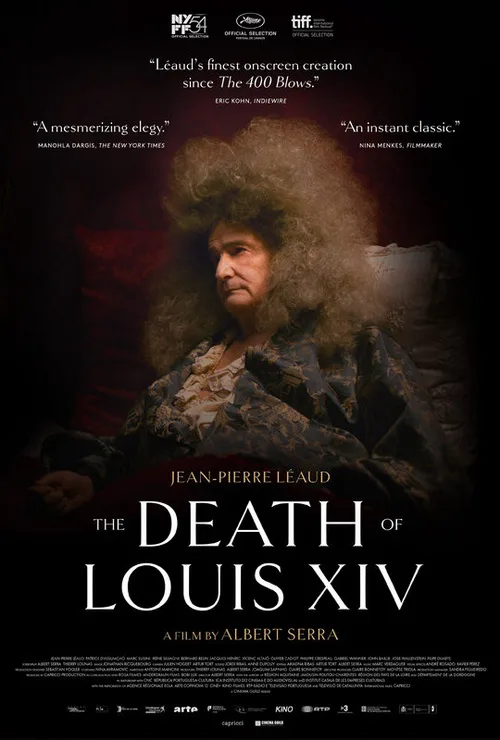

In “The Death of Louis XIV,” writer/director Albert Serra shows us that monumental events can be conveyed through the smallest of details. A series of exquisitely composed images, each one lit like an Old Master painting with the soft glow of candlelight, present us the last days in the life of one of the most powerful monarchs in modern history, Louis XIV, the man who was known as the Sun King. Most of the film consists of Louis (Jean-Pierre Léaud), under his Phil Spector-like gigantic frizzy poofs of hair, perched on his lavishly appointed bed like an enormous beached whale, as his doctors and courtiers watch anxiously and try to figure out what to do. They have to find a way to balance the deference due to the king with the imperatives of medical treatment, all while keeping in mind that an unsuccessful approach may land the doctor in the Bastille.

Aficionados of the French New Wave have watched Léaud grow up on screen, a “Boyhood”-style longitudinal study unfolding in real time. At age 14 he starred in Francois Truffaut’s semi-autobiographical “The 400 Blows.” The final scene, a close-up of Léaud’s face as he stands on the beach, is one of the most iconic images in film history. Léaud went on to star in four more films that continued the story of his “400 Blows” character, Antoine Doinel over the next 20 years. His performances in these and other movies with Truffaut, Agnes Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, and Bernardo Bertolucci have made us intimately familiar with his face as he has aged. Serra certainly selected him in part with that in mind, and the shock as we first see Léaud as a dying, very frail old man, a grand ruin, is in part because we have known him so long. The role mostly requires him to lie back on his sumptuous pillows and luxurious fabrics, but his performance is deliciously witty as he calls for his plumed hat to salute the courtiers he cannot join, insists on a crystal glass for his water, or even when he is just listening to the people around him.

Serra also mixes the very familiar with the very strange in the sickroom. Today’s physicians would recognize the way the king’s doctors confer, debating the relative merits of academic study and real-world experience. But the treatments are more like those of three centuries before Louis XIV than those of today, 300 years later. One of the king’s doctors brings a box with dozens of compartments, each with a glass eye used for diagnosis by comparison to the king’s sclera. According to his assessment, the closest match seems to suggest donkey’s milk as the appropriate treatment.

The small but wonderfully rich details of the film invite us in: the trembling of a wrinkled cheek, the arch of an eyebrow, the flicker of a candle, and especially the superbly evocative sound design. We seldom hear the kind of quiet Serra gives us in this film, no appliances buzzing and humming, no keyboards or cell phones, and, for most of the film, no musical soundtrack, just the soft murmur of the courtiers or the rustle of a page of parchment. And the film’s wry and witty last line is truly, as Louis himself might say, le mot juste.