The detective in “The Caveman’s Valentine” is a raving lunatic on his bad days, and a homeless man on a harmless errand on his good ones. Once he was a brilliant pianist, a student at Juilliard. Now he lives in a cave in a park. His dreadlocks reach down to his waist and his eyes peer out at a fearsome world. You’d be fearful, too, if your enemy lived at the top of the Chrysler Building and attacked you with deadly rays.

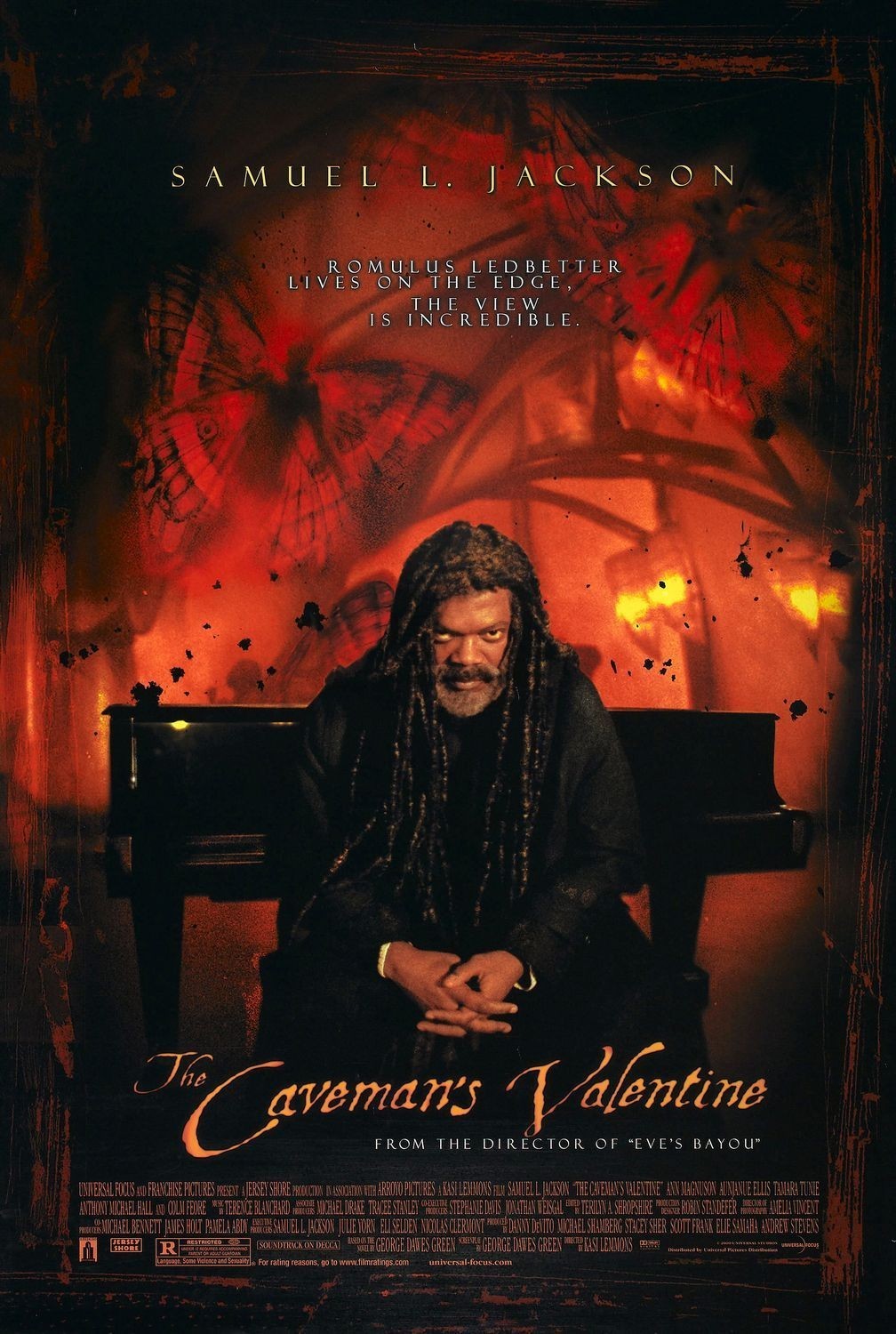

Romulus Ledbetter is one of Samuel L. Jackson‘s most intriguing creations, a schizophrenic with sudden sharp stabs of lucid thought and logical behavior, whose life is changed one day when the frozen body of a young man is found outside his cave in a city park. The police believe the man, a transient, froze to death. Romulus thinks he knows better, and his desire to unmask the real killer draws him out of his cave into a daring foray into the New York art world.

Romulus is not without connections. His daughter Lulu (Aunjanue Ellis) is a policewoman. But she is hardly convinced by his first suspect: his enemy in the Chrysler Building. By the time he discards that hypothesis and zeroes in on a fashionable photographer named Leppenraub (Colm Feore), it’s too late for anyone to take him seriously–if they ever could have in the first place.

The challenge for Jackson and his director, Kasi Lemmons, is to make Romulus believable both as the caveman and as a man capable of solving a murder. Too much ranting and raving, and Romulus would repel the audience. Too much logic, and we don’t buy him as mentally ill. Even the clothes and the remarkable hair have to be considered; this is not a man you would want to sit next to during a three-day bus trip, but neither does he tilt over into repellent grunge (like the aliens in “Battlefield Earth“). It’s remarkable the way Jackson begins with the kind of character we’d avert our eyes from, and makes him fascinating and even likable.

This is Lemmons’ second film; after her remarkable debut, “Eve's Bayou” (1997), she repeats her accomplishment in fleshing out a story with intriguing supporting characters. Chief among these is Leppenraub, a gay photographer who savors sadomasochistic imagery, and his employee-lover Joey (Jay Rodan), who makes digital videos. If Leppenraub killed the dead young man, did Joey film it? Romulus is able to enter the photographer’s world through an unlikely route, involving a bankruptcy lawyer who befriends him, cleans him up and enlists him as a pianist for a party. At one of Leppenraub’s openings, the dreadlocked caveman looks at the photographs with the clear eye of the mad but logical, and says exactly what he thinks.

Is this a reach, suggesting that the caveman and the photographer could find themselves in the same circles? Not in the art world, where unlikely alliances are forged every day; the movie “Basquiat” is about an artist who made the round trip from the streets to the galleries. It’s also plausible, if unlikely, that the cleaned-up Romulus, an exciting man with an electric presence, could attract the sexual attention of Leppenraub’s sister Moira (Ann Magnuson), who seduces him because she likes to shock, she likes to try new things and she likes the guy (of course, she doesn’t know his whole story).

The actual solution to the murder mystery was, for me, the least interesting part of the movie. “The Caveman’s Valentine” is based on a crime novel by George Dawes Green, who also wrote the screenplay, and like many procedurals it has great respect for clues, sudden insights, logical reasoning, holes in stories and all the beloved devices of the detection genre. At the end all is settled and solved, but I agree with Edmund Wilson in his famous essay on detective novels when he concluded, essentially, “so what?” The solution simply allows the story to end. The engine that makes the story live is in the life of Romulus: in how he survives, how he thinks, how people see in him what they are looking for. To watch Samuel L. Jackson in the role is to realize again what a gifted actor he is, how skilled at finding the right way to play a character who, in other hands, might be unplayable. I think the key to the whole performance is in Romulus’ walk. It’s busy and bustling, as if he’s late for an appointment that he’s rather looking forward to. He seems absorbed in his thoughts and plans, a busy man, with the jam-packed calendar of the mad.