“Battlefield Earth” is like taking a bus trip with someone who has needed a bath for a long time. It’s not merely bad; it’s unpleasant in a hostile way. The visuals are grubby and drab. The characters are unkempt and have rotten teeth. Breathing tubes hang from their noses like ropes of snot. The soundtrack sounds like the boom mike is being slammed against the inside of a 55-gallon drum. The plot. . . .

But let me catch my breath. This movie is awful in so many different ways. Even the opening titles are cheesy. Sci-fi epics usually begin with a stab at impressive titles, but this one just displays green letters on the screen in a type font that came with my Macintosh. Then the movie’s subtitle unscrolls from left to right in the kind of “effect” you see in home movies.

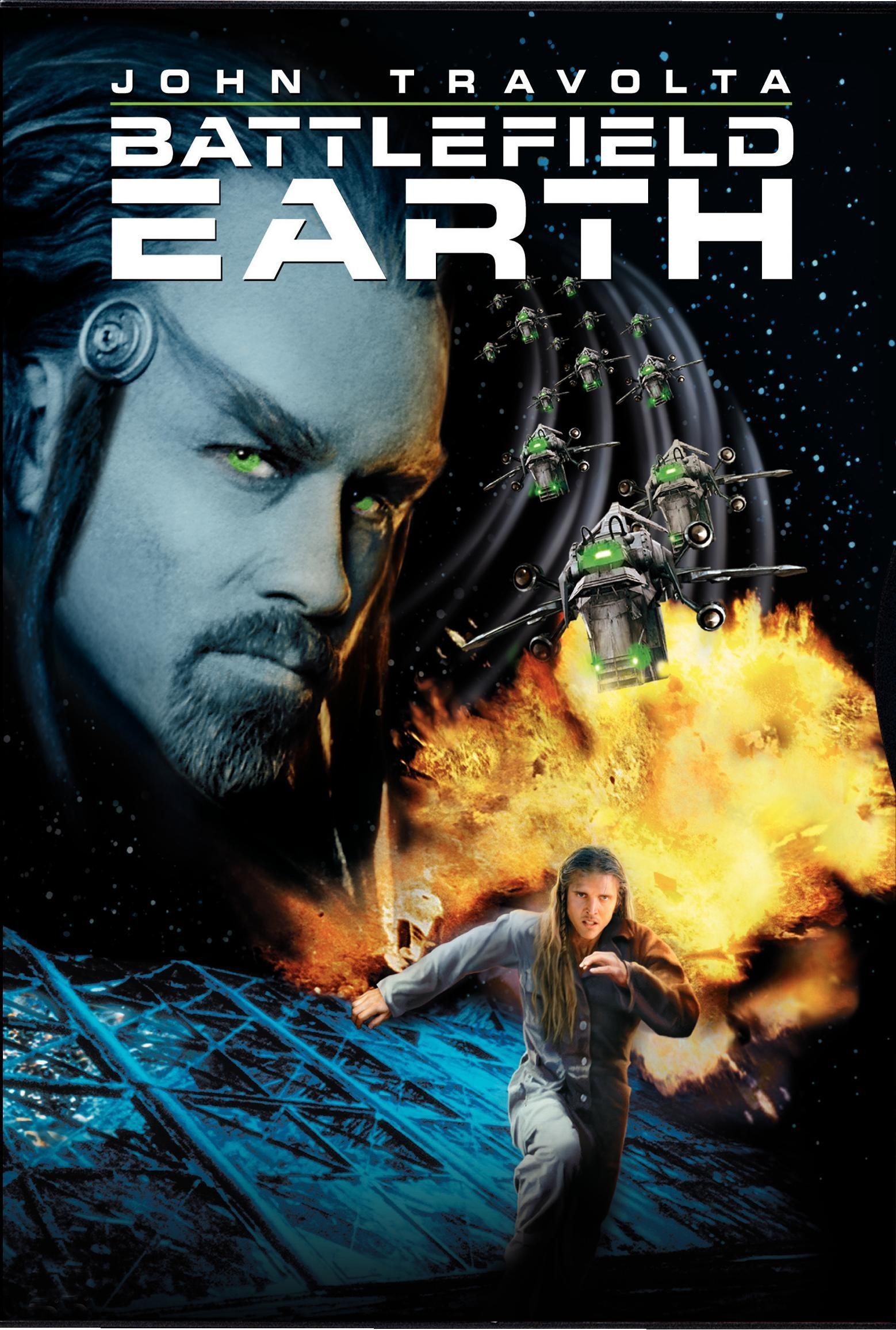

It is the year 3000. The race of Psychlos has conquered the earth. Humans survive in scattered bands, living like actors auditioning for the sequel to “Quest for Fire.” Soon they leave the wilderness and prowl through the ruins of theme parks and the city of Denver. The ruins have held up well after 1,000 years. (Library books are dusty but readable, and a flight simulator still works, although where it gets the electricity is a mystery.) The hero, named Jonnie Goodboy Tyler, is played by Barry Pepper as a smart human who gets smarter, thanks to a Pyschlo gizmo that zaps his eyeballs with knowledge. He learns Euclidean geometry and how to fly a jet, and proves to be a quick learner for a caveman. The villains are two Psychlos named Terl (John Travolta) and Ker (Forest Whitaker). Terl is head of security for the Psychlos and has a secret scheme to use the humans as slaves to mine gold for him. He can’t be reported to his superiors because (I am not making this up) he can blackmail his enemies with secret recordings that, in the event of his death, “would go straight to the home office!” Letterman fans laugh at that line; did the filmmakers know it was funny? Jonnie Goodboy figures out a way to avoid slave labor in the gold mines. He and his men simply go to Fort Knox, break in and steal gold. Of course it’s been waiting there for 1,000 years. What Terl says when his slaves hand him smelted bars of gold is beyond explanation. For stunning displays of stupidity, Terl takes the cake; as chief of security for the conquering aliens, he doesn’t even know what humans eat, and devises an experiment: “Let it think it has escaped! We can sit back and watch it choose its food.” Bad luck for the starving humans that they capture a rat. An experiment like that, you pray for a chicken.

Hiring Travolta and Whitaker was a waste of money, since we can’t recognize them behind pounds of matted hair and gnarly makeup. Their costumes look like they were purchased from the Goodwill store on the planet Tatooine. Travolta can be charming, funny, touching and brave in his best roles; why disguise him as a smelly alien creep? The Psychlos can fly between galaxies, but look at their nails: Their civilization has mastered the hyperdrive but not the manicure.

I am not against unclean characters on principle–at least now that the threat of Smell-O-Vision no longer hangs over our heads. Lots of great movies have squalid heroes. But when the characters seem noxious on principle, we wonder if the art and costume departments were allowed to run wild.

“Battlefield Earth” was written in 1980 by L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology. The film contains no evidence of Scientology or any other system of thought; it is shapeless and senseless, without a compelling plot or characters we care for in the slightest. The director, Roger Christian, has learned from better films that directors sometimes tilt their cameras, but he has not learned why.

Some movies run off the rails. This one is like the train crash in “The Fugitive.” I watched it in mounting gloom, realizing I was witnessing something historic, a film that for decades to come will be the punch line of jokes about bad movies. There is a moment here when the Psychlos’ entire planet (home office and all) is blown to smithereens, without the slightest impact on any member of the audience (or, for that matter, the cast). If the film had been destroyed in a similar cataclysm, there might have been a standing ovation.