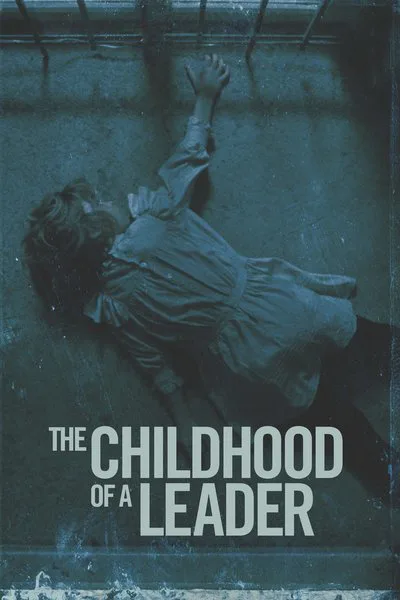

When it comes to films by twentysomething American actors making their debuts as writer-director-producers, Brady Corbet’s “Childhood of a Leader” is singular in its defiance of conventional expectations. For one thing, Corbet doesn’t give himself a role in the film. For another, its cerebral purposefulness and aesthetic audacity make “The Childhood of a Leader” almost the opposite of a Hollywood hopeful’s calling card.

Having played roles in films by Michael Haneke (“Funny Games”), Olivier Assayas (“Clouds of Sils Maria”), Bertrand Bonello (“Saint Laurent”) and Ruben Östlund (“Force Majeure”), Corbet makes his first foray into auteurist filmmaking with a movie that’s far more European than American indie in its sensibility. Beyond taking place in France, it also bites off a particularly potent slice of European history to chew on: the time of the Treaty of Versailles, when one world war was being laid to rest even as the conditions for the next were being fashioned.

The film announces that historical setting with an initial barrage of newsreel images that are all the more riveting when set to pop innovator Scott Walker’s propulsive, clangorous score, which is an asset throughout. Once the story properly begins, it seems to be in a haven from the conflict that so recently tore the continent apart. In a peaceful French village, children in costumes are preparing for a Yule pageant (this is Christmas 1918). Among them is a long-haired little boy who soon exits the gathering, and, for reasons not apparent, begins hurling stones at the others.

A title identifies this section of the film as “Tantrum Number One”—the first of three tantrums which organize the narrative. The perpetrator of all three is the little boy of the first scene, who belongs to the family of an American diplomat (played by Irish actor Liam Cunningham) in France for the post-war negotiations (which began in January, 1919). He is a married to a German-born woman (Bérénice Bejo), who undertakes the task of punishing the child and making him own up to his malefactions.

Very late in the film, we hear the child referred to by name once: Prescott. (His parents are never named.) The boy’s identity thus is something of a mystery throughout, one that the film’s title invites us to ponder from the get-go. Which leader’s childhood are we witnessing? Is he a historical person or a fictional/symbolic construct?

This review will not reveal answers or possible answers to the mysteries the film poses, but rather will note that much about Corbet’s creation is mysterious, opaque, oblique—an approach that’s bound to leave viewers divided. Some may want more clarity on all fronts: who the characters are, the nature of their inter-familial problems and the implied connection of their domestic drama to the great drama of negotiations that will occupy Europe for the next six months. Those who allow Corbet’s tale to establish its own cinematic logic, on the other hand, will end up relishing the very original way he skirts countless conventions in recurrently casting the task of meaning-making back on the viewer.

Much of this is done by glimpsing the central family almost as a servant or visitor would. Little Prescott is willful and headstrong, almost to an obnoxious extent, yet he seems no more disturbed or destructive than any typical upper-class only son of that era. His parents occupy their own discrete worlds within the family home, the mother organizing servants and teachers, the father discussing politics with a visitor (Robert Pattinson, who plays two roles in the film). The grown-ups converge only seldom to confer on the care and discipline of the boy, who may be at the center of their concerns yet whose actions never provoke an out-and-out crisis.

The fact that the film proceeds from minor incident to minor incident without attempting a typical dramatic architecture or drive is one of its riskiest conceits. Corbet allows the details to accrue at an unhurried pace, and the pay-off is that we are drawn into this distant world as we would be if we came to know the family over a period of time. Interestingly, this is done without our being encouraged to identify with any of the main characters; we get close to them even while continuing to observe them from a distance.

The film’s visual approach makes the most of this observational stance. With its elegant Vermeer lighting, cinematographer Lol Crawley renders the family’s house as a character with its own moods and secrets, ones evoked through oblique camera angles and shots that linger pensively on shadowy rooms well after people have left them.

A young British actor named Tom Sweet occupies the center of this crepuscular environment with an almost preternatural presence as Prescott. With his golden locks and foppish Little Lord Fauntleroy wardrobe, Prescott is sometimes mistaken for a girl, which increases his rages, but there’s nothing unclear about Sweet’s performance. A truly remarkable piece of work by an actor so young, it impressively anchors a film where all of the acting is solid and evocative.

The script that Corbet wrote with Mona Fastvold is reportedly based on a 1939 piece of the same title by Jean-Paul Sartre, and its central idea has been understood as positing a certain psychological background for fascist leaders. But if anyone looks to Corbet’s film for a rigorous working-out of that notion, they’re bound to emerge disappointed. More than anything, the movie plays as a personal, poetic look back at a century where history, cinema, psychology and politics intersected in ways that we are still trying to parse. That it has the courage of cryptic-ness, and leaves sympathetic viewers intrigued long after its final images have faded, is enough to mark “The Childhood of a Leader” as an uncommonly promising debut.