“You gotta think about how you’ll be remembered.”

“That’s just it, Bill. Who remembers me?”

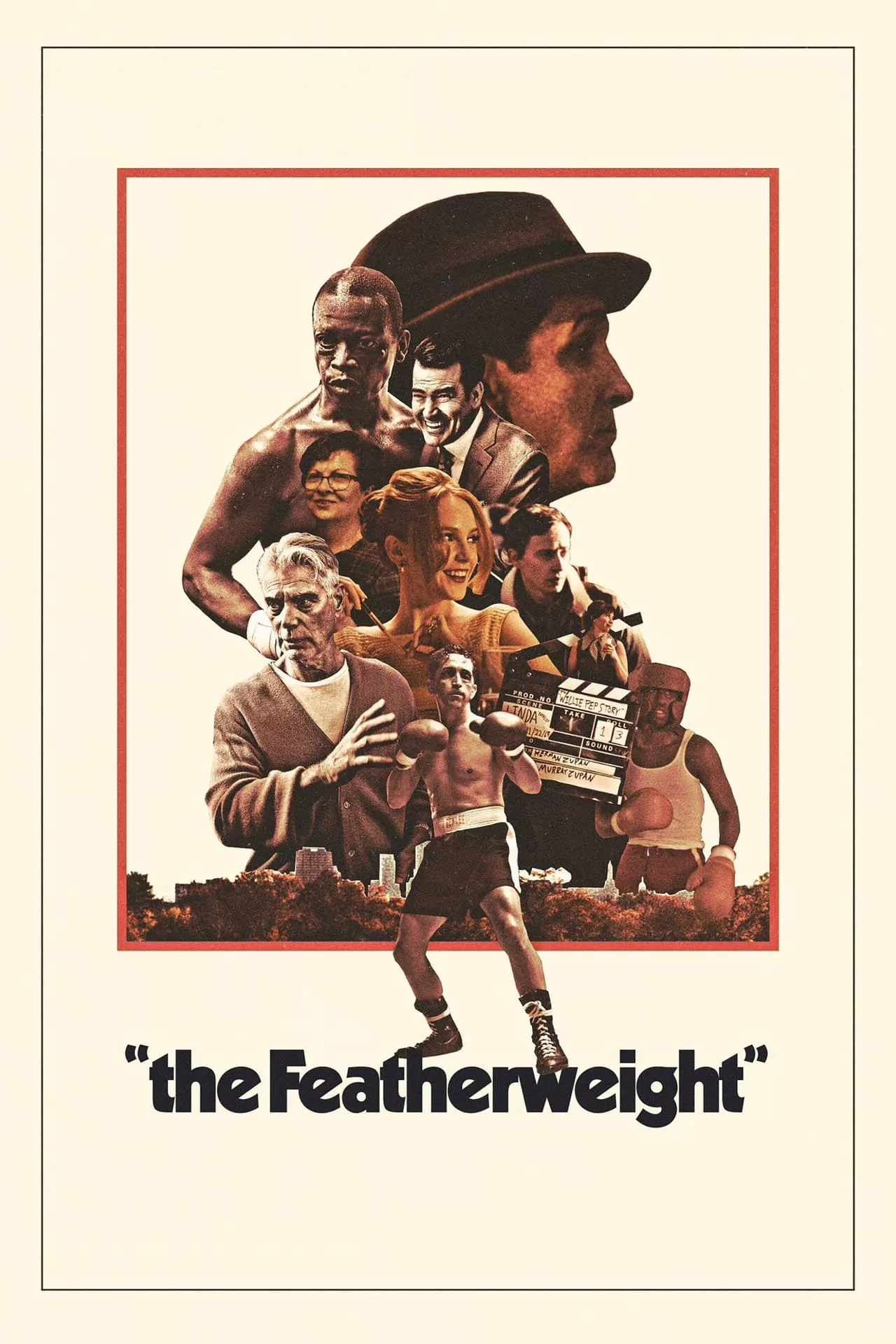

This exchange, halfway through Robert Kolodny’s nimble biopic “The Featherweight,” sums to a tee the anxieties at the center of its tragic figure. The man, of course, is two-time Featherweight world champion Willie Pep, who fought more than 230 fights in his career and won more than his fair share of them. Of course, this was in the 1940s and ’50s, as grainy newsreels show us. As we meet him here, it’s 1964, and the now 42-year-old Pep (James Madio) is looking to get back in the ring. And a camera crew is here to capture this erstwhile comeback, which turns Kolodny’s film into a hard-hitting reflection on midlife crisis and fading fame — even as it doesn’t land all of its punches.

Captured as a kind of direct-cinema documentary a la the Maysles, “The Featherweight” plants us firmly as a fly on the wall to Pep’s ambitious climb back into the ring, well past his prime. The doc, so Pep thinks, is meant to celebrate the return of an aging champion, proof positive of his bluster that he’s still got what it takes to compete. But over the next hour and a half, those same cameras merely shine a light on the fissures that exist in his personal and professional lives. That’s the compelling core of Kolodny’s film, mixing a kind of “Raging Bull” ringside character study with the probing interrogation of documentarian and subject.

Madio, a reliable character actor finally getting the kind of starmaking turn he deserves, is endearingly twitchy as Pep — a short-statured Sicilian with plenty of pride to wound. And a career of KOs, ex-wives, and the vagaries of time have certainly landed a few hits. As we meet him, he’s a little too eager to share stories of his glory days; the guys down at the coffee shop seem to like it, but his business manager (Ron Livingston) and old trainer (Stephen Lang) see it for the sad display it is. Every appearance he makes, he’s also haunted by his nemesis, Black fellow featherweight Sandy Saddler (Lawrence Gilliard Jr.), whose KO of Pep in his prime makes his parallel descent into obscurity sting all the more. Pep talks a big game about getting back in the fight, but no one wants it; the more aggressively he looks for it, the more pathetic it becomes.

It’s easy to see why he’s chasing these ghosts, though; his home life is hardly better. His third wife, a much younger woman named Linda (Ruby Wolf), is chasing her own budding acting career just as Pep’s step is losing its own pep. His mother (Imma Aiello) is your classic tight-lipped nonna, talking only in Italian around the dinner table so Linda can’t understand the insults. Then there’s Billy Jr. (Kier Gilchrist), a young man with a chip on his shoulder about Pep leaving his mom and the drug problem he can’t seem to shake. Willie Pep might as well change his last name to Loman.

Cinematographer Adam Kolodny (Robert’s brother) captures these intimate tensions in a fascinating simulacrum of period-accurate 16mm; the title designs and fonts all scream ’60s, and it’s easy to lose yourself in the documentary immediacy of the proceedings. Each scene is captured with Cassavetes-like naturalism, all frayed nerves and lived-in quirks among the ensemble. The actors were encouraged to improvise before shooting, which lends a looseness and unpredictability to their performances of Steve Loff’s screenplay. That’s then accentuated by Kolodny’s wavering camera, bobbing and weaving between actors like an expert pugilist.

But all of these tools, and all this period detail, serve a slow-burn tale of vanishing glory that feels like it’s been told before. An aging sportsman past his prime, attempting to recapture his youth as his personal life falls apart? Wake me up if you’ve heard this story before. There are also times where the narrative looseness leads to a sluggish pace, especially in the second act; we’re often left waiting for the good stuff just like Willie is. But it blissfully picks up in its third act, a one-two punch of personal tragedies that only highlight the ways Willie has failed (and been failed by) others, all in the futile search for his lost status.

Most intriguing, though, is the way Kolodny turns his characters against the camera, as they slowly realize the true cost of opening your life up to the cameras. Willie or Linda will slip up, then ask the filmmakers off-camera to “leave that part out.” (That we see it means, of course, they didn’t.) It’s an interesting wrinkle to the drama, the mere presence of the camera reflecting our characters’ selfishness and vulnerability right back at them. It’s subtly handled, a stylistic wrinkle that more than justifies the narrative-doc conceit.

“The Featherweight” elevates its been-there story of middle-aged guys chasing their glory days with some smart, unexpected performances and a genuinely intriguing aesthetic frame. It might not deliver a total knock-out punch, but it gets a few good blows in before the bell rings.