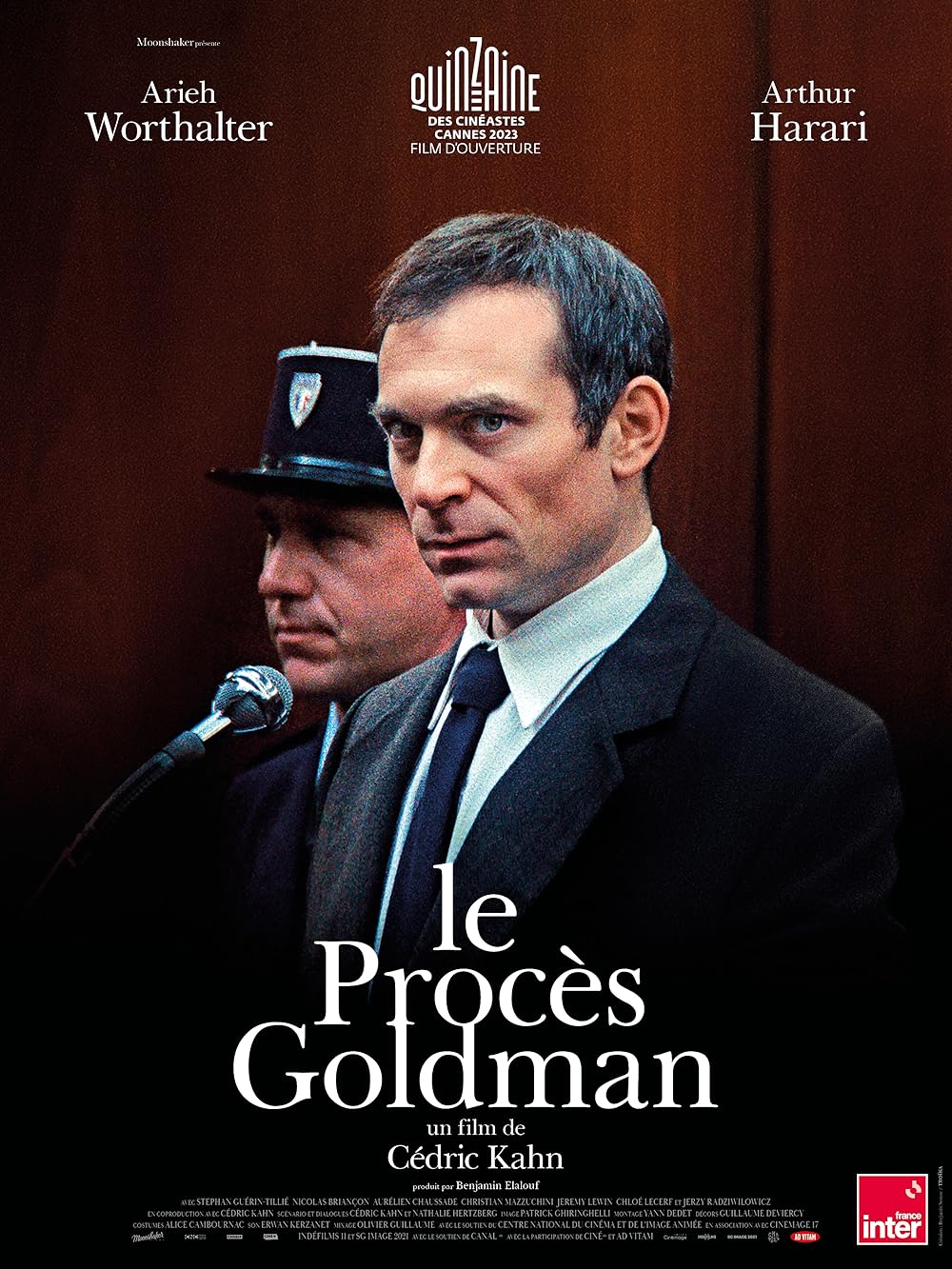

The press materials for the fact-based courtroom drama “The Goldman Case” make it clear that the filmmakers know that even the movie’s title may remind you of another high-profile case. In the email I received announcing this movie’s stateside rollout: “Twenty years before the O.J. Simpson case, the Goldman trial reflects the political, ideological, and racial tensions that marked the 1970s in France and Europe.”

While the email also said this was “considered to be the trial of the century,” the movie is less concerned with how this trial rocked the country and more with what happened inside the courtroom.

“The Goldman Case” focuses on the mid-’70s trial of Pierre Goldman (Arieh Worthalter), a French left-wing revolutionary on trial for an armed robbery and murder spree he committed in the late ‘60s. While Goldman admits to the robberies, a 1969 pharmacy attack, which led to the death of two women, is where he constantly pleads his innocence.

Goldman is definitely a fiery defendant. He often rouses the gallery, filled with young, predominantly brown-skinned people, with his declarations that this whole thing is a conspiracy assembled by a racist police force. Not only does he believe they want him locked up for being a Polish Jew, but when they arrested him, witnesses thought he looked like an Arab and “sort of mulatto.” As much as his lawyers tell him to pipe down, Goldman can’t help but raise hell. Even during his time in jail, he dropped an incendiary memoir (titled “Obscure Memories of a Polish Jew Born in France”) that the prosecution constantly references.

With most of the action taking place in a courtroom (with occasional cutaways to Goldman strategizing with his lawyers in his holding cell), viewers will most likely see “The Goldman Case” as more like a play that’s being presented in movie form. But unlike, say, Aaron Sorkin, co-writer/director Cedric Kahn makes this more of stark, no-frills, just-the-facts recreation, free of grand, dramatic flourishes and even music. It’s mainly roving, documentary-style shots of lawyers on both sides (with occasional outbursts from Goldman) breaking down statements from witnesses, whether it’s Goldman’s friends & loved ones or the people who claimed they saw Goldman that bloody night, on what’s accurate and what’s not.

“The Goldman Case” is a film where many characters generally try to keep their composure, some failing miserably. Leading this charge is Goldman, played with shit-starting vigor by Worthalter (recently awarded Best Actor at this year’s Cesar Awards for his performance). From both Kahn’s and Worthalter’s perspectives, Goldman was petulant and self-destructive, so drunk off his anti-authoritarian image that he even rebelled against his lawyers. He often butts heads with his lead counsel (Arthur Harari), who is a Polish Jew like him, but whom Goldman calls “an armchair Jew.”

Like most French courtroom dramas to hit U.S. shores in recent memory, “The Goldman Case” is less about actually solving the case and more about seeing how a guilty or innocent verdict is played out in a court of law. According to this film, a French courtroom can turn into a hermetically-sealed pressure cooker, especially when a high-profile case is being tried inside. Nearly everyone in that room, from the jury to the spectators, can speak passionately when the moment arises. It almost seems like Kahn made this movie to show how boring our court cases (and courtroom dramas) are compared to what happens across the pond.